Archive for the ‘Economy’ Category

And yet more on housing

Twice burned, you know? I think we should all be a bit gun-shy about rapidly increasing house prices. Are we looking for a bubble or a peak?

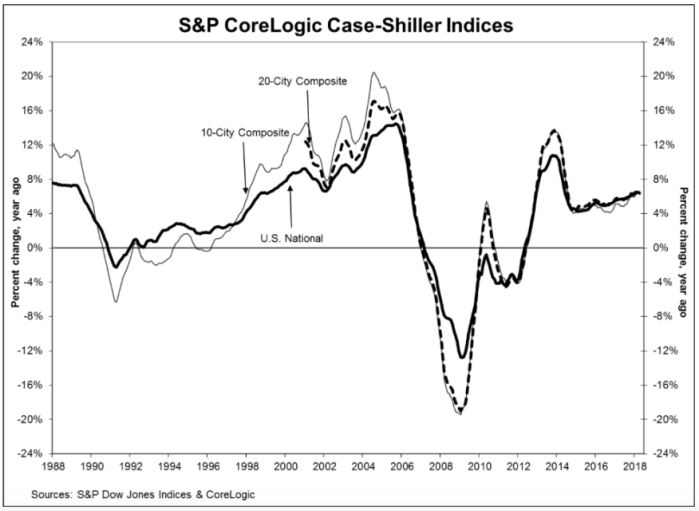

The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index, reported a 6.4% annual gain in April, slightly down from an annualized rate of 6.5% in March. While they produce a few other indices, all of them basically report the same thing. Oh, by the way, my home city of Seattle leads the pack with an annualized rate north of 13%.

Glancing at the graphic, below, the slope of the current pricing graph looks suspiciously like what we saw during the bubble run-up. As I’ve noted here previously, house prices increasing at a rate higher than 2 points over inflation is emblematic of a bubble. That would suggest a nationwide rate somewhere around 4% – 5% right now. You do the math.

Deconstructing house prices

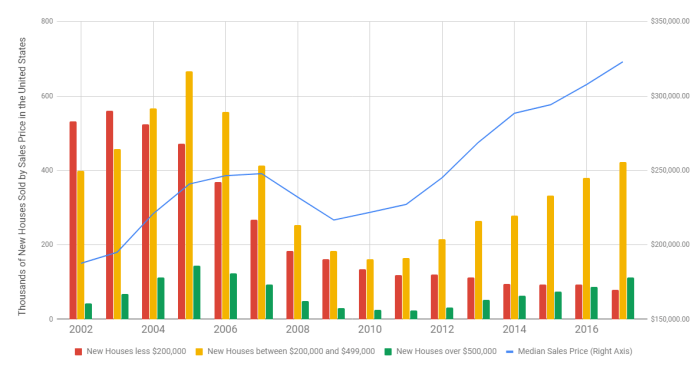

I stumbled on a very interesting graphic on the inter-web the other day. I can’t provide the citation just yet — it was posted anonymously on a data visualization web site. Nonetheless, I’ve done a bit of research to semi-validate these numbers, and even if they’re off a bit, it’s a very useful graphic.

First, it tells us that since 2002, the median price of a new home in America has approximately doubled, from $175,000 to about $350,000 (depending on exactly which metrics you use, this is about right). That’s an inflation rate of about 100%, more or less, in 15 years (end of 2002 to end of 2017). In a paper I presented at the American Real Estate Society annual meetings about 10 years ago, I noted that post-WW2 data indicated that house prices/values should be expected to grow annually at a rate of about 2 percent points above the inflation rate. I checked, and the actual inflation rate over that period measured by the CPI totaled 36%, more or less. That averages about 2.1% per year, compounded. The doubling of house prices in 15 years equates to an inflation rate of about 4.7%. So…. 4.7 minus 2.1 = 2.6. Thus, by my estimation based on historical averages, house prices have been growing about 0.6% per year faster than they should have since 2002.

You might argue that some of that was the last few years of the housing bubble, but that sponge got squeezed out in the post-bubble collapse. Nope, folks, what we’re seeing is the echo bubble. You might also argue that 0.6% doesn’t sound like much, but here’s what it amounts to over time. If house prices had actually grown at the rate suggested by previous post-WW2 data, then prices would only have gone up by about 170% over that time period. That means that a $175,000 house from 2002 should today be selling for about $295,000. The difference (350,000 minus 295,000) of about 17% is the measure of the echo bubble — it’s the degree to which houses are currently overpriced.

Ahem…. that’s NOT the point of this story. That’s just the introduction. The more important story comes from deconstructing house prices into various tranches. This graphic I found does a wonderful job of that:

Here’s my point in a nutshell. Note that in 2002, the plurality of homes built were in the “less than $200,000” category. Today, that’s the smallest category (the one in red). Conversely, we’re building about twice as many homes in the expensive category (the green bar) as we were in 2002. While all housing starts are down from the peak, compared to the earlier years, we’re now building the bulk of the housing in the two most expensive categories, which is a real shift from 2002.

Why? The market is constantly screaming about the lack of supply for “affordable housing”. Why aren’t builders building to that tranche of the market? The answer is cost. Two very disruptive forces are plaguing the homebuilding industry today. First, the labor and infrastructure for building died off during the recession. We have relatively fewer trained and skilled tradespeople, fewer developed lots (and a shrunken pipeline for development) and more expensive construction lending. Second, the building materials themselves — lumber and steel — are in short supply, have been affected by price increases, and are now faced with tariffs. Builders have no choice but to build more expensive homes to be able to cover the cost of construction.

Are we headed for a new bubble? Back in the dark ages, when I was in graduate school, we were taught that inflation could be caused by either demand-pull (too much money chasing too few goods) or cost-push (increases in commodity costs). Either way you look at it, the cost of owner-occupied housing is going thru the roof (pun intended).

A quiet Sunday

Tariffs are back in the news. Do I REALLY have to comment on why this is a bad idea?

First, go read about the Law of Comparative Advantage. It’s nearly as old as the study of economics itself. It explains why a society is better off with unfettered trading. Admittedly, there are micro-dislocations. A worker who was skilled at making stuff may need to learn to make other stuff. However, the best and quickest way to kill an economy is to start a trade or tariff war. The Smoot Hartley Tariff Act of 1930 is universally recognized as deepening the Great Depression. Anyone who is in favor of tariffs was apparently laying out with a hangover the day they taught that in Econ 101.

Boring stuff for a Sunday morning

Any reasonably good education in finance or economics will include a discussion of the term structure of interest rates. It’s important to understand — in normal times, short term rates (both borrowing and lending) are lower than long term rates. However, these rates move all over the map, and at times the relationship can be inverted, as it was back in 2000 (see below).

(By Farcaster – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66130747)

Why do these rates move around so much, and how can they become inverted (yes, that IS illogical)? Ahhh…. that’s important, but still terribly boring. In general, there are three theories — market expectations, market segmentation, and liquidity preference. Today, I’m interested in the third. In short, in times of trouble, investors (that’s you and me, by the way) want to stay liquid. As such, shorter term rates are artificially pushed down and longer term rates pushed up. The 2011 experience is an example.

So why is this of interest (pun intended) on a boring Sunday morning? Because I made the mistake of reading the news this morning, and happened upon a story from Quentin Fottrell of Marketwatch.com, reprinted in Yahoo Finance (yes, THEY’RE still around!) titled “Americans are hoarding money in their checking accounts — and that could be a problem.” In short, yes it could. To quote, “When times are good, Americans feel confident by keeping little in checking, but when times are difficult consumers store money in checking accounts, effectively pulling back on spending on retail and restaurants.” It’s an excellent article, and I highly recommend it.

Collapsing Price of Alternative Energy

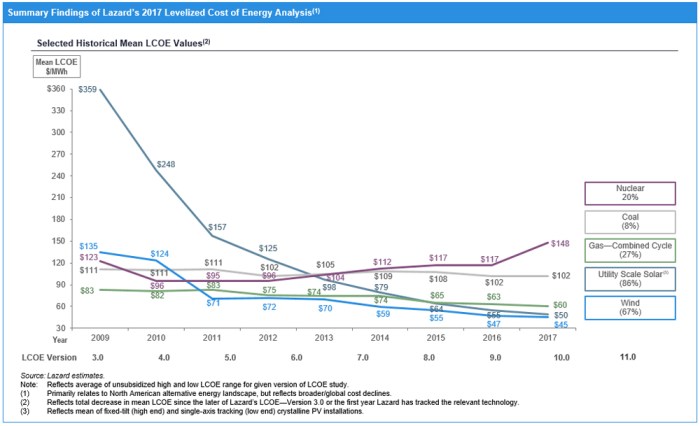

Most — nearly all — of our work is in real estate, but energy has a huge real estate component, so major shifts in the energy market have significant implications for real estate investment.

A recent report out of Lazard reflects just such a major shift. Specifically, among five major sources of energy, wind and solar are now the low-cost alternatives. Indeed, since 2009. the cost of solar energy (at a utility scale — not just what’s on the roof of your house) has declined by 86% to about $50 per megawatt hour. Coal, for example, has declined in price only 8% during that period, and is now $102/MWh, or double the cost of solar. Wind is even cheaper, at $45/MWh.

Thanks to Lazard for the accompanying graphic.

The implications for real estate are obvious. If and as utilities shift supply sources, and focus on alternative energy to meet increasing demands, there will be an accompanying demand for solar farms, wind farms, and new transmission lines. Accompanying this, we’ll probably see a decreased utilization of coal mines, and certainly a reduced demand for new coal mines.

Commercial Real Estate — Prices vs Values

Anyone involved in real estate knows that commercial prices and values have been on a constant uptick since the trough following the recession. The very length and breadth of the recovery has caused nervousness among investors, appraisers, and lenders. Today, I’m looking at two somewhat disparate views on the subject.

First, Calvin Schnure, writing for NAREIT, looks at four measures of valuation:

- Cap rates and cap rate spreads to Treasury yields

- Price gains, either from increasing NOI or decreasing cap rates

- Economic fundamentals, such as occupancy and demand growth

- Leverage and debt growth

At present, none of these is giving off warning signals, according to Schnure. Cap rates continue to be low compared to other cycles, but so are yields across the board. There continues to be room for cap rate compression, in Schnure’s assessment. As for price changes, every sector is showing growing or at least stable NOI, with the proportion of price changes coming from NOI now equal or exceeding price increases coming from cap rate declines. Across the board, REIT occupancy rates are high and on the rise, with industrial and (surprisingly) retail at or near 95%. All equity REITs are in the low 90% range, compared to the high 80’s at the trough of the recession. Finally, debt levels are rising, but at a lower rate than valuations. Ergo, this is not, in his opinion, a debt-fueled cycle. Right now, debt/book ratios are significantly lower than in the previous FOMC tightening cycle (2004-2006). For a full copy of Schnure’s article, click here.

Second, I was at the American Real Estate Society’s annual meeting in Ft. Myers, FL, last week, and had the great pleasure to sit in on a presentation by my good friend Dr. Glenn Mueller of Denver University, the author of the widely acclaimed Market Cycle Monitor. He tracks property types and geographic markets by occupancy, absorption, and new supply statistics, and for years has proffered a very accurate measure of commercial real estate, both nationally and locally, across four potential phases:

- Recovery (rising, although unprofitable rents and occupancy)

- Expansion (rising and profitable rents and occupancy, stimulating new construction)

- Hypersupply (oversupply of new construction and declining rents and occupancy)

- Recession (unprofitable and declining rents and occupancy)

Most markets cycle through these phases in a fairly predictable fashion. Right now, most markets (property types and geography markets) appear to be in the expansion mode, with some (notably, apartments) potentially crossing the line into hypersupply.

In short, commercial real estate markets look healthy, absent the sort of exogenous shocks that sent us into the most recent recession. That said, many of those same metrics read positive prior to the mortgage market melt-down. Of course, commercial real estate actually faired pretty well during the recession, compared to many other asset classes, supporting the notion that in times of economic trouble, real estate equities can be great storers of value.

An important story on trade

Alexis Crow, who leads the geopolitical investing practice at Price Waterhouse Coopers, has a stunningly important article on trade in today’s Washington Post. I recommend you read it here. In short, Trump’s trade war misses a very important point — the U.S. economy has matured from manufactured goods to services, and actually runs a net surplus of such services to the rest of the world.

As she notes, “Providing services is the heartbeat of America’s new economic growth, including IT and communications services, logistics, warehousing, leisure, hospitality, health care, business and legal services.“. She goes on to note that wealth created by America’s trading partners — China, Japan, etc. — translates into purchase of American services, including travel, media, IT, logistics, and entertainment. By 2026, fully 81% of American jobs will be in such service areas, and our trade surplus in these areas is already nearly $300 Billion per year.

Damage to Reputation/Brand

In my last post, I commented about AON’s Global Risk Management Survey. I want to continue on that theme today, and continue to compliment the great folks at AON for a super job.

Number one on their list was Damage to Reputation / Brand. The open the chapter on that with a wonderful story, which I will briefly retell here (with full attribution). A worker in China purchased an electronic device and while charging it, the device caught fire. He videotaped the incident and uploaded it to the internet. The clip was soon viewed millions of times around the world. Other customers reported similar defects. Even though less than 0.1% of the devices sold were defected, widespread panic followed. the company was forced to issue a world-wide global recall costing an estimated $5 Billion. Ironically, this tech company became a victim of the tech revolution.

AON notes that widespread fake news, the lack of fact checkers on social media, and the political cross-fire following the US 2016 elections all have risk for brand damage. AON estimates that there is an 80% chance a company could lose at least 20% of its equity value in a month over a 5 year period doe to a reputation crisis.

Eight years earlier (2009), Damage to Brand / Reputation was ranked number 6 among risks by respondents. Today it is number one. Reputation / Brand events often arrive with little or no warning, to cite the survey, and organizations are forced to respond quickiily. As such, it is critical that companies have comprehensive reputation risk control strategies in place. Such strategies include meticulous preparation and executive training, to help maximize the probability of recovery.

Thanks again to the good folks at AON for providing this information.

AON’s Global Risk Management Survey

The good folks at AON just shared with me their very detailed Global Risk Management survey for year-end 2017. It’s a terrific document, very thoroughly researched, and I commend them for the effort they put into this. (Full disclosure – neither I nor Greenfield, nor any of its affiliates, have any interest in AON.). This is the sort of study that should be on the desk of every CEO who has globally-affected interests, and certainly real estate and private equity fall into that category.

The document is chock-full of good stuff, and I’ll revisit this in future posts. Two interesting comments, however, hit me right up front. First, and I’ll simply quote from the survey, “…developed nations, which were traditionally associated with political stability, are becoming new sources of volatility and uncertainty that worry businesses…”. Of course, they’re taking about the U.S. and its misguided trade war, BREXIT, the elections in Northern Europe, and the impeachment of the South Korean president.

Second, what are the top concerns for global businesses and wealthy families? The list may come as a surprise to those who don’t follow these important sectors, but these certainly make sense in today’s climate:

- Damage to reputation/brand

- Economic slowdown / slow recovery

- Increasing competition

- Regulatory / legislative changes

- Cyber crime / hacking / viruses / malicious codes

- Failure to innovate / meet customer needs

- Failure to attract or retain top talent

- Business interruption

- Political risk / uncertainties

- Third party liability

I can tell you Greenfield is deadly serious about these issues. You should be, too.

NYC Family Office Club

I had the very real pleasure of attending the Family Office summit in New York City last Friday. The meeting drew together about 400 individuals, give or take, who are involved in various aspects of management or advice to family offices. Greenfield was, of course, the one of the leading real estate advisory providers there.

For the uninitiated, a Family Office is more-or-less what it sounds like. A family views its financial and other holdings as something to be managed for the benefit of the entire multi-generation family. A very, very rough division might categorized those families with a billion dollars of net worth or more, families with $100 million to a billion, and families with aggregate net worth below $100 million. For the first category, the family office is usually a separate business enterprise managing just that family. It may directly employ one or more attorneys, accountants, and investment advisors, or at the lower end of the scale perhaps just one or two professional managers with other professionals on retainer. The family office manager ensures that the assets are well invested and well managed, that the taxes and other bills get paid on time, and that the family estate is managed.

In the middle category, a professional manager may oversee several families, or in some cases a management team may oversee a dozen or more families. The suite of services is somewhat less (estate management and day-to-day bill paying may not be on the table). At the lower end, for families with $50 to $100 million in investable net worth, there are trust companies that manage the money and make sure the tax accountant gets everything needed.

It goes without saying that above a certain level, every wealthy family has some sort of family office. To quantify this, the wealthiest 0.1% (that is, one tenth of one percent) of American families have an average net worth of $200 million. Ahem… That’s 125,000 families. It perhaps goes without saying that these families are shown the best investments, receive the best legal, accounting, and advisory services, and expect mind-boggling results.

Now, you’d think that the lessons learned from these uber-wealthy families and their advisors would have little to do with the average American family, but indeed that’s far from the truth. Amazingly enough, the lessons learned here are applicable to every family in America, indeed the world. I’ll summarize just a few.

- The family matters more than the money. Indeed, the wealthy families I’ve spoken with manage their money carefully and purposefully to knit together the family across generations. Even so, only 30% of earned wealth hangs around past the third generation. Why? The biggest single issue was family disputes.

- There is an extraordinary global industry of lawyers and others devoted to family reputational management. Managing a family’s reputation is paramount.

- Most wealth families expect their investment advisors to preserve wealth. They already know how to make money, they just don’t want their advisors to lose it. That said, they don’t like blind pools, they want to be in control of private equity investments (but are open to partnering with other families or “sidecar” arrangements) and prefer private equity to public.

- Wealthy families and their investment managers are rarely open to an investment “pitch”. They want to get to know an investment manager first, and may not be open to an investment until the third or fourth idea.

There were a lot of other details, and I’ll leave those for another time.