Archive for the ‘Finance’ Category

And yet another post about housing

With all the negative news about housing, the market may have a tendency to grasp at any straw that floats along. In today’s news, that straw is a report from the census bureau that home ownership rates — which have been declining steadily for two years, and are now at a 13-year low — seemed to reverse trend in the 3rd quarter and rise by 0.4% to 66.3%.

Of course, a quick read of the footnotes belies the problem with this pronouncement. First, as you can see, there’s a fair amount of cycling around long-term trends, and that’s probably what this is. Second, on a seasonally adjusted basis (which is really where the truth can be found), the increase was only 0.2%, which is statistically insignificant. Further, on a year-to-year basis, we’re still lower than where we were a year ago, which really underscores the long-term trend. I continue to believe that ownership rates will stabilize somewhere above 64%, but probably pretty close to it. At the current trend, that may take 3 – 5 years.

More importantly, though, an increase in housing demand (and prices) led us out of prior recessions, but housing is continuing to be a drag on the market following this most recent one. Unless and until the housing market doldrums stabilize, solid economic growth will elude us.

Housing redux

While I’m on the subject, the Royal Instition of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), of which I’m a Fellow, publishes a great . Last week’s edition had a piece on the U.S. housing market doldrums, with a particular emphasis on the dearth of mortgage purchases (the secondary market which is vital to the liquidity of the mortgage business).

As you might guess, this important segment of the market peaked in 2005/6, and with a brief attempt at pick-up in early 2008, has been on a downward slide ever since. The index currently stands more than 60% down from the peaks of just 5 years ago. The trend continues downward, and fell 3.5% in the third quarter of this year.

They note that residential investment as a percentage of GDP currently stands at 2.2%, down from pre-recession levels of 6.6%. What’s more, the excess supply overhang will take years to absorb, according to their analysis.

The health — or lack thereof — us currently a front-burner issue for the Federal Reserve, which is now looking at the mortgage bond market as a means of helping to stimulate this anemic sector. Both FRB member Daniel Turillo and Vice Chair Janet Yellen have made public pronouncements in that direction recently.

CNBC reports on housing doldrums

Diana Olick is the real estate blogger/reporter for CNBC, and has a great column this week commenting on the recent “semi-good-news” from CoreLogic. For her full column, and links to the CoreLogic report, click here.

The synopsis — CoreLogic reports that foreclosure sales as a percentage of total sales are down. Great news, if it wasn’t for the sad fact that distress sales in May were still at 31% of the total market, albeit down from 37% in April.

Ms. Olick correctly notes that the “shadow” market hanging out there is huge. A few snippits:

Loans in the foreclosure process (either REOs or in-process) total 1.7 million homes, down from 1.9 million a year ago. Given that total home sales in America seem to be hovering around 5 million per year, this is a huge portion of the inventory.

The Livingston Survey — Semi-Good News

Regular readers of this blog will note that I’m enamored with the Philadelphia FED’s surveys of professional economists. They actually do two surveys — one quarterly series, which has a slightly larger survey base, but doesn’t go into as much depth; and the semi-annual Livingston Survey, which has a smaller audience but a lot of detail. For direct access to the current Livingston Survey, click here.

Bottom line? The first half of 2011 isn’t as rosy as economists previously predicted, but they’re still modestly bullish on the second half of the year. Currently, the annualized GDP estimate is an anemic 2.2%, down from an almost-equally boring 2.5% in the December survey. However, GDP growth in the second half of the year is expected to be even stronger than previously thought, with second-half growth forecasted at an annual rate of 3.2%. More significantly, previous estimates of unemployment are being cut. In the last survey, economists collectively projected that year-end 2011 unemployment would stand at 9.2%; today, that projection has been lowered to 8.6%. Of course, these projections were surveyed before the most recent nasty jobs-growth reports, so everyone who uses this data is taking a bit of a “wait and see” prospective.

The nasty news is on the inflation front — prior estimates put the consumer price index rise from 2010 to 2011 at 1.6%; current consensus thinking is 3.1%. While that doesn’t sound like much, the producer price index is even worse — a prior estimate of 1.9% is now being revised to 6.3%. Both indices are expected to settle down in 2012, but we can only hope.

With that in mind, projections of T-Bill and T-Note rates are, not unexpectedly, higher than previously thought. The current 3-month T-Bill rate (as of this morning) is 0.04%. Current thinking is that we will end June in the range of 0.08%, but that by the end of 2012, 3-month bill rates will be up to 1.58%. Ten-year Note rates will follow a similar, but slightly flatter pattern (representing a slight expected flattening in the yield curve). The 10-year composit Note rate as of this morning (according to the Treasury Department) was 3.77%. Economists actually project it will decline a bit by month-end (to 3.25%), then rise slightly by the end of 2012 to 4.5%.

A Movie Review of Sorts

I just saw HBO’s “Too Big To Fail”, staring a whole host of Hollywood “names” (James Woods, John Heard, William Hurt, Paul Giamatti, Cynthia Nixon, Topher Grace, Ed Asner etc.). Sadly, it’s a fairly boring movie, albeit about a terrifically exciting piece of near-term history. It focuses on the collapse of Lehman Brothers, mostly through the eyes of Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson (played spot-on by William Hurt). Asner does a wonderful Warren Buffett (who almost, albeit reluctantly, came to Lehman’s rescue) and Giamatti is a wonderful Ben Bernake. (As an aside — Bernake is the most dead-pan person I’ve ever met. Giamatti’s version of Bernake is even more deadpan than reality.)

The movie gets one thing right and one thing wrong. First, the wrong, and then the right.

The movie keeps referring to Lehman’s “real estate”. No one will buy Lehman if they have to buy its real estate holdings, too. Lehman’s real estate “problem” is at first estimated at $40 Billion, then $70B, then “who knows”. The truth, of course, was “who knows”. Cynthia Nixon plays Paulson’s press secretary, who serve as an amiable foil to allow Paulson and his Chief-of-Staff Jim Wilkinson (Topher Grace) to explain the nature of the crisis to her (and thus to the viewer). Unfortunately, Lehman’s “real estate” isn’t “real estate” but “real estate mortgages”. More to the point, they have “tranches” of real estate mortgage pools, and to understand what a “tranche” is would be well beyond the capacity of a two-hour movie. Tranche, by the way, comes from the French word for “slice”. Imagine we pool $100 million or so in mortgages, then split up the ownership into three equal parts — an “A” tranche which will get paid in full, including interest, before anyone else gets paid; a “B” tranche which gets paid next, and a “Z” tranche which only gets paid after everyone else gets paid.

In theory, all three tranches should be good securities, since the underlying mortgages are pretty safe bets, and in practice the “A” and “B” tranches really were pretty good. However, the “Z” tranches will bear all the default risks. Banks (both mortgage and investment) made tons of money on these things, because the default risks could be “priced” as long as market continued to rise. Various investment banks then borrowed money to buy “Z” tranches, and coupled with credit-default swaps (essentially, a mutual insurance pact among investment banks), they were able to borrow huge amounts of money with very little capital.

The Paulson/Wilkinson explanation in the movie makes it sound like the whole problem came from mortgage defaults and foreclosures. In reality, mortgage defaults DO cycle up when a recession comes along, but these are usually predictable cycles. The REAL problem came from borrowing huge amounts of money — with almost no capital — to buy “Z” tranches that didn’t reasonably price the increased in defaults. A slight up-tick in defaults sent everyone to the emergency room, and when owners couldn’t sell or re-finance, the whole market went down the tubes. THAT was the “real estate” problem which plagued Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers, Salomon Brothers, Morgan Stanley (my old alma-mater) and all the others. Sadly, the movie perpetuates the myth that the real estate down-turn was an exogenous event, and fails to discuss the sins of the secondary mortgage market which took a simple, cyclical downturn and turned it into a long-term, world-wide crisis.

But, even with that, the movie got one thing so very right that made up for the mistakes. In one pivotal scene, Paulson and his team are presenting the TARP idea to the leaders of Congress. (Central Casting found some excellent look-alikes for Pelosi, Dodd, Shelby, Frank, and the rest.) Note that this comes very late in the movie, well after Paulson (an almost billionaire, who really didn’t sign on for this level of stress) and his team have tried ever possible solution to stem the crisis. The movie does a great job of playing Paulson up as the unsung hero who really saved the world’s economic life, by the way. Anyway, the leaders of Congress don’t “get it” until Giamatti’s Bernake gives the most important 2-minute economic lecture in history. He notes that while the Great Depression started with a stock market crash, it was the failure of the credit markets which made the depression last so long. The current crisis, if left un-solved, would spin the world into a much worse, much longer economic depression. Giamatti really nails the tone of the reality which was facing the nation’s top economic thinkers at the time.

Anyway, I don’t watch very many movies. I saw Adam Sandler and Jennifer Anniston in “Just Go With It” on an airplane last week, and thought it was a hoot. As movies come-and-go, “Too Big To Fail” doesn’t even rise to the entertainment level of “Just Go With It”, but as an educational piece, it’s a must-see, even with its critical flaws.

Housing Finance — Take 2

Again, from the Wall Street Journal, we find reasons for concern. The “Ahead of the Tape” column in today’s Journal, we find an excellent — but troubling — article by Kelly Evans titled “Economy Needs a Borrower of Last Resort.” It really follows my theme from yesterday, and I couldn’t agree more.

The first line of the article says it all: “A lack of funds isn’t hampering the U.S. Economy right now. It is a lack of demand for them.” The FED has been pumping billions into the money supply by buying bonds from banks. In a healthy economy, this should drive up the money supply by a multiple of the face amount bought. Why? An old equation from Econ 101 called the “Velocity of Money.” When I was teaching, I explained (or tried to, for the C students) that when the FED injects money into banks, the banks loan it out. The borrowers in turn buy stuff and the money goes back into the banks, minus a little. That happens several times over. Thus, a dollar of money “injection” by the FED should usually result in at least $2 of net M2 money creation.Imagine a dollar (or a hundred thousand dollars) injected into the system which is loaned to a family buying a new home. They pay the builder, who deposits the money in the bank (actually, paying off the construction loan) and then that money can be loaned back into the system. Some of it bleeds off into taxes, exports, and such, with each iteration of the deposit-and-loan cycle, but still, the money cycles thru the system. Since each subsequent deposit and loan doesn’t happen instantly, there is a little bit of a lag. Nonetheless, over a short period of time, the system should work. The math behind this is called the “Cambridge Velocity Equation” and it’s been known to economists for hundreds of years.

So, since November, the FED has purchased $684 Billion in bonds, which SHOULD have resulted in trillions of dollars in new money creation. Instead, M2 (the abbreviation for the money supply, defined as all of the cash, bank deposits, and money market funds in the system) has only increased by $326 Billion, suggesting that the velocity of money is about 0.5. Note that it SHOULD be 2 or 3 or more in a vibrant economy. This means that for every dollar injected into the system by the FED, half of it has dissipated.

As the article points out, this is why the recovery has remained so anemic. I would posit that a big problem is in the home loan business, which is far weaker than merely “anemic” — it’s on life support with the undertaker waiting in the lobby.

Kelly Evans posits that the market needs a lender of last resort, which is exactly what I was saying yesterday. Unless and until the system starts turning into the skid, by fixing the totally busted mortgage market, a double-dip recession seems inevitable.

Housing — and today’s WSJ

The front page of the Wall Street Journal today is plastered with the story of the continued problems with house prices, courtesy of info from the S&P-Case Shiller Index. I’ve commented on this several times before in this blog, but it bears further investigation.

Prior post-WWII real estate recessions (if we can call them that) have been quickly self-correcting. Stagnation in house prices lead to increased investment, as buyers look for deals and bankers need to make loans. As such, real estate recessions rarely have actual price declines, but instead are marked with volume slow-downs or price stagnation.

This recession is very different. Bankers are highly reluctant to make loans, in stark contrast to prior recession-exits. Regulatory problems, lack of bank capital, a doubling of REO portfolios, lack of cash from retail buyers, and a real fear (by both bankers and buyers) that collateral values will continue to decline puts the market in a continued downward spiral. To make matters worse, since many owner/sellers (particularly the most fragile ones — in the “zero down payment” starter homes) are themselves faced with economic travail and often the need to move to find work, the potential for further foreclosures down-the-road is very real, thus further driving down prices. Add to this the fact that a very big chuck of the U.S. economy is housing-related (contractors, developers, bankers, realtors, and many other intermediaries), it’s easy to see that a sustainable jobs market is hard to envision without “fixing” the housing problem.

We can re-examine the causes of this crisis over and over, but very few analysts are focused on the cure. Pilots are taught that when airplanes stall and go into a spin or a downward spiral, after “pulling the power” the pilot has to do something that’s rather counter-intuitive: point the nose downward and actually fly INTO the stall to get out of it. It’s like steering a car INTO the skid on an icy road. It’s very counter-intuitive, but it’s necessary. (The “black box” — it’s actually orange — recently recovered from the Air France 447 crash showed that the two very junior co-pilots who were at the controls when the plane went into a stall tried to pull BACK on the stick, when they should have pushed FORWARD. If they’d thought back to “Flying 101” they might be alive today.)

The “thing missing” from today’s market is the national policy in favor of affordable housing, which was manifested through Fannie-Mae and Freddie-Mac. Pulling the plug on the secondary market (which was at the core of the housing bubble) basically took our financial markets out of the housing business. Now that the price-bubble has bursts, our financial markets need to step back up to the plate and provide some liquidity. Admittedly, a “fixed” market will need to provide better risk-measures and possibly some hedging tools, but these are details that can be worked out once we get the plane flying again. I hate to say this — I’m generally a “free-market” kinda libertarian guy — but the government will need to step up to the plate as a guarantor of last resort…. and yes, I know the U.S. government is effectively broke. However, until it gets the housing market back on its feet, it’s going to stay broke. At some point, they need to steer the car into the skid.

Apartment Investing — Cap Rate Divergence

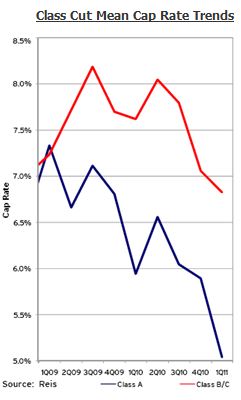

The fact that apartment “cap rates” are declining in the face of rising fundamentals is old news. (For the newbies — the “cap rate” is the ratio of net operating income, or NOI, to value or purchase price. If NOI is rising, then purchase prices must be rising even faster, indicating increased investor sentiment.) Indeed, as of April, nationwide, mean cap rates on apartments were back to early 2008 levels. (Again, for the newbies — cap rates on all property types rose during the recession, reflecting both declining fundamentals AND declining investor sentiment.)

The more interesting piece of news comes out of our friends at REIS, who just released a report today showing that Class “A” apartment cap rates have declined much faster than Class B/C, indicating that high-end, investment grade properties are much in favor today for their income by institutional investors.

Those same investors are wary of lower-grade apartment investments, although REIS suggests that this wariness should dissipate over time. This suggests some significant opportunities for developers, turn-around specialists, and other non-institutions during the coming months.

Mueller’s Market Cycle Monitor

Sorry it’s been so long — I’ve been traveling a good bit lately, and it’s hard to keep up!

One of my favorite real estate pieces hit my desk while I was gone — Dr. Glenn Mueller’ Market Cycle Monitor, published by Dividend Capital. He developed this model about 15 years ago, and it tracks occupancy and absorption of major commercial property types in about 50 geographic markets. As a property type (in a given market) sees increasing occupancy, market participants bring new property on-line. This creates an expansion. At the peak of the expansion curve, “hypersupply” begins, following which the new supply exceeds the market ability to absorb property. Vacancy rates increase, even as new property is still coming on line. This stimulates a recession. During the recession, no new property comes on-line, and occupancies hit a nadir. At that point, natural expansion of the economy stimulates a recovery, during which excess properties are absorbed and the cycle continues. The following, taken from Dr. Mueller’s excellent 1995 paper, captures the entire idea:

Currently, the market can be best described as “flat-lined”. Office occupancies were flat during the first quarter, and rents were actually down slightly (0.3%, on an annual basis). Industrial occupancies improved slightly, but rents actually fell signficantly (3.1% annualized). APartment occupancies improved slightly, and rental growth improved significantly (2.8% annually). Retail occupancy actually improved significantly, but rental growth trended downward (3.1% annually). Finally, hotel occupancies improved a bit (0.8%), and hotel income (measured as RevPAR, or Revenue per available room) increased 8.9% on an annualized basis.

For a complete copy of Dr. Mueller’s report, click here or write us at info@greenfieldadvisors.com.

Phily Fed — Econ Forecast

One of my favorite economic touchstones is the quarterly survey of professional economists by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank. Forty-four economists are surveyed, including such notables as Mark Zandi from Moodys, John Silvia from Wells Fargo, and Neal Soss from Credit Suisse. The focus is on “practicing” economists rather than “academics”, and as such gives a great snapshot of what decision makers at major corporations are thinking.

The Phily Fed then takes a synopsis — both a mean and a distribution — of their collective thinking in several key areas, such as Real GDP growth, unemployment, monthly payroll growth, and inflation. The interesting factors include both the current thinking, the CHANGE in current thinking (from the previous projections) and the probability distribution.

Current thinking about GDP growth is a bit less optimistic than it was before. As noted in the graph below (reproduced from the Phily Fed’s report), prior consensus thinking put GDP growth in the 3.0% to 3.9% range, while the current consensus mid-point is between 2.0% and 2.9%. Good news — hardly anyone projects negative GDP growth for this year. As we get into out-years (the graphics are on the Phily Fed’s report), which you can download by clicking here ), the consensus is a bit blurry, but in general most economists still see GDP growth postiive and between 2% and 4%. Unfortuantely, this isn’t the best of news — for the U.S. economy to really get back on track, much stronger GDP growth is needed (solidly high 3% range and even above 4%).

Unemployment projections for 2011 are somewhat rosier. In the prior survey, the mean projection was in the range of 9.0% to 9.4%, with a significant number of economists projecting from 9.5% to 9.9%. Currently, the mean is 8.5% to 8.9%, and a signficant number project in the 8.0% to 8.4% range — a very real shift in the outlook for the nation’s economy as we head into the second half of the year. On the downside — projections for out-years (2012, 2013, and 2014) show a very slow restoration of “normality”, with mean unemployment projections above 7% in all years.

One piece of good news — and this may be the FED patting itself on the back a bit — is that its inflation projections have been quite accurate over the years, and they continue to forecast exceptionally low CPI changes over the next ten years. While the median forecast is up slightly from last quarter (2.4% up from 2.3%), this continues to be great news for consumers and bond-holders. Notably, as you can see from the graphic, there is a fair degree of agreement among economists surveyed — the interquartile range is less than a percentage-point.