Archive for the ‘Inflation’ Category

PWC’s Emerging Trends in Real Estate for 2016

Ever since PWC acquired Peter Korpacz’s excellent quarterly commercial real estate survey, they have really leveraged that theme into a great regular read. Along with my subscription, their annual Emerging Trends just landed in my in-box, and it’s a really excellent read. (To access a copy, just click on the link above.) The report is a must-read for anyone in real estate, particularly in the investment or finance side. I’ll skip to two of the summaries — one they call “expected best bets” as well as the capital market summary, to give you a flavor of their report.

Expected Best Bets — PWC recommends, “Go to the secondary markets”. They note that gateway markets have pricing problems, while the “18-hour cities” are “…emerging as great relative value propositions.” They particularly cite Austin, Portland, Nashville, and Charlotte.

PWC also discusses “middle-income multifamily housing,” and notes the solid business opportunities providing creative answers for what they call the “excluded middle” households. PWC also encourages planners to re-think parking needs, in light of the changing demands of “live/work/play downtowns.”

On the securities side, PWC notes that many REITs are priced well below net asset value, providing an interesting arbitrage opportunity in 2016.

Capital Markets — PWC opens by noting, “In many ways, it appears that worldwide capital accumulation has rebounded fully from the global financial crisis. The recovery of capital around the globe has been extremely uneven. And the sorting-out process has favored the United States and the real estate industry, affecting prices, yields, and risk management for all participants in the market.”

Whew…. I’m usually loathe to quote so much from another’s work, but I simply could not have said that any better. PWC quotes one of their survey respondents, a Wall Street investment advisor, who says, “There is going to be a long wayve of continued capital allocation toward our business….”

Survey respondents largely were split on short-term inflation, with about 40% predicting modest increases and 60% looking for stability at current rates. However, when they look down the road 5 years, 80% of respondents look for modest increases in inflation. Coupled with that, over 60% of respondents think both short term interest rates and mortgage rates in specific will rise next year, and nearly 80% think such rises will occur over the next 5 years. Intriguingly, a small but significant minority — about 20%, believe rates will rise substantially over the next 5 years. Almost no one believes rates will fall, either in the short-term or the long-term.

To sum up the capital markets view, PWC says the general spirit of the industry is positive, albeit with an eye toward risk. Many are calling for a “long top” to this recovery, but many are also taking defensive postures by shortening investment horizons, paying more attention to the income component of total return rather than the capital appreciation component, and moving down the leverage scale.

As always, I would stress that I am citing a 3rd party source here, and nothing in this review should be construed as investment advise. That said, PWC’s Emerging Trends is an excellent read, and I highly recommend it.

whew…..

The gap in postings is a good indication of just how busy I’ve been the past several months. Whew….

Anyway, the latest semi-annual Livingston Survey just hit my desk from the Phily FED. Just to remind you, the Phily FED surveys a cross-section of top economic forecasters on four key issues — GDP growth, interest rates, unemployment, and inflation. Ironically, the survey came out before this week’s BEA announcement that GDP grew at an annual rate of 4.1% in the 3rd quarter (following a 2.5% growth in the 2nd quarter).

Nonetheless, the Livingston Survey gives a good snapshot of where professional forecasters think the economy will be over the next couple of years. Forecasters generally see GDP growth ending this year around 2.4%, increasing to an annualized rate of 2.5% early next year, and 2.8% in late 2014.

Interest rate forecasts were also surveyed before the recent FED pronouncements about tapering, although the general sense is that markets have been capturing the “taper” news for a while. Forecasters project t-bill rates to continue below 0.1% into 2014, rising to 0.15% by the end of next year, and 0.75% by the end of 2015. Ten-year bond yields should follow suit, with rates rising above 3% in mid-2014, up to 3.25% by the end of next year. Of course, time will tell on these projections.

Finally, unemployment is projected to dip below 7% after mid-2014, and finish the year around 6.7%. Inflation should hold below 2%, although it is projected to creep up somewhat from the current rates.

The Phily FED produces a series of economic surveys throughout the year. For more information, visit their research department.

Quarterly Econ Survey from Phily FED

One of my favorite regular “reads” is the Survey of Professional Forecasters” from the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank. The main survey comes out quarterly, with occasional special editions thrown in along the way. The brilliance of the survey is its simplicity — ask a large panel of economic forecasters where they think the economy is going in terms of a handful of key indicators — GDP, unemployment, inflation. Then calculate the median and the range of responses.

The medians are fairly predictable and “sticky” (that is, this quarter’s results look a lot like last quarter’s). However, the interesting stuff is buried in the way the distribution of results change. For example, both the last survey and the current survey find that the largest number of economists think unemployment will average between 7.0% and 7.4% next year (with a median of 7.1%), down somewhat from this year. That’s pretty predictable stuff. However, this year’s distribution is skewed to the low side (a very large number of economists think unemployment will dip this year and end up as low as 7% on average) but next year, the distribution is fairly even, with the bulk of economists forecasting anywhere from 6% to 8%. In short, 2014 is pretty cloudy right now, and that means that hedging your economic bets isn’t a bad idea.

GDP projections are somewhat less rosy. In the previous survey (2nd quarter, 2013), the largest number of economists projected 2013 GDP in the 2% to 3% range, with the median at 2%. Today, that has dropped a full half-percentage point, down to 1.5%. Previously, 2014 was projected at 2.8%, and that has now been downgraded to 2.6%, although as we’ve already established, 2014 is pretty much a guessing game.

Inflation continues to be pretty-much a flat line, with a lot of “1.8%” and “2.0%” on the chart. In short, hardly anyone sees inflation above 2.3% or so in the foreseeable future.

To download the full report, go to http://www.philadelphiafed.org/research-and-data/real-time-center/survey-of-professional-forecasters/2013/survq313.cfm

The right number of new homes?

Much has been said in recent days about the Census Bureau’s August 23rd announcement about new residential home sales in July. To summarize, 372,000 new homes were sold last month, which is 25.3% above the July, 2011. This is good news for a lot of reasons — construction workers get jobs, banks get new loans, etc., etc.

Naturally, it begs the question, “what’s the right number of homes?”. Here at Greenfield, we’ve posited that the U.S. housing price “bubble” was really a demand bubble, fueled by easy money, which led to an artificial inflation of the nation’s home ownership rate. (Housing bubbles in other countries were fueled by similar problems.) We’ve also suggested that the market won’t get healthy again until several things happen, including a stabilization of the homeownership rate at long-term equilibrium levels, a restoration of “normal” conventional lending (both for home mortgages as well as for development financing) and a restoration of the housing infrastructure (development lots in the pipeline, local regulatory department staffing, hiring & training skilled construction workers, etc.) . It is highly doubtful that we’ll see housing starts and new home sales “bounce back” to normal levels anytime soon, and our own projections suggest several years before we get back to “normal”.

But this begs the question: What’s normal? (A great t-shirt from the Broadway play, “Adams Family” simply said, “Define Normal”.) Anyway, as new home sales go, it’s helpful to glance at the experience over time. It may surprise you.

One might actually expect the graph to be less erratic, but there are good explanations for the “bobbing and weaving” you see from year to year. During recessions, new home sales decline, and then bounce-back afterwards. During periods of economic overheating, the FED tightens the money supply, thus causing home starts/sales to decline. (In practice, this is a major tool in the FED’s toolkit, simply because it has a great multiplier effect on the economy.) Of course, the bubble is quite apparent, and following it the inevitable decline.

With all that in mind, though, we can see that there is a decided upward trend in the chart — that makes sense, since a growing population, coupled with a fairly consistent homeownership rate, will generally demand more new homes each year than it did the year before.

The second graphic adds a simple linear trend line for simplicity sake, which is not far removed from the actual household formation trend line during that same period. Note that from the beginning of the chart until about 2001, we had a nice cycle going, and in fact around 2001, the blue line should have turned negative to account for the recessionary impacts. However, money got very loose during the early part of the last decade, and rather than housing starts serving its normal “pressure relief” role, it was driven into a counter-cyclical path. This created the oversupply we are now trying to work through (often referred to as the “shadow inventory”) and we won’t see a healthy market until this inventory is mopped up.

Good news, though — if you glance quickly at the second chart, it becomes clear — albeit from a very simple visual perspective — that we must be close to a spot where an up-turn in the chart would give us as much negative area red line as we had during the previous cycle above the red line. In short, we’re not at the end of the tunnel yet, but this simple way of looking at things suggests we may be able to SEE the end of the tunnel in the not-too-distant future.

REIT Fundraising on the Rise

According to SNL Financial, U.S. Equity REITs have raised $35.27 Billion through August 10th, over 10% more than was raised during the similar period last year. Continuing with the debt/equity theme we noted in a recent post, senior debt only constituted about 38% of this total ($13.53 B) with the remainder coming from common equity ($14.72 B) and preferred equity ($7.02 B).

Interestingly enough, Health Care REIT had the largest stock offering at $810.8 million, followed by Kilroy at $230.5 million and Taubman Centers at $281.5. All three of these are notable, as none of them are in the “hot” apartment sector. Indeed, of all of the sectors, health care raised the most at $7.7 Billion, followed by retail at $7.61 B.

The bigger question, of course, is what does this say about the real estate market? REITs buy cash flow, not capital growth, and respond to investor demand for something to take the place of flat-lined bonds. Given the risk of holding long-term bonds in an up-ticking interest rate market, compared to the yield margin and inflation hedge of REITs, this may be less a commentary on the quality of the property market and more a comment on the demand for REIT shares.

S&P Case Shiller Report

I WISH I could be excited about the most recent home price index report. I really wish I could.

The news is mediocre, at best — home prices in April rose by 1.3% on average from their record lows in March, and are still down 2.2% (for the 10-city composite) from April, 2011. Not surprisingly (after March’s terrible news), no cities posted new lows in April. Of the 20 cities tracked, 18 showed increases (NYC and Detroit being the exceptions).

So, why? If you read my blog yesterday, you know we have a terrifically supply-constrained market. This morning’s Wall Street Journal had an article about Chinese investors who are providing about $1.8 Billion in kick-start capital to Lennar to get a big 12,000+ home community underway in San Francisco — a project Lennar has been working on for 9 years. While I congratulate the Chinese and Lennar for this partnership, it does not at all bode well for U.S. investment liquiity that off-shore capital is needed to get a new project off the ground in one of America’s most dynamic cities.

Recall from ECON 101 that “price” is what happens at equilibrium when supply intersects with demand. (OK, technically “price” can emerge in disequilibrium, as well.) Right now, supply is hugely constrained, with a lot of REO-overhang and little new construction. If demand was healthy and growing, prices should be soaring. Instead, prices remain flat-lined, suggesting that demand is also stagnant. However, population continues to grow and household formation should be positive.

What’s taking up the slack? The apartment market continues to explode, with huge demand for rental units. What’s the end game for all of this? I can only think of two results:

1. The home ownership rate in America continues to languish, finding some new post-WW II low; or

2. Eventually, home ownership will go on the rise, and we’ll have an overbuilt situation in apartments.

Where would I bet? Sadly, given the state of the world’s economy, #1 looks more tenable in the long-term. That doesn’t mean we’re moving from being a nation of home owners to a nation of renters, but it does mean that the tradition of home ownership which has prevailed in the U.S. for decades may be becoming passe. Either way, in the intermediate term (the next several years), we’re probably looking at the status quo.

Retail — on the mend?

The Marcus and Millichap 2012 Annual Retail Report just hit my desk. It’s a great compendium — one of the best retail forecasts in the industry — and not only looks at the national overview but also breaks down the forecast by 44 major markets.

A few key points:

- What they call “sub-trend” employment growth will prevail until GDP growth surpasses 2.1% (we would add: “…sustainably passes….”) Increased business confidence will continue to transition temporary jobs to permanent ones.

- Most retail indicators performed surprisingly well in 2011, defying a mid-year plunge, a slide in consumer confidence, and a modest contraction in per-capita disposable income.

- The Eurozone financial crisis could undermine the U.S. recovery, but fixed investment will remain a pillar of growth, with capital flowing to equipment and non-residential real estate.

- All 44 markets tracked by M&M are forecasted to post job growth, vacancy declines, and effective rent growth in 2012.

- A rise in net absorption to 77 million square feet in 2012 will dwarf the projected 32 million SF in new supply, with overall vacancy rates tightening to 9.2%.

- However, some major retailers, most notably Sears and Macy’s, will continue to downsize or close stores that fail to meet operational hurdles.

- CMBS retail loans totalling $1.5 Billion will mature in 2012, but many may fail to refinance — about 81% have LTV’s exceeding acceptable levels.

- The limited number of really premier properties in the “right” markets will hit what M&M calls “high-high” price levels, moving some investors into secondary markets as risk tolerance expands and capital conditions become more fluid.

For your own copy of this research report, or to get on M&M’s mailing list, click here.

European Banking

I like Forbes magazine, and while I’ve only met Steve Forbes once, he’s seems to be a terrifically engaging fellow. That having been said, while he and I are probably not very far apart in our core political thinking, I DO disagree with him on many key points (gold standard being the top of the list). However, he wrote an excellent op-ed piece back in December about Angela Merkel and the actions/inactions which permeate European decision-making today. Recent events, particularly in Greece, suggest that Ms. Merkel may have read Mr. Forbes and followed suit. Nonetheless, I think some of Forbes conclusions may be ill-founded. (For a full copy of his article, click here.)

Forbes draws an analogy between the European actions of this past Fall with the draconian anti-inflation actions of the last days of the Weimar Republic during the great depression. Students of history may recall that those actions led to the fall of the German republic and the rise of Hitler. Forbes suggests that Merkel is frightened of the inflationary impacts of European central banks buying up Italian and Spanish bonds (thus pumping lots of Euros into the economy).

Forbes points out that banking is very different in Europe than in the U.S. He does not explicitly note — but seems to assume his readers would know — that Europe doesn’t have a system analogous to our Federal Reserve, but rather the major money-center banks serve that same purpose. (In practice, the European banks are joined at the hip with U.S. banks, and thus have an implicit liquidity guarantee from the U.S. Fed.) Forbes notes that liquidity is already strained in Europe, with U.S. money market funds having already withdrawn about $1 Trillion. In addition, European businesses look more to banks than bonds for raising long-term capital. In the U.S., industrial bank loans to nonfinancial corporations totals about $1.1 Trillion, while in Europe the corresponding number is about $6.4 Trillion. Contrast this with the bond market — in the U.S., corporate bonded debt is $4.8 Trillion, but only $1.2 Trillion in Europe. European banks are also the primary buyers of European government debt, while in the U.S. the banks are only one set of many sets of buyers.

I think where Forbes misses the point in his criticism is his failure to recognize that liquidity for this bond-buying spree would come not from a central source such as a Federal Reserve system but rather from German taxpayers. The Germans have bent over backwards already to bear the financial brunt of this crisis, mainly because they are apoplectic at the idea of the collapse of the Euro.

Forbes is also implicitly paying some homage to the Hamiltonian idea that a centralized, Federal Europe (which does not yet exist) could buy up bonds from member countries and issue a new “Euro Bond” which would take its place. The first U.S. Treasury Secretary came up with this idea for two reasons — first, the individual states were heavily in debt to pay for the Revolution, and second it would create a much stronger central government, which would issue a uniform currency and raise money through Federal taxes.

However, Europe of 2012 isn’t nearly as well organized as the U.S. of 1790 (amazing, but true). Plus, even if Angela and Nick (remember — Sarkozy gets a vote, too!) could wave Harry Potter’s wand and create a unified Federal Europe, the burden would still be borne disproportionately. Northern European countries (and even Northern Italy, which is more like Germany than pundits recognize) are quite healthy with the status quo. The peripheral countries (the “PIIGS” for short) are the principle problem right now. Back in the 1790’s, the debts of the various states were actually fairly well-distributed. (And yes, the irony of using Harry Potter as an example — a British wizard who still uses the Pound rather than the Euro — was on purpose.)

So, Forbes gets it half right. The model we now see in Greece may be the answer — a compromise on the bonds, with fiscal restraints borne by the countries that are in trouble. Will Europe ever see a Federal system with the same sort of fiscal and monetary controls we have here in the U.S.? Probably not for a long time. In the meantime, Angela has to play the cards she’s dealt, not the ones Forbes would like to imagine she has.

A truly dumb idea

First, there is virtually NO chance that this idea will come to pass, thank goodness.

SOME pundits propose shutting down the Federal Reserve. I’m serious. Presidential candidate Ron Paul considers it a central tenet of his philosophy. He would put us back on a gold standard, which would mean that the government could only issue paper dollars if they were backed by gold holdings (i.e. — Ft. Knox), and would stand ready to buy gold at a stated price. One assumes that gold coins would also circulate, although at today’s rates, the smallest gold coin available today (1/10 oz) would be worth about $150. Hardly the sort of thing you’d use in a vending machine.

From an economists perspective, it’s impossible to imagine a 21st century nation — particularly one with the most complex economy in the world — to exist without a central bank. In the first decade of the 20th century, the U.S. suffered a tremendous depression, much of which was driven by bank liquidity problems (and thus bank failures). To address this, the U.S. Government established not one central bank but in fact a network of regional central banks, all of which would coordinate their activities via a central Federal Reserve Board. Members of the Federal Reserve Board are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate for 14-year terms, a period of time selected to make sure that no ONE political party or political philosophy would dominate. The members of this board, along with a rotating subset of the Presidents of the regional banks, form what is called the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

The FED really only has two tools at its disposal. Taken together, these tools are called “monetary policy”. It can set the “Fed Funds Rate” which is the rate at which member banks can borrow money for short periods of time. Since member banks borrow (and pay back) constantly, this is an extraordinarily important base-line for interest rates. A rise in this rate would stimulate a rise in overall rates throughout the economy. Currently, this rate is about a half percent — nearly inconsequential. Clearly, the FED wants to keep rates low to stimulate the economy. A hint of inflation in the market would probably stimulate a rise in rates, to slow the economy down a bit and thus negatively impact inflation. The FED can also buy and sell government bonds, and in fact can force member banks to buy and sell bonds. Buying bonds from the banks puts money into the economy that these banks can lend. Recently, the FED has been buying long-term bonds and selling short-term, to “twist” the yield curve.

The Government also influences the economy through “fiscal” policy, exerted through the Treasury Department. Keynesians would hold that the government can stimulate the economy via deficit spending. In the current economic crisis, the Fiscal and Monetary roles heavily intersected, particularly in the TARP funding under President Bush, and continued under President Obama, which used the full faith and credit of the Treasury to prop up our failing banking system. The FED was an active participant in that process, and indeed (as shown in the movie), Fed Chair Bernake really sold this process to Congress. As expensive as it was, and despite the political ramifications, it is beyond belief that any thinking person would have allowed our banking system to collapse. A few banks dying was inevitable (e.g. — Lehman Brothers), but the entire system collapsing would have put the U.S. in an intractably difficult position, probably carrying the entire world’s economy with it.

As pointed out in a CNBC report by Mark Koba this morning (click here for a link), its noted that a gold standard would both put limits on growth as well as impose short-run volatility. The American economy would, at least for short periods, be held hostage to the whims of gold traders. Further, production of gold in the world is probably insufficient to sustain reasonable levels of growth.

In addition, removing a relatively independent FED from the scene would leave the Treasury Secretary in an intractably politicized position. The U.S. has had 75 Treasury Secretaries over the past 225 years, from Alexander Hamilton to Tim Geitner. (Also 6 “acting” secretaries who were never confirmed by the Senate.) Many — if not most — have been contentiously fought over. (The first Treasury Secretary, Hamilton, was shot in a duel. The second was run out of office after being accused of setting fire to the State Department building.) Given the current contentiousness that permeates Capitol Hill, the notion of subjecting the American economy to the vagaries of Congress every 3 years sounds like something out of a third-world country, much less the most important economy in the world.

Fortunately, this proposal hasn’t a ghost of a chance. Nonetheless, the inanity of it begs our attention.

Predicting recessions

The onset of a recession is much like the onset of a bad cold, or perhaps the flu. You THINK you know you have it, and then the next morning you wake up feeling like you’ve been hit by a truck.

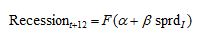

What if we had a tool that could actually PREDICT a recession a year or so in the future? Wouldn’t that be handy? In fact, two researchers at the New York Federal Reserve Bank actually developed something a few years ago (early 2006, to be precise) that seems to have some promise. They noted that the spread between 10-year Treasuries and 3-month Treasuries was a leading indicators of economic activity (which makes intuitive sense). Using historical data, they craft a formula which calculates the probability of a recession occurring in the coming 12 months:

…where “spread” is the difference, in percentage points, between the 10-year yield and the 3-month yield and F is the standard normal distribution (mean of 0, standard deviation of 1). Plotting their data over time, and comparing to the onset of a recession, they get Chart 2. While no model is 100% predictive, this one clearly indicates that a recession is highly probable whenever the spread-indicated probability gets much above 30%.

…where “spread” is the difference, in percentage points, between the 10-year yield and the 3-month yield and F is the standard normal distribution (mean of 0, standard deviation of 1). Plotting their data over time, and comparing to the onset of a recession, they get Chart 2. While no model is 100% predictive, this one clearly indicates that a recession is highly probable whenever the spread-indicated probability gets much above 30%.

Of course, the statistical math can get a bit hairy, but there is a handy rule-of-thumb. As you can see from Chart 1, whenever the spread turns negative, a recession is fairly likely in the coming months. Why? Because a negative spread suggests two things: first, that borrowers have little demand for long-term money, and second that investors are looking for a safe place to tuck money away that they don’t think they’ll need for a while, and aren’t afraid of inflation. In short, the yield spread constitutes a fairly accurate survey of investor expectations about the economy.

Unfortunately, Estrella and Trubin end their research with July, 2006, which at the time was giving off a 27% recession signal for July, 2007. A great test of their model would be to see if it would have predicted the onset of the December, 2007, through March, 2009, recession. We used the same H.15 data from the Federal Reserve Board, and came up with the following:

Unfortunately, Estrella and Trubin end their research with July, 2006, which at the time was giving off a 27% recession signal for July, 2007. A great test of their model would be to see if it would have predicted the onset of the December, 2007, through March, 2009, recession. We used the same H.15 data from the Federal Reserve Board, and came up with the following:

Ironically, our analysis shows that the probability of a recession crossed the 30% barrier on July 31, 2006 — a month after the cut-off of their study, and 16 months before the official “onset” of the recession.

By the way, if you’re worried, the current probability is at 1.8%. We’ll keep you posted.