Archive for the ‘Real Estate Investments’ Category

Housing Finance — Take 2

Again, from the Wall Street Journal, we find reasons for concern. The “Ahead of the Tape” column in today’s Journal, we find an excellent — but troubling — article by Kelly Evans titled “Economy Needs a Borrower of Last Resort.” It really follows my theme from yesterday, and I couldn’t agree more.

The first line of the article says it all: “A lack of funds isn’t hampering the U.S. Economy right now. It is a lack of demand for them.” The FED has been pumping billions into the money supply by buying bonds from banks. In a healthy economy, this should drive up the money supply by a multiple of the face amount bought. Why? An old equation from Econ 101 called the “Velocity of Money.” When I was teaching, I explained (or tried to, for the C students) that when the FED injects money into banks, the banks loan it out. The borrowers in turn buy stuff and the money goes back into the banks, minus a little. That happens several times over. Thus, a dollar of money “injection” by the FED should usually result in at least $2 of net M2 money creation.Imagine a dollar (or a hundred thousand dollars) injected into the system which is loaned to a family buying a new home. They pay the builder, who deposits the money in the bank (actually, paying off the construction loan) and then that money can be loaned back into the system. Some of it bleeds off into taxes, exports, and such, with each iteration of the deposit-and-loan cycle, but still, the money cycles thru the system. Since each subsequent deposit and loan doesn’t happen instantly, there is a little bit of a lag. Nonetheless, over a short period of time, the system should work. The math behind this is called the “Cambridge Velocity Equation” and it’s been known to economists for hundreds of years.

So, since November, the FED has purchased $684 Billion in bonds, which SHOULD have resulted in trillions of dollars in new money creation. Instead, M2 (the abbreviation for the money supply, defined as all of the cash, bank deposits, and money market funds in the system) has only increased by $326 Billion, suggesting that the velocity of money is about 0.5. Note that it SHOULD be 2 or 3 or more in a vibrant economy. This means that for every dollar injected into the system by the FED, half of it has dissipated.

As the article points out, this is why the recovery has remained so anemic. I would posit that a big problem is in the home loan business, which is far weaker than merely “anemic” — it’s on life support with the undertaker waiting in the lobby.

Kelly Evans posits that the market needs a lender of last resort, which is exactly what I was saying yesterday. Unless and until the system starts turning into the skid, by fixing the totally busted mortgage market, a double-dip recession seems inevitable.

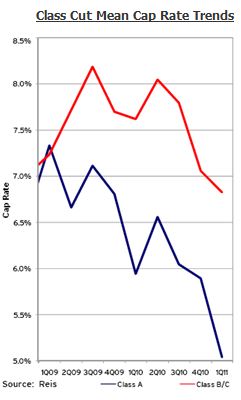

Apartment Investing — Cap Rate Divergence

The fact that apartment “cap rates” are declining in the face of rising fundamentals is old news. (For the newbies — the “cap rate” is the ratio of net operating income, or NOI, to value or purchase price. If NOI is rising, then purchase prices must be rising even faster, indicating increased investor sentiment.) Indeed, as of April, nationwide, mean cap rates on apartments were back to early 2008 levels. (Again, for the newbies — cap rates on all property types rose during the recession, reflecting both declining fundamentals AND declining investor sentiment.)

The more interesting piece of news comes out of our friends at REIS, who just released a report today showing that Class “A” apartment cap rates have declined much faster than Class B/C, indicating that high-end, investment grade properties are much in favor today for their income by institutional investors.

Those same investors are wary of lower-grade apartment investments, although REIS suggests that this wariness should dissipate over time. This suggests some significant opportunities for developers, turn-around specialists, and other non-institutions during the coming months.

Mueller’s Market Cycle Monitor

Sorry it’s been so long — I’ve been traveling a good bit lately, and it’s hard to keep up!

One of my favorite real estate pieces hit my desk while I was gone — Dr. Glenn Mueller’ Market Cycle Monitor, published by Dividend Capital. He developed this model about 15 years ago, and it tracks occupancy and absorption of major commercial property types in about 50 geographic markets. As a property type (in a given market) sees increasing occupancy, market participants bring new property on-line. This creates an expansion. At the peak of the expansion curve, “hypersupply” begins, following which the new supply exceeds the market ability to absorb property. Vacancy rates increase, even as new property is still coming on line. This stimulates a recession. During the recession, no new property comes on-line, and occupancies hit a nadir. At that point, natural expansion of the economy stimulates a recovery, during which excess properties are absorbed and the cycle continues. The following, taken from Dr. Mueller’s excellent 1995 paper, captures the entire idea:

Currently, the market can be best described as “flat-lined”. Office occupancies were flat during the first quarter, and rents were actually down slightly (0.3%, on an annual basis). Industrial occupancies improved slightly, but rents actually fell signficantly (3.1% annualized). APartment occupancies improved slightly, and rental growth improved significantly (2.8% annually). Retail occupancy actually improved significantly, but rental growth trended downward (3.1% annually). Finally, hotel occupancies improved a bit (0.8%), and hotel income (measured as RevPAR, or Revenue per available room) increased 8.9% on an annualized basis.

For a complete copy of Dr. Mueller’s report, click here or write us at info@greenfieldadvisors.com.

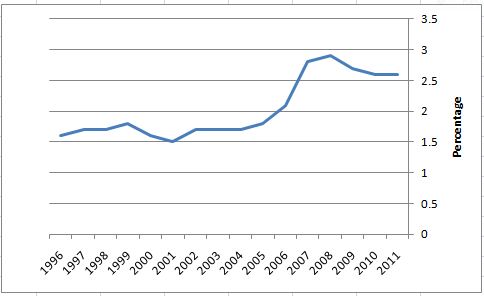

Home-ownership vacancy rates

Regular readers will recall that we’ve linked continuous decline in home ownership rates to price instability. In short, prices won’t start rising again until home ownership rates stabilize. (They’re down from about a recent peak of 69.5% to about 66%, and we believe they will continue to fall to about 64%). One MORE piece of important data just hit our desks, in the form of the Census Bureau’s 1st quarter home ownership survey.

The report is full of useful data. For one, the number of owner-occupied units in the U.S. actually fell from 1st quarter 2010 to 1st quarter 2011 (as we would expect), while rental occupancies continue to increase. Rental market supply (in essence, construction of new apartments) is keeping pace with demand, and rental vacancy is just below 10%, slightly lower than the 10% -11% range we’ve seen in the past few years, but not so low as to put inflationary pressure on rental rates. (Of course, this varies from one part of the country to another.)

Among “owner-occupied” homes, though, the vacancy rate continues to rise. See the chart below for a vivid explanation —

If this was a classroom exercise, I’d ask the students to identify the pre-recession equilibrium level, which appears to be about 1.6% to 1.8%. We can then identify the point-of-inflection signalling the impending disequilibrium in the housing market (when vacancy rates increased significantly — 2005). This inflection point, of course, signaled a great time to start shorting mortgage-backed securities, since it signaled the beginning of an increase in default rates. Of course, once can point at this and say “hindsight is 20-20”, but we know that the folks inside many of the banks, who were hawking mortgage-backed securities to their customers, were reading those very tea leaves back mid-decade, and shorting the very same securities they were promoting as safe investments.

Two quickies from the WSJ

Page C1 today has two important articles that caught our eyes. I’ll write about the first right now, and follow up with the other one later today. First, Kelly Evans contributes “Overlooked Inflation Cue: Follow the Money.” It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone that money supply growth in the western economies was rampant during the run-up to the current recession. In the U.S. and the U.K., M-2 growth peaked in late ’07 to early ’08 (you don’t have to be a monetarist to figure that out). The Eurozone kept pumping money at faster rates right up to mid ’09

Where money supply growth went from there, though, was a bit of a mixed bag. In the U.S., the annual growth in M-2 fell from a peak of about 12% right before the recession to a low of about 1.5% in early ’10, and has stayed below 3% since. (This basically supports my contention that the sturm-and-drang over QE-2 was all politics.) The U.K.’s growth rate peaked at about 9%, fell earlier than ours, and hit its bottom (about 2%) in mid ’09. Intriguingly, the U.K. money supply growth rate bounced back immediately, with the virtual money presses running full-speed to get the money supply growth rate back up to about 6% in early ’10, but then falling off to about 4% today.

In the Eurozone, the money supply growth tracked very closely with the U.S., bottoming with ours in mid ’10, but since then, the European bankers have started pumping money back into the system, with their M-2 growth rate headed continuously back upwards (at about 4% today).

There are two important implications for all of this (plus my afore-mentioned observation about QE-2). First, the three big western currencies are on decidedly different tacks. The idea of opposing viewpoints among the big western central bankers is not well explored in today’s decidedly multi-polar world economy. (Back when western banking was a closed system, everyone else in the world could only sit back and watch. Now that the Chinese — and even the Japanese with all their other troubles — are more than sidelines spectators, one can only wonder how disagreements among the western bankers will play out.)

Second, though, the really significant point is that despite all of the different paths of M-2 since 2009, all of the growth rates are decidedly down from the earlier peaks. From a real estate perspective, this has major implications. As investors diversify away from stocks, real estate and bonds have a certain equivalency. In a no- or low-inflation scenario, bonds are viewed as the more secure investment. In a higher-inflation world, real estate is viewed as a bond with a built-in inflation hedge. Hence, lower inflation portends well for bonds but poorly for real estate.

One might argue that healthy bonds means low interest rates for real estate, but this ignores the fact that interest rates are already at historic lows. Hence, what real estate needs today is a nice raison d’être, which a tiny bit of inflation would give it. I’m NOT pro-hyper-inflation, mind you, and inflation flat-lines are overall healthy for the economy. However, if real estate investors are hoping for an inflation kick, it doesn’t look like they’re going to get it.

A last minute edit — Later in the day, I noticed that yesterday’s USA Today had a “snapshot” (a little graphic in the lower left corner of the front page) titled “Which Investment Will Perform the Best”, taken from a survey recently conducted by Edward Jones. Topping the list was Technology (33%), follwed by Gold (31%), Blue-chip stocks (10%), Real Estate (9%) and International stocks (9%). Given that gold and real estate are both thought to be inflation hedges, it appears that the market still worries in that direction.

sushi or dead fish?

I’m at the semi-annual meetings of the Real Estate Counseling Group of America (RECGA), a small (capped at 30), invitation-only group of real estate experts founded by the esteemed Dr. Bill Kinnard back in the 1970’s. Over the years, RECGA members have included editors of major journals, presidents of various real estate academic and professional organizations, and advisors to major investment groups. We’ve nearly lost track of how many text books have been written by the members — well over several dozen, plus many hundreds of journal articles, book chapters, and scholarly papers.

A few somewhat random observations:

Investment activity is up, but the major impediments are lack of capital and excess inventory

Apartment “cap” rates are falling again, with lots of activity

The credit markets are still a mess, with no consensus on when they will be “fixed”

Wonderful presentations (patting myself on the back for one of them), with great interaction on complex issues in real estate analysis and valuation.

Why the title to this post? Simple — one real estate investor was quoted as saying, “The market today is like a platter of seafood. I have to figure out which are sushi and which are just dead fish.”

Gulf Oil Spill — Lessons Learned conference

I’ve just been confirmed as a speaker at the big one-year “Lessons Learned” conference on the Gulf Oil Spill, sponsored by Tulane University Law Center, American Lawyer magazine, and the Brickel and Brewer Law firm. The conference will be held at the Weston Canal Street in New Orleans on April 28th. I’ll be one of the “wrap up” speakers that afternoon, focusing on the impact of the oil spill on the value of bank collateral portfolios.

For more info on the conference, click here. Hope to see you there!

Appraisal and Financial Reporting

Real estate appraisers are, by and large, behind the curve as far as International Financial Reporting Standards are concerned. IFRS is already the norm in most of the world, and will integrate in the U.S. with our accounting rules in the very near future. The Appraisal Foundation recognizes that many (most?) appraisers lack the knowledge and training to compete in the this new realm, and is taking proactive steps to address the problem.

The “ying and the yang” of this — implementation of the IFRS, particularly following the real estate meltdown, will focus considerable attention on asset values rather than asset costs. This has become known as the “mark to market” phenomenon. In an era when everyone basically THOUGHT that asset values gallopped upward non-stop, reporting historical costs-less-depreciation was the norm, and a conservative one at that. However, in an era when real asset values have actually declined, the conservative approach is to mark these values to market. This necessitates regular appraisals. All well and good for appraisers, right?

Not so fast, bucko. There’s nothing in the IFRS that requires an appraiser, per se, and in fact appraisers are so out-of-touch with financial reporting standards that CPAs (who are ultimately responsible for the reporting) may be loathe to use appraisers for these assignments. At best, CPAs are described as “skeptical” on the contribributions to be made by appraisers.

One change will be the migration from “market value” (as is commonly preached to and by appraisers) to “fair value” which is enculcated in Statement of Financial Accounting Standards NO. 157. IFRS will converge Fair Value guidance with US Generally Accepted Accounting Principals with the pending issuance of IFRS 13.

Other changes include new thinging about “market participants”, “highest and best use”, and a concept totally foreign to appraisers, “levels of valuation input.” This latter creates a hierarchy: Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3.

Yesterday, the Appraisal Foundation sponsored a webinar featuring some great thinkers on this subject. Rather than get “down in the weeds”, they were good enough to keep the topic at 20,000 feet and thus cover a wide array of implications in a very short time. Clearly, there’s a lot of education and re-education needed if appraisers are going to have a role to play in this. In the meantime, appraisers can begin familiarizing themselves with the salient information at the IFRS web site, www.ifrs.org.

Conerly Consulting

Dr. Bill Conerly of Portland, Oregon, produces a wonderful little economic report called the Businenomics Newsletter. You can check it out here. While it is heavily Pacific Northwest focused, he has some great insights into the “big picture” of the U.S. economy as a whole. I highly recommend his research, and (as long as I’m in the promotion game), he’s a great public speaker.

He discusses two key elements of the “end of the recession” right up front — the current consensus forecasts of strong GDP growth for the next two years and the current “bounce-back” in consumer spending (which fell off significantly from mid-08 to mid-09). Unfortunately, capital goods orders are only sluggishly recovering, and state-and-local budget gaps continue to be a drag on the economy.

As for construction, the decline is over, but the bounce-back is sluggish. Residential construction fell from an annual rate of about $550 Billion in the 2007 range to about $250B in 2009, and continues to flat-line there. Private non-residential peaked at about $400B in 2008/09, and has since declined to about $250B (where it’s been hovering for since early 2010). Public non-residential has been on a bit of an up-swing all through the recession, but is still barely above 2007 levels (about $300B). In short, these three sectors taken together have more-or-less flat-lined for the past year and a half or so, and appear to be staying there for the time being.

Anyone who reads the paper or watches the news on TV knows we’re in the midst of a raw materials crisis, with aggregate materials prices (the “crude materials index) up about 25% from its recent mid-2009 low. However, the price index is still well-below early 2008. Conerly suggests that the rise is “hard on some, but will not trigger general inflation.”

The money supply (M-2) continues to grow, and QE2 has apparently not had an inflationary impact, at least from reading the charts. Indeed, prior to QE2, the money supply chart looked like it was ready to flat-line. In total, as Conerly notes, the stock market appears to be happy that the economy is growing again.

Mueller’s Market Cycle Monitor

Dr. Glenn Mueller’s Market Cycle Monitor just hit my desk from the folks at Dividend Capital. To access it, or some of their other great stuff, just click here.

I’ve written about Dr. Mueller’s work before — while his model isn’t able to forecast really major moves (like the “fall off the wagon” move of 2008/2009), his Market Cycle synopsis does a great job of assessing how various property types and submarkets are moving through the normal stabilized cycle of business. In short (and I’m sure he’d do a better job of explaining this than I could), at any given point in time, a market or submarket is in one of four investment states: Recovery, Expansion, Hypersupply, and Recession. The way market participants react to one situation drives the market forward to the next situation. For example, in the recovery phase, no new properties are coming on-line. Natural expansion of the market drives up occupancy, and with it rents. The subsequent shortage of space leads to expansion. Too much expansion leads to hyper-supply, in which too much property is competing for too-few tenants. This leads to recession. (In a very macro sense, that’s more-or-less what happened in 08/09, with the added problem that too many banks were trying to loan too much money and thus not properly pricing risk.)

The nuances of his model and report are too numerous to synopsize here. In short, he finds that on a national basis, every property type (e.g. — apartments, industrial, suburban offices) are in various stages of recovery, with the health facilities and senior housing being the closest to breaking out to expansion. Intriguingly, both limited-service and full-service hotels are following in close order.

He also tracks most of the top geographic markets in the country, and all of these are either deep in recession or in the earliest stages of recovery. No markets are close to break-out into expansion. The worst two markets (and “worst” is just relative here) are Honolulu and Sacramento, while the best (again, relative) are Austin, Charlotte, Dallas-Fort Worth, Nashville, Richmond, Riverside, Salt Lake, and San Jose. My home city of Seattle is ranked — along with a dozen others — deep in the heart of recession.