Archive for the ‘Finance’ Category

Mueller’s Market Cycle Monitor

Dr. Glenn Mueller’s Market Cycle Monitor just hit my desk from the folks at Dividend Capital. To access it, or some of their other great stuff, just click here.

I’ve written about Dr. Mueller’s work before — while his model isn’t able to forecast really major moves (like the “fall off the wagon” move of 2008/2009), his Market Cycle synopsis does a great job of assessing how various property types and submarkets are moving through the normal stabilized cycle of business. In short (and I’m sure he’d do a better job of explaining this than I could), at any given point in time, a market or submarket is in one of four investment states: Recovery, Expansion, Hypersupply, and Recession. The way market participants react to one situation drives the market forward to the next situation. For example, in the recovery phase, no new properties are coming on-line. Natural expansion of the market drives up occupancy, and with it rents. The subsequent shortage of space leads to expansion. Too much expansion leads to hyper-supply, in which too much property is competing for too-few tenants. This leads to recession. (In a very macro sense, that’s more-or-less what happened in 08/09, with the added problem that too many banks were trying to loan too much money and thus not properly pricing risk.)

The nuances of his model and report are too numerous to synopsize here. In short, he finds that on a national basis, every property type (e.g. — apartments, industrial, suburban offices) are in various stages of recovery, with the health facilities and senior housing being the closest to breaking out to expansion. Intriguingly, both limited-service and full-service hotels are following in close order.

He also tracks most of the top geographic markets in the country, and all of these are either deep in recession or in the earliest stages of recovery. No markets are close to break-out into expansion. The worst two markets (and “worst” is just relative here) are Honolulu and Sacramento, while the best (again, relative) are Austin, Charlotte, Dallas-Fort Worth, Nashville, Richmond, Riverside, Salt Lake, and San Jose. My home city of Seattle is ranked — along with a dozen others — deep in the heart of recession.

Two in one day?

Yeah…. Friday seems to be busy.

Two of my favorite newsletters hit my desk today — the Conerly Businomics Newsletter from Dr. Bill Conerly and the Philadelphia FED’s Survey of Professional Forecasters. You can reach the first one via the link on the right of this page (scroll down and look for Conerly). I’ll take a couple of minutes on the second one, though.

For quite a few years, the Phily FED has surveyed a host of leading economic forecasters (this quarter, it’s 43), and reported their median expectations on inflation, GDP growth, etc., as well as the dispersion around the median. The median gives a fairly good idea of the central tendency of economic thinking, and the dispersion measures let us know how “solid” that central tendency is. In general, this group tends to move together, which means that the dispersion measures usually aren’t very great, and when they’re wrong, they’re all wrong together. (Intriguingly, that means that economic markets are efficient but for unpredictable economic shocks. That in and of itself could lead to a wonderful discussion of Arbitrage Pricing Theory, but I don’t have time or patience for that…)

Even more interesting — and this may be the best stuff in the report — is the change in sentiment from one quarter to another. In short, how is new information being captured in economic forecasts? The magnitude and direction of change is often a more important element in the market than the absolute value of things. For example, prices are what they are, but the CHANGE in prices over time, and the magnitude of that change, is called inflation. Get it?

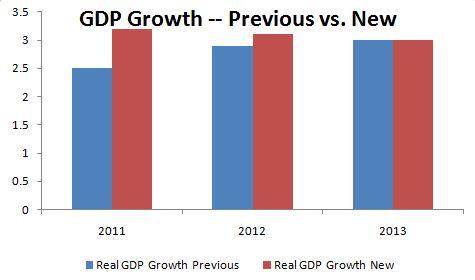

The following chart shows the consensus opinions on GDP growth for the coming 3 years. As you can see, there is a generally higher consensus for this year and next, and in fact (as not reflected on this chart) the biggest “jump” is in near-term growth rates, which are expected to be particularly robust during the first half of 2011.

Coupled with that, we see marginal improvement in the unemployment picture, although (and consistent with our own thinking) unemployment will continue to be a drag on the economy for quite a few years to come.

For a complete copy of the survey results, visit the Philadelphia FED by clicking here.

The death of the fixed rate mortgage

It might also be called the “death of the easy mortgage”, and will almost certainly be the death of the small-town lender….

The Obama Administration today outlined the broad-stroke strategy for dealing with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They suggest three solutions, all of which basically call for a multi-year wind-down of the two troubled institutions, which have cost taxpayers about $150 Billion in recent years to bail out.

How we got this way has been covered in thousands of articles, blog posts, and even text books. FNMA and FHLMC were set up to provide liquidity to small mortgage lenders (primarily, small-town S&L’s, of which there aren’t many now-a-days). A small-town S&L had a fairly finite pool of deposits, and once they made a few home loans (which were very long in duration), they simply couldn’t loan anymore until those mortgages were paid-off. Worse still, in times of rapidly changing interest rates, low-rate, fixed-rate mortgages didn’t get paid off, but depositors ran for higher-rate money funds. S&L’s were caught in a liquidity trap, and crisis after crisis ensued.

Today, of course, the mortgage lending business is filled with several thosand-pound gorillas with names like Wells Fargo, BofA, and JPMorgan/Chase. These institutions have the muscle to package mortgage pools and sell them off to investors. Why, then, do we have/need FNMA and FHLMC?

Congress is firmly on the hook for this one. Over the past decade and a half, the F’s were encouraged by Congress to morph into investors of last resort for mortgages that the securities market didn’t want. (It was actually a lot more complicated than that, but you get the general picture, right?) Why didn’t the private sector want these mortgages? Because they knew eventually many of them would go bad — and they did. Congress essentially got what it wanted, a subsidy of home ownership which, unfortunately, wasn’t sustainable.

This deal isn’t done yet, of course. Wait for the long-knives to come out from the Realtors and Home Builder’s lobbies. The current proposal would privatize all housing lending with the exception of FHA/VA lending. To put this in a bit of perspective, today, FHA loans constitute over 50% of housing lending. Back in the “hey-day” of the liquidity run-up, FHA loans were down around 4%. Without the F’s, we’re looking at a privatized mortgage market not far different from what we see out there right now, and that’s fairly unsustainable for the homebuilding industry.

Housing equilibrium — part 3

The Economist is simply the most informative magazine in the world today. If I came out of a coma, I’d want it as the first thing I read. One issue, and I’d feel fairly well caught up. The on-line version is an extraordinary supplement to the print edition, and may very well be a one-stop shop for economic research.

With all the obvious sucking-up out of the way (and no, I don’t get a free subscription — I pay for mine just like everyone else), the current issue has a stellar article titled “Suspended Animation” about America’s Housing Market. In prior missives on this blog, I’ve drawn linkages between the home ownership rate (currently at about 66%) and the housing bubble (best visualized with the Case-Shiller Index). The article makes that same comparison, without drawing the conclusions I do (see below).

When visualized this way, the linkage becomes fairly clear and obvious. Nonetheless, the real question is “where is the bottom”. There is significant anecdotal evidence to suggest we may be closing in on it right now, but then again, there’s some evidence to the contrary. On the plus side, a LOT of speculative cash is entering the marketplace right now, and about a quarter of all home sales in America are cash-only (see the front page of the February 8, 2011, Wall Street Journal). More interestingly, in the hardest-hit places, such as Miami, this percentage is approaching 50%. From a pure chartist perspective, we note that the C-S index has been “hovering” around 2003 prices for several quarters now. Back in my Wall Street days (LONG before the movie of the same name), the technical analysts would talk about “bottoms” and “breakouts” and such. Of course, residential real estate is not a security, per se (although mortgages are), and the comparisons fall apart at the granular level.

On the down side, the Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac controversies continue to simmer. The Obama Administration and the Republicans in Congress are finding common ground hard to find. The “Tea Party” Republicans want the government out of the home lending business entirely, which means privatizing the F’s. This idea is getting no traction at all among the Realtors and the Homebuilders, two typically “Republican” groups who generally sound like Democrats on this issue. One might blame this on grid-lock, but these are fundamental issues regarding the government’s role in the housing market which date back to the Roosevelt administration. Congress — both Republicans and Democrats — emphatically wanted to goose the home-ownership rate over the last twenty years, and empowered the F’s to do that. After that, the Law of Unintended Consequences got us where we are today. Now, in the words of Keenan Thompson on Saturday Night Live, everyone wants congress to “just fix it!” but with no solution in sight. Until this gets “fixed”, house prices will, at best, probably bounce along where they are today.

Movie reviews now? Say it ain’t so!

About half the movies I see are on a 5 X 8 screen on the back of the airplane seat in front of me. Fortunately, I fly Delta, generally coast-to-coast, and they usually have a pretty good selection, particularly up front where the drinks are comp’d. (Note — I said “comp’d”, not “free”. There’s a critical economic difference, but I digress….)

Anyway, last night, I flew in from Memphis and watched “Wall Street — Money Never Sleeps” with Michael Douglas and a first class supporting cast. The important thing to note is that it was “done” (written, directed, etc.) by Oliver Stone. This was very much an Oliver Stone movie, and that means it had a very obvious message and a very obvious point of view. Like many (most?) Stone movies, this one was set against the backdrop of very real events (the market melt-down, the Lehman Brothers collapse, the housing finance crisis) but then superimposed a very fine but fictional story which fit the events in question. Stone had the advantage that the events of the past few years were absolutely perfect for a Gordon Gekko reprise, played with his normal scenery-chewing skills by Michael D. Even Charlie Sheen made a one-minute cameo, reprising his character from the original W.S. just to bring closure to that story arc (and provide a very obvious product placement for a firm that, by weird coincidence, called me trying to solicit my business today.)

Yes, I liked the movie, from the perspective of a piece of fiction. However, even though the events of the past three years fit perfectly into Stone’s world-view, I none-the-less have to pick a bone or two with him over the tone of the movie. The characters, with the possible exception of the highly flawed “young male engenue” (played surprisingly well by Shia LaBeouf) are all portrayed as greedy, soul-less SOB’s for whom making obscene amounts of money is just a way of keeping score of how many of their friends/competitors they’re able to screw. Every single character in a suit is made out to be driven by sheer greed and lust for money, without a single redeeming quality. Even the one supposedly “good” character — Winnie Gekko, Gordon’s estranged daughter, played without a single smile in the whole movie by Carey Mulligan — is so deeply flawed by her relationships with her Dad and her dead brother that she lets Gordon rot in prison rather than visit him. (Ironically, the plot begins with her in love with LeBeouf, who at the start of the movie is essentially a 30 year old version of her father. As he goes through his painful and inevitable redemption process, she rejects him at the very points in his life when he probably needs her the most… but I’m digressing again, aren’t I?)

I’ve had the pleasure of working in finance for a long time — over 3 decades — and a fair chunk of that was spent on Wall Street (Dean Witter). The vast majority of the folks I knew, from the bottom to the top, were honest, family oriented, hard working, pillars of their communities. They really saw themselves performing the twin public services of financial intermediation, which is providing quality investments on one hand, and providing capital and liquidity for business on the other. Unfortunately, some terribly bad mistakes were made during the run-up to this crisis, mainly in terms of the financial products which did not properly account for or manage the risk of an increase in the foreclosure rate. As it turns out, a very small increase in household foreclosures, precipitated by a lot of things (not the least of which were borrowers who shouldn’t have borrowed) set off a cascade that got us where we are today.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been in PLENTY of forums, panels, and meetings with financial “types” from every facet of the money industry, who are focused on one and ONLY one thing — trying to get the system fixed. Do these folks get paid well? Yes, they do. A small handful of them are paid obscene amounts of money, in the same way that a small handful of baseball players get paid obnoxiously well, too. At the top of any game, there are a handful of extraordinarily talented folks who work very hard and get paid obscenely. But, 99% or more of the folks in the finance industry are paid “well” (not “Gulfstream G-IV” money, but “I get to ride in first class most of the time” money). They work hard. They want to see the system work, and they know just how important it is to the whole world for this system to get fixed.

So there it is. Watch “Wall Street” as a very well done piece of fiction, but please recognize that Stone’s characterization of the Finance community is highly skewed and w-a-a-a-a-a-y off base.