Posts Tagged ‘housing market’

Some Thoughts on Housing Crisis

Last month, I had the very real pleasure of delivering a major, hour-long address at a conference in Charleston, South Carolina, on the nation’s housing crisis. In it, I discussed the overarching problem and some potential solutions, as well as some problematic ideas which are being bandied about. I’ll synopsize here today.

Right now, we have about 131.5 million households in America, a number which has been growing steadily almost without a break since WW-2. Right now, we ad about one and a quarter million households to that total each year. About two-thirds of us live in owner-occupied dwellings, a number which has remained constant for most of my lifetime.

Just focusing for a moment on the owner-occupied sector, median house prices have gone up about 317% since 1991. However, median household income has increased only about 167%. Over the past three decades, owner-occupied housing has only appeared to be affordable most of the time because (1) we had a sub-prime bubble with artificially easy money in the 1990’s, and then (2) we had very easy money – in fact, a liquidity flood — following the meltdown, and then (3) we have had extremely low interest rates until just a couple of years ago. Owner-occupied demand spiked during the recession, and as everyone knows, cheap money disappeared. Those of us with long memories recognized that today’s supposedly high interest rates were actually the norm a few decades ago. If the FED target of 2% inflation is achieved, it is still very hard to imagine mortgage interest rates coming down much below 5%.

In a reasonably efficient economy, home prices rising would stimulate homebuilders to flood the market with new product. However, a new home is the nexus of several different inputs – materials, skilled labor, land, and ‘soft costs’ (insurance, permits, mitigation fees, taxes, fees, etc.). Unfortunately, these inputs have all been problematic. Material, land, and soft costs have all risen rapidly, and skilled labor is in short supply. In many ways, builders are in worse shape than their customers.

In 2020, the Goldman Sachs housing affordability index stood at 135%, which meant that a median household had 135% of the income necessary to ‘afford’ payments on a typical 30-year conventional mortgage (with 20% down) on a median priced dwelling. Today that index stands at 70%. It is widely agreed that getting that index back up above 100% will be a herculean task.

By the way, what do we mean by ‘affordable’? In general, the total housing burden shouldn’t exceed 30% of a household’s take-home income. What do we mean by ‘housing burden’? For a homeowner, that includes payments on the mortgage (principal and interest), plus homeowner’s insurance and property taxes. Not only have mortgage interest rates soared in recent years, but also, we’ve seen insurance and property tax rates climb at above-inflation rates. While mortgage interest rates may come down in the near future, higher insurance and tax rates may be with us permanently. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that those will actually continue to significantly increase, particularly in hard-hit areas like California and Florida.

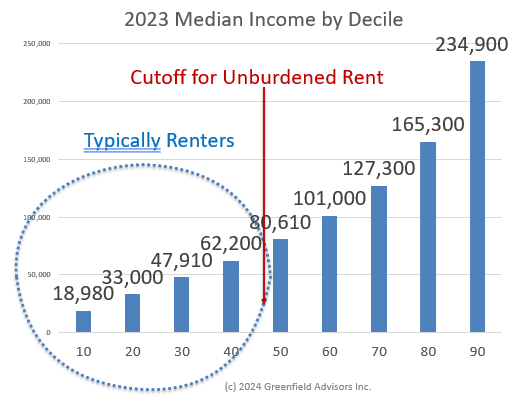

Amazingly, the rental community – about two-thirds of American households – have actually been hit worse. Note that as a general rule of thumb, renters come from the lower deciles of the income strata. Right now, the median household income in America sits at about $80,000 per year. However, the median income for the 40th percentile of Americans is only about $62,600. In other words – and this is a very rough approximation – about 40% of American households make less than about $62,200 per year. And remember, these households are more likely to be renters.

Right now, the median apartment rent in America is $1,595 per month. (The median rent on a single family detached dwelling is $2,000). Add to that about $300 per month for utilities and such, multiply by 12, divide by 30% (the threshold for ‘unburdened’ rent) and you get a household income of $75,800 per year to be considered ‘unburdened’ renting a median apartment in America. And remember, that’s a median, so fully half of the apartments in America are unaffordable for households making $75,800 per year.

Nobody in the bottom 40% of households makes that much money.

Indeed, an estimated 20 million households in America spend over 50% of their income on housing.

So how do we address these problems? We have two major sources of aid for low-income housing. First, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program provides indirect Federal support in the form of tax credits for developers of affordable housing. This program was created out of the 1986 Tax Reform Act, and until 2016 was responsible for building about 115,000 affordable units per year. However, since 2016, for a variety of reasons, the program has only helped finance about 75,000 units per year. As a result of this, in most of the country, we have fewer than 45 affordable and available units for every 100 low-income families, and in the hardest hit states, such as California, Florida, Virginia, and my home state of Washington, the number is under 30 units.

The other major source is the Section 8 voucher system. Funded by the Federal Government through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), but administered by local governments, this program provides full or partial rental vouchers for needy families earning less than 50% of local median income. However, the wait times for a voucher are awful (averaging 28 months nationwide) and only about one in four eligible households ever receive anything.

David Holt, the Republican Mayor of Oklahoma City, speaking on TV talk shows this weekend in his role with the national mayor’s association, noted widespread agreement among the country’s mayors that housing availability and affordability was their number one concern right now. So, what can we do to fix the problem.

Three ‘fixes’ come to mind immediately. First, a bipartisan group of both Senators and Congressional representatives have co-sponsored the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act (Senate bill 1557 and House Resolution 3238). This bill would fix some of the long-standing problems in the program and increase credits overall by 50%. However, the bill is currently stagnating in committee, and even though it has some powerful sponsors, it is simply not at the top of anyone’s agenda right now.

Second, some expansion of the Section 8 program is long overdue. However, the incoming administration is all in favor of massive belt-tightening. In the case of Section 8, this is woefully shortsighted, as the economic problems caused by unaffordable housing far outweigh the cost of this program. However, the attitudes on Capitol Hill are decidedly negative.

Finally, I would propose some significant overhaul in the HUD loan program (known back in my boyhood as ‘FHA Loans’). These loans provide Federal insurance – at no cost to the taxpayers – for homebuyers who meet stringent credit requirements. The loans carry extremely low down-payments – very close to zero. In the early 1980’s, when mortgage interest rates were soaring, many states were allowed to use tax exempt bonds to fund state housing finance programs which routed funds into HUD loans. This was a win-win for all concerned, and the economic stimulus of expanded housing construction far outweighed any lost revenue to the Federal coffers. However, the spread between tax-exempt and taxable bonds was somewhat greater back then, and so there was some meaningful leverage to be applied in lowering the mortgage interest rates, particularly for first-time buyers. That said, some kind of program like this, most likely using HUD leadership, would go a long way to breaking the logjam.

There are, unfortunately, some dumb ideas out there. First, a recent RAND study indicates that local governments, despite meaning well, have actually gotten in the way of affordable housing construction. The local restrictions are myriad, but as a result, the cost of building a new, affordable apartment in California, as an example, has risen to about $1 million per unit. This is utterly unsustainable.

Second, the incoming administration has posed the idea of building new homes on Federal land. Time and space will not permit me to list and discuss all of the reasons why this is a bad idea. As examples, however, it constitutes an intolerable wealth-transfer from existing homeowners to new homeowners, it runs afoul of the Federal mandate that any transfer of Federally owned land be at market value, and let’s face it, there is little available Federal land in any of the places where people actually want to live.

Finally, the incoming Administration has made it a priority to re-privatize Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These private sector groups, with the implicit guarantee of the full faith and credit of the US Treasury, are the primary secondary market makers for mortgage loans. During the housing meltdown, they were in effect ‘taken over’ by the U.S. Treasury, under the auspices of the Federal Housing Finance Authority, and now all of their considerable profits flow into the U.S. coffers. Both political parties have agreed that reprivatization is a goal, albeit for different reasons. However, the devil is in the details here, and a slap-dash reprivatization of organizations with combined balance sheets exceeding $4 TRILLION, would, in some estimation, add considerable burden to the current mortgage interest rates.

In the end, though, the real crisis is less about housing and more about affordability. In the owner-occupied sector, for example, house prices have been going up, on average about 2% above inflation year-after-year since WW-2. That’s really not a bad thing. It means that home ownership is a really good investment and a nearly perfect hedge against inflation. Even during the housing crisis following 2006-ish, while house prices dipped, they soon reverted to the mean, and today house prices are about where they would have been had the housing crisis never occurred. Over the same post-world war period, household incomes generally also trended upward, more or less, until the 1970’s. However, since then household income has simply failed to keep up with the cost of housing. In short, this current crisis has less to do with the cost of housing and more to do with the stagnating fortunes of middle-class Americans.

As always, if you have any comments or questions on this or any other real estate related topic, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

Where will YOU sleep tonight?

Over the past few years, I’ve focused this blog on Real Estate Investment Trusts. While I’m NOT backing away from investments in that arena (I still own ACCRE, which is a small REIT fund-of-funds), I am presently focusing more of my attention on housing. Where most of us sleep at night comes in several different varieties – single family detached homes, owner-occupied condominiums and other attached housing, rental homes and condos, and of course rental apartments.

According to the most recent statistics I have, there were about 145.3 million ‘housing units’ in America as of July 1, 2023, or about 1 for every 2.3 people. Of the occupied units, about 65.8% are ‘owner occupied’ (both single-family and attached), while the remainder are some sort of rental units, such as single family rental houses or apartments. Over the past couple of years, we’ve seen an increase in housing units of about 1% per year, more or less. That’s about two to three times the rate of growth in the population, so… sounds like everything’s OK, right?

Yet, there is enormous angst about housing availability and affordability in all corners. At the low end of the economic spectrum, about 1.25 million people experienced homelessness a some point in 2020, the last year for which HUD has published data (according to the US Government’s Interagency Council on Homelessness). As we move up the economic ladder, the working poor, when they can find housing, are forced to pay increasingly large portions of their budget for shelter, thus crowding out food, health care, and other necessities of life. Even the so-called ‘middle class’, if you can still call it that, find homeownership prohibitive.

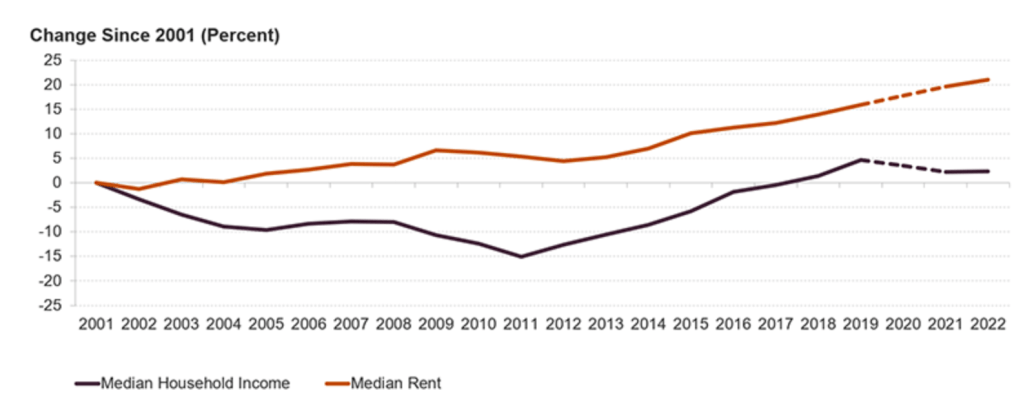

Most pundits (and I’m citing CNBC here) tell us that as a general rule, the total cost of housing (rent or mortgage payment plus utilities) should be no more than 30% of the household’s budget. Ironically, renters, who are often the ones who cannot afford home ownership, seem to have it worse. As of the 2021 American Housing Survey, over 50% of renters report paying over that 30% threshold. When broken down by income level, about 64% of households earning less than $50,000 per year report paying over the 30% benchmark. According to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, rent has increased over 20% since 2001 even after accounting for inflation, while median household income is virtually unchanged.

For those trying to join the ranks of homeownership, the story is even worse. Taking the longer view, in 1985, the median household income in America was $22,400, and the median home price was $78,200, for a ratio of 3.5. Even back then, steep interest rates consumed nearly half of a typical household income in mortgage payments. Today, in America, with lower interest rates fueling a housing demand, the median sales price of a dwelling is $433,100, and the median household income is $74,600, resulting in a ratio of 5.8.

Wells Fargo and the National Association of Homebuilders conduct an annual survey of homebuilder sentiment, which is a weighted average of current housing starts, anticipated starts over the next 6 months, and ‘buyer traffic’, which is essentially a measure of buyer interest in new homes. As of October, 2024, the index stood at 43, which for the sake of comparison, is about where it stood in the middle of the 2008-10 housing crash. Not surprisingly, housing starts right now are only 992,000 per year, about where it stood 40 years ago.

Many buyers and apartment developers blame interest rates, but that’s only part of the story. Costs have skyrocketed all across the nation, not just ‘hard costs’ (sticks, bricks, and labor) but also ‘soft costs’ such as regulatory burdens, permitting fees, and marketing costs. In the ‘hottest’ areas – the places where people want to live – the cost of land has also become burdensome. Forty years ago, merchant builders considered land should cost between 30% and 40% of the selling price of a single family dwelling. Today, in the top markets, that number can exceed 50% or more.

Over the course of the next few weeks and months, I’m going to explore some of these issues in more detail. As always, if you have any specific questions or comments, please let me know.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

S&P Case Shiller Report

I WISH I could be excited about the most recent home price index report. I really wish I could.

The news is mediocre, at best — home prices in April rose by 1.3% on average from their record lows in March, and are still down 2.2% (for the 10-city composite) from April, 2011. Not surprisingly (after March’s terrible news), no cities posted new lows in April. Of the 20 cities tracked, 18 showed increases (NYC and Detroit being the exceptions).

So, why? If you read my blog yesterday, you know we have a terrifically supply-constrained market. This morning’s Wall Street Journal had an article about Chinese investors who are providing about $1.8 Billion in kick-start capital to Lennar to get a big 12,000+ home community underway in San Francisco — a project Lennar has been working on for 9 years. While I congratulate the Chinese and Lennar for this partnership, it does not at all bode well for U.S. investment liquiity that off-shore capital is needed to get a new project off the ground in one of America’s most dynamic cities.

Recall from ECON 101 that “price” is what happens at equilibrium when supply intersects with demand. (OK, technically “price” can emerge in disequilibrium, as well.) Right now, supply is hugely constrained, with a lot of REO-overhang and little new construction. If demand was healthy and growing, prices should be soaring. Instead, prices remain flat-lined, suggesting that demand is also stagnant. However, population continues to grow and household formation should be positive.

What’s taking up the slack? The apartment market continues to explode, with huge demand for rental units. What’s the end game for all of this? I can only think of two results:

1. The home ownership rate in America continues to languish, finding some new post-WW II low; or

2. Eventually, home ownership will go on the rise, and we’ll have an overbuilt situation in apartments.

Where would I bet? Sadly, given the state of the world’s economy, #1 looks more tenable in the long-term. That doesn’t mean we’re moving from being a nation of home owners to a nation of renters, but it does mean that the tradition of home ownership which has prevailed in the U.S. for decades may be becoming passe. Either way, in the intermediate term (the next several years), we’re probably looking at the status quo.

Latest from S&P Case Shiller

The always excellent S&P Case Shiller report came out this morning, followed by a teleconference with Professors Carl Case and Bob Shiller. First, some highlights from the report, then some blurbs from the teleconference.

The average home prices in the U.S. are hovering around record lows as measured from their peaks in December, 2006, and have been bounding around 2003 prices for about 3 years. Overall in 2011, prices were down about 4% nationwide, and in the 20 leading cities in the U.S., the yearly price trends ranged from a low of -12.8% in Atlanta to a high (if you can call it that) of 0.5% in (amazingly enough) Detroit, which was the only major city to record positive numbers last year. In December, only Phoenix and Miami were on up-tics.

The average home prices in the U.S. are hovering around record lows as measured from their peaks in December, 2006, and have been bounding around 2003 prices for about 3 years. Overall in 2011, prices were down about 4% nationwide, and in the 20 leading cities in the U.S., the yearly price trends ranged from a low of -12.8% in Atlanta to a high (if you can call it that) of 0.5% in (amazingly enough) Detroit, which was the only major city to record positive numbers last year. In December, only Phoenix and Miami were on up-tics.

One thing struck me as a bit foreboding in the report. While housing doesn’t behave like securitized assets, housing markets are, in fact, influenced by many of the same forces. Historically, one of the big differences was that house prices were always believed to trend positively in the long run, so “bear” markets didn’t really exist in housing. (More on that in a minute). With that in mind, though, w-a-a-y back in my Wall Street days (a LONG time ago!), technical traders — as they were known back then — would have recognized the pricing behavior over the past few quarters as a “head-and-shoulders” pattern. It was the mark of a stock price that kept trying to burst through a resistance level, but couldn’t sustain the momentum. After three such tries, it would collapse due to lack of buyers. I look at the house price performance, and… well… one has to wonder…

One thing struck me as a bit foreboding in the report. While housing doesn’t behave like securitized assets, housing markets are, in fact, influenced by many of the same forces. Historically, one of the big differences was that house prices were always believed to trend positively in the long run, so “bear” markets didn’t really exist in housing. (More on that in a minute). With that in mind, though, w-a-a-y back in my Wall Street days (a LONG time ago!), technical traders — as they were known back then — would have recognized the pricing behavior over the past few quarters as a “head-and-shoulders” pattern. It was the mark of a stock price that kept trying to burst through a resistance level, but couldn’t sustain the momentum. After three such tries, it would collapse due to lack of buyers. I look at the house price performance, and… well… one has to wonder…

As for the teleconference, the catch-phrase was “nervous but hopeful”. There was much ado about recent positive news from the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (refer to my comments about this on February 15 by clicking here.) The HMI tracks buyer interest, among other things, but the folks at S&P C-S were a bit cautious, noting that sales data doesn’t seem to be responding yet.

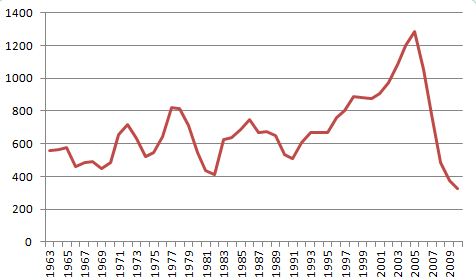

There are important macro-economic implications for all of this. The housing market is the primary tool for the FED to exert economic pressure via interest rates. Historically (and C-S goes back 60 or so years for this), housing starts in America hover around 1 million to 1.5 million per year. If the economy gets overheated, then interest rates can be allowed to rise, and this number would drop BRIEFLY to around 800,000, then bounce back up. However, housing starts have now hovered below 700,000/year every month for the past 40 months, with little let-up in sight.

Existing home sales are, in fact, trending up a bit, but part of this comes from the fact that in California and Florida, two of the hardest-hit states, we find fully 1/3 of the entire nation’s aggregate home values. The demographics in these two states are very different from the rest of the nation — mainly older homeowners who can afford now to trade up.

An additional concern comes from the Census Bureau. Note that for most of recent history, household formation in the U.S. rose from 1 million to 1.5 million per year (note the parallel to housing starts?). However, from March, 2010, to March, 2011, households actually SHRANK. Fortunately, this number seems to be correcting itself, and about 2 million new households were formed between March, 2011, and the end of the year. C-S note that this is a VERY “noisy” number and subject to correction. However, the arrows may be pointed in the right direction again.

Pricing still reflects the huge shadow inventory, but NAR reports that the actual “For Sale” inventory is around normal levels again (about a 6-month supply). So, what’s holding the housing market back? Getting a mortgage is very difficult today without perfect credit — the private mortgage insurance market has completely disappeared. Unemployment is still a problem, and particularly the contagious fear that permeates the populus. Finally, some economists fear that there may actually be a permanent shift in the U.S. market attitude toward housing. Historically, Americans thought that home prices would continuously rise, and hence a home investment was a secure store of value. That attitude may have permanently been damaged.

“Nervous, but hopeful”

The housing market — Damning with faint praise

Sorry we’ve been absent for so long — it’s been a terrifically busy summer and early fall here at Greenfield. Hopefully, we’ll be back in the saddle more frequently for the rest of this year.

From an economist’s perspective, there’s plenty to talk about — Euro-zone debt crisis, job growth (or lack thereof), Federal and state debt, etc., etc., etc. My own focus is the mixed-message on the housing market, which continues in the doldrums. If you listen to the reports from the National Association of Realtors, you get some positive headlines followed by fairly depressing details. Existing home sales are better than forecasted, mainly due to great borrowing rates and the influx of “investor-buyers”. Lots of single family homes and condos are being turned into rental property or held “dark” for the economic lights to come back on. A surprisingly large number of homes are purchased for all-cash, since if you believe that housing prices are near their bottom, then residential real estate may be more stable — and potentially have better returns — than equities.

On the other hand, new home sales continue to languish at their lowest levels since we started keeping score in 1963.

Intriguingly, if you ignore the post-2003 “bubble” period, and trendline the data (which grows over time, to account for the increasing population), you end up with about 900,000 new home sales in 2011. As it happens, we’re actually around 300,000, reflective of a significant decline in home ownership rates — now down to about 66%.

The real question is whether or not this change in home ownership rates is temporary or permanent. We happen to think it’s permanent. That’s not all bad news, but it means that when new home sales come back on-line (eventually getting back to somewhere short of 900,000, but certainly higher than 300,000), we won’t see a return to bubble-statistics.