Archive for the ‘Affordable Housing’ Category

New Home Sales — “Much Ado About Not Enough”

Big news today — new home sales hit an annualized rate of 369,000 in May, compared to 343,000 in April. That’s 20% higher than a year ago. It also beat economists collective prognostications of 350,000.

Wow…. and only about 63% less than the 1,000,000 per year we would consider health.

And about 74% below the peak of 1.4 million during the boom years.

Obviously, there’s a problem here, and unless and until we get back to “normal”, the portion of the economy which is driven by home development, construction, financing, and sales will continue to suffer. Three things are currently terribly broken, and fixing them is no easy task.

1. The lending market is utterly disfunctional. There was a great headline in one of the papers the other day — if you don’t NEED money, there’s plenty of it. Unquestionably, one of the contributing factors (not a major one — but one, none the less) to the market meltdown was the sale and financing of homes to folks who had utterly no idea how they were going to meet their mortgage payments. However, even in good times, we know that a certain percentage of loans will go sour — call it about 2%. The straw that broke the camel’s back was when the recession hit, that “sour loan” percentage went up to about 4% – 6%. Unfortunately, the secondary market had “priced” these loan pools with the notion that only 2% or so would go bad. The loan pools themselves were so badly over-leveraged (at Lehman, apparently, the pools were leveraged something like 35-to-1 or more) that an increase into the 4% range completely destroyed the secondary mortgage market. Today, the pendulum has swung too-far in the other direction, and first-time homebuyers, who often have good jobs but little in the way of demonstrable credit, are completely shut out. If they can’t buy “starter” homes, then the “move-up” market suffers, and the retirees (who want to buy in places like Reno and Ft. Lauderdale) can’t sell their homes to “move down”. Fixing this lending crisis is the first order of business.

2. The land development business is broken. Even if we magically “fixed” the lending problem tomorrow, there is a real shortage of land in the development pipeline. It takes years to turn a vacant field into a subdivision full of lots (or a condo site), with extensive engineering, planning, financing, and entrepreneurship efforts. Even in good years, there is a fair amount of risk-taking and capital expenditure. We can’t just pick up where we left off a few years ago, because many (most? nearly all?) of these development projects burst like soap bubbles during the recession. Thus, we have to completely hit the “re-start” button on subdivision development in America. Unfortunately, there is absolutely no appetite for financing these projects, and many of the players have gone out of business. After World War II, the country was able to kick-start the housing market with extraordinarly favorable financing (remember VA and FHA loans?). None of that exists today, and the secondary market to sustain all of that has gone away. In the absense of a Federal mandate to kick-start housing, comparable to the GI Bill of 1944, this aspect of the market will continue to be flat-lined.

3. Local community infrastructure development is broken. Housing development requires a substantial public-private partnership. In many communities, much of this is paid for as a “public good”, while in others there is the expectation of significant developer contribution. Nevertheless, local planning agencies, transportation and utility departments, and even school districts and fire departments have to stand ready to provide infrastructure for housing. Local government fiscal crises have frequently broken the back of these agencies. Nationally, we’ve laid off something like 50,000 teachers in the past few years, yet new housing development and household formation will require increasing numbers of schools. The same is true for fire fighters, EMTs, police, road maintenance, and utilities. Until our cities, counties, and states are back on their financial feet, this segment of the equation will continue broken

Sadly, these are interactive parts of the same equation. For example, local governments fund planning departments with fees paid by developers. Hence, the city or county reviews tomorrow’s building permits with fees paid by yesterday’s developers. Restarting the system will take talent, money, and some significant leadership, none of which is currently apparent.

Latest from S&P Case Shiller

The always excellent S&P Case Shiller report came out this morning, followed by a teleconference with Professors Carl Case and Bob Shiller. First, some highlights from the report, then some blurbs from the teleconference.

The average home prices in the U.S. are hovering around record lows as measured from their peaks in December, 2006, and have been bounding around 2003 prices for about 3 years. Overall in 2011, prices were down about 4% nationwide, and in the 20 leading cities in the U.S., the yearly price trends ranged from a low of -12.8% in Atlanta to a high (if you can call it that) of 0.5% in (amazingly enough) Detroit, which was the only major city to record positive numbers last year. In December, only Phoenix and Miami were on up-tics.

The average home prices in the U.S. are hovering around record lows as measured from their peaks in December, 2006, and have been bounding around 2003 prices for about 3 years. Overall in 2011, prices were down about 4% nationwide, and in the 20 leading cities in the U.S., the yearly price trends ranged from a low of -12.8% in Atlanta to a high (if you can call it that) of 0.5% in (amazingly enough) Detroit, which was the only major city to record positive numbers last year. In December, only Phoenix and Miami were on up-tics.

One thing struck me as a bit foreboding in the report. While housing doesn’t behave like securitized assets, housing markets are, in fact, influenced by many of the same forces. Historically, one of the big differences was that house prices were always believed to trend positively in the long run, so “bear” markets didn’t really exist in housing. (More on that in a minute). With that in mind, though, w-a-a-y back in my Wall Street days (a LONG time ago!), technical traders — as they were known back then — would have recognized the pricing behavior over the past few quarters as a “head-and-shoulders” pattern. It was the mark of a stock price that kept trying to burst through a resistance level, but couldn’t sustain the momentum. After three such tries, it would collapse due to lack of buyers. I look at the house price performance, and… well… one has to wonder…

One thing struck me as a bit foreboding in the report. While housing doesn’t behave like securitized assets, housing markets are, in fact, influenced by many of the same forces. Historically, one of the big differences was that house prices were always believed to trend positively in the long run, so “bear” markets didn’t really exist in housing. (More on that in a minute). With that in mind, though, w-a-a-y back in my Wall Street days (a LONG time ago!), technical traders — as they were known back then — would have recognized the pricing behavior over the past few quarters as a “head-and-shoulders” pattern. It was the mark of a stock price that kept trying to burst through a resistance level, but couldn’t sustain the momentum. After three such tries, it would collapse due to lack of buyers. I look at the house price performance, and… well… one has to wonder…

As for the teleconference, the catch-phrase was “nervous but hopeful”. There was much ado about recent positive news from the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (refer to my comments about this on February 15 by clicking here.) The HMI tracks buyer interest, among other things, but the folks at S&P C-S were a bit cautious, noting that sales data doesn’t seem to be responding yet.

There are important macro-economic implications for all of this. The housing market is the primary tool for the FED to exert economic pressure via interest rates. Historically (and C-S goes back 60 or so years for this), housing starts in America hover around 1 million to 1.5 million per year. If the economy gets overheated, then interest rates can be allowed to rise, and this number would drop BRIEFLY to around 800,000, then bounce back up. However, housing starts have now hovered below 700,000/year every month for the past 40 months, with little let-up in sight.

Existing home sales are, in fact, trending up a bit, but part of this comes from the fact that in California and Florida, two of the hardest-hit states, we find fully 1/3 of the entire nation’s aggregate home values. The demographics in these two states are very different from the rest of the nation — mainly older homeowners who can afford now to trade up.

An additional concern comes from the Census Bureau. Note that for most of recent history, household formation in the U.S. rose from 1 million to 1.5 million per year (note the parallel to housing starts?). However, from March, 2010, to March, 2011, households actually SHRANK. Fortunately, this number seems to be correcting itself, and about 2 million new households were formed between March, 2011, and the end of the year. C-S note that this is a VERY “noisy” number and subject to correction. However, the arrows may be pointed in the right direction again.

Pricing still reflects the huge shadow inventory, but NAR reports that the actual “For Sale” inventory is around normal levels again (about a 6-month supply). So, what’s holding the housing market back? Getting a mortgage is very difficult today without perfect credit — the private mortgage insurance market has completely disappeared. Unemployment is still a problem, and particularly the contagious fear that permeates the populus. Finally, some economists fear that there may actually be a permanent shift in the U.S. market attitude toward housing. Historically, Americans thought that home prices would continuously rise, and hence a home investment was a secure store of value. That attitude may have permanently been damaged.

“Nervous, but hopeful”

U.S. housing market — good news and bad

The good news, such that it is — home sales are inching up — a 0.7% rise in January from the previous January.

Now, for the bad news — the median home price in America, measured on a January-to-January basis, just hit its lowest point in 10 years, according to a recent announcement from the National Association of Realtors. Indeed, 35% of home sales were “distress sales”, driving the median home price down to $154,000.

This represents a 6.9% price decline from 2011, and a drop of 29.4% since the peak in 2007.

Housing News

I was just at a luncheon (sponsored by the local chapter of the Appraisal Institute) on apartments. One of the speakers noted that a real problem in doing adequate analysis was getting a handle on the single-family housing market — the data simply stinks due to the foreclosure mess, the number of homes being turned into rentals, etc. Thus, as we try to ALSO project the future of the homebuilding industry (really down for the count the last few years), that same dirty-data problem is a real issue.

That aside, the National Association of Homebuilders released a report today noting that the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index rose in February for the fifth consecutive month. As I discussed back in November (click here for a link) this index attempt to project home sales based on model home traffic, customer inquiries, and such. Even though the over all stock market was down today, this news sent homebuilder prices higher — indeed, Beazer Homes (BZH) rose by 3.1%, albeit to just over $3/share.

NAHB’s Chief Economist David Crowe said, “this is the longest period of sustained improvement we have seen in the HMI since 2007.” Great news for homebuilders — we hope it stays this way. For a full copy of the article, on Fox Business News, click here.

Proposals for fixing housing

John K. McIlwain is the Senior Resident Fellow/J. Ronald Terwilliger Chair for Housing at the Urban Land Institute (ULI) in Washington, D.C. I don’t necessarily agree with everything he says, but he stimulates some interesting thinking in a piece this week titled “Fixing the Housing Markets: Three Proposals“. (click on the title to link to the article itself.)

In summary, he proposes:

1. Renting federally held REO

2. Creating a mortgage interest credit

3. Divide mortgages for underwater homeowners into a “paying” first and a “delayed” second.

He admits that in the current political climate, none of the above stands a ghost of a chance (nor would any other solution, good or bad), but even though I might disagree with some of what he says, I’m a firm believer in the old In Search of Excellence adage: ready, shoot, aim. Really excellent organizations (and government entities — which are rarely even CLOSE to achieving excellence) have a proclivity for doing SOMETHING. The Marine Corps calls it the “70% solution”, which dictates that you attack as soon as you think you have 70% of the information needed for success. Why not 100%? Because fate favors the side with the initiative and momentum, that’s why.

So, please indulge me for a moment to comment on McIlwain’s proposals, but DON’T take my criticism as an indication that I wouldn’t vote in favor of doing exactly what he proposes, because in the current climate, a half-good idea is probably better than no idea at all.

1. Rent federally held REO — Well, even McIlwain admits (or at least implies) that the government is a terrible landlord, so he would propose turning this over to the private sector via pools of “privatized” REOs. What he’s essentially saying is to sell these REO’s (currently about 250,000, and expected to grow to a million) to investors with the caveats that they be held off the market as rentals for a period of time, AND that there be adequate maintenance to keep them from turning into slums.

My ONE disagreement with this is that less government involvement is usually better than MORE. Plenty of investors stand ready to buy REOs right now, and the resale market is sufficiently poor that these investors recognize they have to be in it for the long haul. Local planning ordinances are usually adequate vis-a-vis slum prevention IF they are enforced properly (as is not always the case). There is no reason to believe that additional Federal caveats would improve the situation. In short, this is actually being accomplished already, and deserves facilitation by the government, not regulation.

2. Mortgage interest credit — McIlwain notes, and we concur, that the current mortgage interest deduction benefits taxpayers earning over $100,000, but hardly those earning less. He suggests replacing this with a flat 15% tax credit, which would have the double-barrelled effect of raising the effective tax rate on those earning over the 15% marginal break-point, but directly benefitting dollar-for-dollar those below that break point. It’s an intriguing idea, but would require the Realtors’ and Mortgage Bankers’ buy-in. In today’s troubled market, it’s difficult to see how they would agree to anything that tinkers with the status quo.

3. Divide mortgages for underwater homeowners into a “paying” first and a “delayed” second. As much as I like this one on the surface, it ONLY works for homeowners who plan to stay in their houses until prices rise (on average) about 20%. We don’t see that happening for quite a few years, so this essentially just kicks the can down the road a bit. Even that, though, is an improvement over the status quo, and keeps homeowners in their homes for the time being. The real problem, of course, is how to deal with the “delayed” paper on banks books.

In short, McIlwain’s proposals at least stimulate some conversation about solutions for the terrific vacant REO problem. One big issue is lack of credit for suitable property managers — banks are loathe to loan on “second” homes today, and investment property (REOs turned into rental homes) is a troublesome loan to get. I would propose that the agencies/banks holding paper on vacant homes simply privatize it immediately — if a bank holds a $100,000 loan on a vacant house, then a reasonably creditworthy investor who is willing to start amortizing that loan should be able to walk in, pick up the keys, and walk out the door. Sure, this would violate all sorts of down-payment caveats in place right now, but it would get interest payments moving again, provide much-needed rental housing, and get some local entrepreneurs busy managing otherwise dead assets.

Musings about the real estate market — part 1

When we say the “real estate market” we’re really talking about four distinct but somewhat inter-related components: housing sales (and values), housing finance, commercial real estate (starts, occupancy, etc.), and commercial finance. Each of these components has plenty of sub-groupings. For example, commercial apartment development is going well, although commercial apartment finance still has some problems. Housing development finance is on life support. Many aspects of commercial development (e.g. – hotels) are moribund.

I’ll start today with the most significant problem in the housing sector — the one which may take the longest to fix — and that’s housing starts. The market is worse than it’s been since we’ve been tracking data (40+ years) and certainly the worst in my experience. The attached graphic comes from the National Association of Homebuilders, and shows their tracking of both housing starts as well as the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (HMI).

The HMI is based on a survey of current new home sales, prospective sales in the next six months, and “traffic” of prospective buyers (seasonally adjusted). While the two graphs seem to track one another, as you can see, the HMI is a bit of a leading indicator of the direction of housing starts. On a historic basis, this makes sense, since homebuilders will “start” houses they think will be sold six months from now, and they will heuristically base that on traffic from prospective buyers. (Back when I was in the game, we talked about a “qualified buying unit” being a prospective buyer or housing unit — such as a family — who actually had the capacity to buy a home and were actively in the market for a new home.)

The HMI is based on a survey of current new home sales, prospective sales in the next six months, and “traffic” of prospective buyers (seasonally adjusted). While the two graphs seem to track one another, as you can see, the HMI is a bit of a leading indicator of the direction of housing starts. On a historic basis, this makes sense, since homebuilders will “start” houses they think will be sold six months from now, and they will heuristically base that on traffic from prospective buyers. (Back when I was in the game, we talked about a “qualified buying unit” being a prospective buyer or housing unit — such as a family — who actually had the capacity to buy a home and were actively in the market for a new home.)

As you can see, back during a period of relative housing stability (1985 – 2005), housing starts generally cycled between 1 million and 1.4 millin per year. With the bubble in home ownership rates, starts got up to 1.8 million for a short period then collapsed. More interestingly is the period between 1989 and 1993, when home starts dipped to about 600,000 per year, then rapidly bounced back to a healthy level. That was a period marked by real problems with acquisition, development and construction (ADC) loans, but the underlying demand and value equations still held firm. Thus, when the market cleared (when demand sapped up any supply overhang), the homebuilding community was ready to go back to work.

Today, it’s VERY different. ADC lending is still nearly non-existent (compared to a half-decade ago). The decline in values means that in many markets, it’s difficult to build a home for less than the selling prices. Further, the permanent lending market is also problematic. A big chunk of homebuilding is the “move-up” market, with a secondary chunk in the vacation or second-home market. Down payments for “move-ups” and second-homes traditionally come from equity in existing homes. However, a substantial proportion of homes in America have no net-equity. Reports talk about the high percentage of homes which are “under water” (that is, the value is less than the mortgage. However, for a home to have positive “net equity”, the value needs to exceed both the mortgage as well as anticipated selling costs. A handy rule-of-thumb in many markets is that a home needs to be valued around 110% of the mortgage for a seller just to break even on a sale. Worse, for there to be sufficient equity to “move up”, the home needs to be valued more like 120% to 130% of the mortgage. That simply doesn’t exist in most of America right now — trillions of dollars in paper equity disappeared over the past few years.

Additionally, there is a huge overhang in shadow inventory. As I noted in a recent blog post, Americans are currently buying under 5 million homes per year (new plus re-sale) and in a healthy market, the inventory for sale is about a six-month supply. However, the shadow inventory alone is close to 6 million right now (and that doesn’t include “regular” homes on the market). Thus, we’re looking at a couple of years of absorption just to get the market back to some level of stability. Even THAT presumes that the home ownership rate will stabilize right where it is (it’s been falling precipitously for several years). Bottom line, I wouldn’t be betting on home construction any time in the near future.

This is important for several reasons. First, home construction is a very big chunk of the economy. When homes aren’t getting built, lots of carpenters, plumbers, electricians, materials suppliers, real estate agents, bulldozer operators, bricklayers, and such don’t have work. Second, these are skills which are being lost to the economy. Further, if America is going to get the employment picture fixed, these people have to get back to work.

Good news — such as it is — is that the HMI is trending upward, ever so slightly. It’s currently standing at 20, up from a bottom below 10 about 3 years ago (and a near-term bottom of about 15 earlier this year). It needs to bounce all the way back up in the 50 range if the leading-indicator relationship holds true for it to point toward a healthy housing market. It actually went that far in the 1991 – 1993, range, when it bounced from 20 to 70 in about 3 years. However, that was a market with pent-up demand, good values, and a healthier lending climate.

The housing market — Damning with faint praise

Sorry we’ve been absent for so long — it’s been a terrifically busy summer and early fall here at Greenfield. Hopefully, we’ll be back in the saddle more frequently for the rest of this year.

From an economist’s perspective, there’s plenty to talk about — Euro-zone debt crisis, job growth (or lack thereof), Federal and state debt, etc., etc., etc. My own focus is the mixed-message on the housing market, which continues in the doldrums. If you listen to the reports from the National Association of Realtors, you get some positive headlines followed by fairly depressing details. Existing home sales are better than forecasted, mainly due to great borrowing rates and the influx of “investor-buyers”. Lots of single family homes and condos are being turned into rental property or held “dark” for the economic lights to come back on. A surprisingly large number of homes are purchased for all-cash, since if you believe that housing prices are near their bottom, then residential real estate may be more stable — and potentially have better returns — than equities.

On the other hand, new home sales continue to languish at their lowest levels since we started keeping score in 1963.

Intriguingly, if you ignore the post-2003 “bubble” period, and trendline the data (which grows over time, to account for the increasing population), you end up with about 900,000 new home sales in 2011. As it happens, we’re actually around 300,000, reflective of a significant decline in home ownership rates — now down to about 66%.

The real question is whether or not this change in home ownership rates is temporary or permanent. We happen to think it’s permanent. That’s not all bad news, but it means that when new home sales come back on-line (eventually getting back to somewhere short of 900,000, but certainly higher than 300,000), we won’t see a return to bubble-statistics.

Housing — and today’s WSJ

The front page of the Wall Street Journal today is plastered with the story of the continued problems with house prices, courtesy of info from the S&P-Case Shiller Index. I’ve commented on this several times before in this blog, but it bears further investigation.

Prior post-WWII real estate recessions (if we can call them that) have been quickly self-correcting. Stagnation in house prices lead to increased investment, as buyers look for deals and bankers need to make loans. As such, real estate recessions rarely have actual price declines, but instead are marked with volume slow-downs or price stagnation.

This recession is very different. Bankers are highly reluctant to make loans, in stark contrast to prior recession-exits. Regulatory problems, lack of bank capital, a doubling of REO portfolios, lack of cash from retail buyers, and a real fear (by both bankers and buyers) that collateral values will continue to decline puts the market in a continued downward spiral. To make matters worse, since many owner/sellers (particularly the most fragile ones — in the “zero down payment” starter homes) are themselves faced with economic travail and often the need to move to find work, the potential for further foreclosures down-the-road is very real, thus further driving down prices. Add to this the fact that a very big chuck of the U.S. economy is housing-related (contractors, developers, bankers, realtors, and many other intermediaries), it’s easy to see that a sustainable jobs market is hard to envision without “fixing” the housing problem.

We can re-examine the causes of this crisis over and over, but very few analysts are focused on the cure. Pilots are taught that when airplanes stall and go into a spin or a downward spiral, after “pulling the power” the pilot has to do something that’s rather counter-intuitive: point the nose downward and actually fly INTO the stall to get out of it. It’s like steering a car INTO the skid on an icy road. It’s very counter-intuitive, but it’s necessary. (The “black box” — it’s actually orange — recently recovered from the Air France 447 crash showed that the two very junior co-pilots who were at the controls when the plane went into a stall tried to pull BACK on the stick, when they should have pushed FORWARD. If they’d thought back to “Flying 101” they might be alive today.)

The “thing missing” from today’s market is the national policy in favor of affordable housing, which was manifested through Fannie-Mae and Freddie-Mac. Pulling the plug on the secondary market (which was at the core of the housing bubble) basically took our financial markets out of the housing business. Now that the price-bubble has bursts, our financial markets need to step back up to the plate and provide some liquidity. Admittedly, a “fixed” market will need to provide better risk-measures and possibly some hedging tools, but these are details that can be worked out once we get the plane flying again. I hate to say this — I’m generally a “free-market” kinda libertarian guy — but the government will need to step up to the plate as a guarantor of last resort…. and yes, I know the U.S. government is effectively broke. However, until it gets the housing market back on its feet, it’s going to stay broke. At some point, they need to steer the car into the skid.

The death of the fixed rate mortgage

It might also be called the “death of the easy mortgage”, and will almost certainly be the death of the small-town lender….

The Obama Administration today outlined the broad-stroke strategy for dealing with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They suggest three solutions, all of which basically call for a multi-year wind-down of the two troubled institutions, which have cost taxpayers about $150 Billion in recent years to bail out.

How we got this way has been covered in thousands of articles, blog posts, and even text books. FNMA and FHLMC were set up to provide liquidity to small mortgage lenders (primarily, small-town S&L’s, of which there aren’t many now-a-days). A small-town S&L had a fairly finite pool of deposits, and once they made a few home loans (which were very long in duration), they simply couldn’t loan anymore until those mortgages were paid-off. Worse still, in times of rapidly changing interest rates, low-rate, fixed-rate mortgages didn’t get paid off, but depositors ran for higher-rate money funds. S&L’s were caught in a liquidity trap, and crisis after crisis ensued.

Today, of course, the mortgage lending business is filled with several thosand-pound gorillas with names like Wells Fargo, BofA, and JPMorgan/Chase. These institutions have the muscle to package mortgage pools and sell them off to investors. Why, then, do we have/need FNMA and FHLMC?

Congress is firmly on the hook for this one. Over the past decade and a half, the F’s were encouraged by Congress to morph into investors of last resort for mortgages that the securities market didn’t want. (It was actually a lot more complicated than that, but you get the general picture, right?) Why didn’t the private sector want these mortgages? Because they knew eventually many of them would go bad — and they did. Congress essentially got what it wanted, a subsidy of home ownership which, unfortunately, wasn’t sustainable.

This deal isn’t done yet, of course. Wait for the long-knives to come out from the Realtors and Home Builder’s lobbies. The current proposal would privatize all housing lending with the exception of FHA/VA lending. To put this in a bit of perspective, today, FHA loans constitute over 50% of housing lending. Back in the “hey-day” of the liquidity run-up, FHA loans were down around 4%. Without the F’s, we’re looking at a privatized mortgage market not far different from what we see out there right now, and that’s fairly unsustainable for the homebuilding industry.

Tis the season….

Intriguing mixed messages from the economy. Employment continues to lag, but holiday shopping was up. Go figure?

Two or three things may be in store. First, I’m sure that some of the more profitable businesses, fearing future tax increases, were holding off spending tax-deductable money until 2011 rather than 2010. The key lesson for lawmakers — get some stability and predictability into the tax system.

Second, while “on-line” shopping went up, the unmeasured impact of on-line was the ability to target shopping. Lots of holiday shopping went at bargain prices, and I’m interested to see how much sustainability there will be in the increases. It’s very difficult to imagine, with the underlying instability in economic fundamentals, just how long the shopping bubble can be sustained.

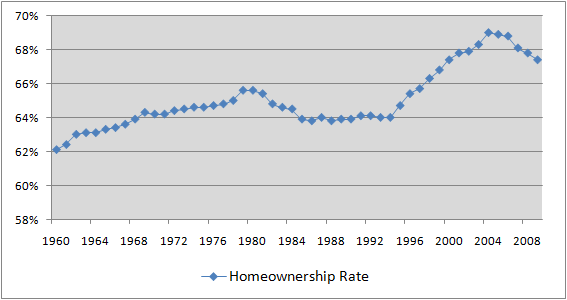

But, on to real estate. What looks good right about now? What looks bad? We continue to be doom-sayers on housing construction into 2011. Normally, in a recession, there’s a build-up of excess supply (construction in the pipeline pre-recession get unsold DURING the recession). However, past recessions rarely have a contemporaneous melt-down in homeownership rates (see the following).

Note that since we began keeping records in 1960, ownership rates have inexorably trended upward but for two instances — this one and the 1980-84 period. After 1984, it took until the mid-1990’s for rates to start trending upward again, and many would suggest that this up-trend was only the result of Greenspan’s “easy money” policies. In a more cautious lending environment, it’s hard to say where the true equilibrium might lie. However, it’s intriguing that the run-up in the 1970’s is often blamed on the high levels of inflation (making home ownership the favored “inflation hedge” for families) and that in the post-recession, low-inflation period of the late 80’s and early 90’s, rates seemed to hover around 64%.

If in fact that’s where the equilibrium lies, then the U.S. has about three more percentage points in owner-occupied homes to absorb. This absorption occurs in one of three ways — growth in the population, conversion of homes to other uses (usually rental in lower-end or transitional neighborhoods), or demolition. Whatever the reason, with the current slope of the trend-line (which, intriguingly, matches the slope of the 1980-84 period), we see that it took about 5 years (2004 through 2009) to get from about 69% to about 67%. At this rate, getting to 64% will take another 7 – 8 years, suggesting a best case scenario of stability in the 2016 range.

This scenario, interestingly enough, matches some of the employment-growth scenarios I’ve seen, which suggest we’re looking at the mid-to-late teens for unemployment to get back down to pre-recession levels.

So, if owner-occupied housing stinks, what looks good on the menu? Apartments. In very rough numbers, we WERE building about 1.5 million homes per year prior to the recession (year-in, year-out, with a HUGE amount of variance from year to year). Now-a-days, we’re building about a third of that or less, suggesting an un-met demand for housing of about a million units per year, more or less. Apartment construction also flat-lined during the recession, primarily because banks simply didn’t have the money to lend for construction financing. (Permanent money comes from other sources, and it’s available, but the construction financing problem is still with us.)

As credit continues to ease — particularly with the recent announcements by the FED in that regard — we can see some strong lights at the end of that tunnel. Good news for construction workers — their unemployment rates have been huge lately, but the same folks who drive nails for owner-occupied homes can also drive nails in apartment complexes. Easing credit in this area will thus fuel job growth, which also fuels consumption, home purchases, etc. Thus, addressing the housing demand/supply problem may be the most important single thing policy makers can do to restore the economy to good health.