Posts Tagged ‘Real Estate’

Some Thoughts on Housing Crisis

Last month, I had the very real pleasure of delivering a major, hour-long address at a conference in Charleston, South Carolina, on the nation’s housing crisis. In it, I discussed the overarching problem and some potential solutions, as well as some problematic ideas which are being bandied about. I’ll synopsize here today.

Right now, we have about 131.5 million households in America, a number which has been growing steadily almost without a break since WW-2. Right now, we ad about one and a quarter million households to that total each year. About two-thirds of us live in owner-occupied dwellings, a number which has remained constant for most of my lifetime.

Just focusing for a moment on the owner-occupied sector, median house prices have gone up about 317% since 1991. However, median household income has increased only about 167%. Over the past three decades, owner-occupied housing has only appeared to be affordable most of the time because (1) we had a sub-prime bubble with artificially easy money in the 1990’s, and then (2) we had very easy money – in fact, a liquidity flood — following the meltdown, and then (3) we have had extremely low interest rates until just a couple of years ago. Owner-occupied demand spiked during the recession, and as everyone knows, cheap money disappeared. Those of us with long memories recognized that today’s supposedly high interest rates were actually the norm a few decades ago. If the FED target of 2% inflation is achieved, it is still very hard to imagine mortgage interest rates coming down much below 5%.

In a reasonably efficient economy, home prices rising would stimulate homebuilders to flood the market with new product. However, a new home is the nexus of several different inputs – materials, skilled labor, land, and ‘soft costs’ (insurance, permits, mitigation fees, taxes, fees, etc.). Unfortunately, these inputs have all been problematic. Material, land, and soft costs have all risen rapidly, and skilled labor is in short supply. In many ways, builders are in worse shape than their customers.

In 2020, the Goldman Sachs housing affordability index stood at 135%, which meant that a median household had 135% of the income necessary to ‘afford’ payments on a typical 30-year conventional mortgage (with 20% down) on a median priced dwelling. Today that index stands at 70%. It is widely agreed that getting that index back up above 100% will be a herculean task.

By the way, what do we mean by ‘affordable’? In general, the total housing burden shouldn’t exceed 30% of a household’s take-home income. What do we mean by ‘housing burden’? For a homeowner, that includes payments on the mortgage (principal and interest), plus homeowner’s insurance and property taxes. Not only have mortgage interest rates soared in recent years, but also, we’ve seen insurance and property tax rates climb at above-inflation rates. While mortgage interest rates may come down in the near future, higher insurance and tax rates may be with us permanently. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that those will actually continue to significantly increase, particularly in hard-hit areas like California and Florida.

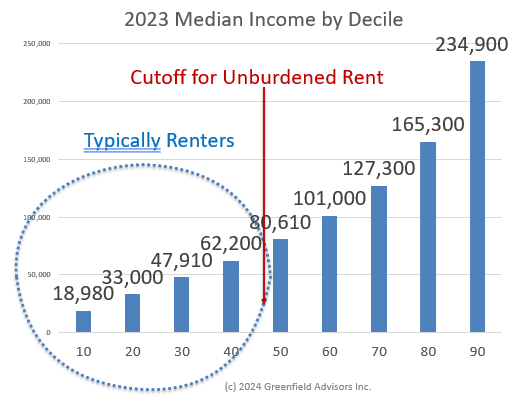

Amazingly, the rental community – about two-thirds of American households – have actually been hit worse. Note that as a general rule of thumb, renters come from the lower deciles of the income strata. Right now, the median household income in America sits at about $80,000 per year. However, the median income for the 40th percentile of Americans is only about $62,600. In other words – and this is a very rough approximation – about 40% of American households make less than about $62,200 per year. And remember, these households are more likely to be renters.

Right now, the median apartment rent in America is $1,595 per month. (The median rent on a single family detached dwelling is $2,000). Add to that about $300 per month for utilities and such, multiply by 12, divide by 30% (the threshold for ‘unburdened’ rent) and you get a household income of $75,800 per year to be considered ‘unburdened’ renting a median apartment in America. And remember, that’s a median, so fully half of the apartments in America are unaffordable for households making $75,800 per year.

Nobody in the bottom 40% of households makes that much money.

Indeed, an estimated 20 million households in America spend over 50% of their income on housing.

So how do we address these problems? We have two major sources of aid for low-income housing. First, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program provides indirect Federal support in the form of tax credits for developers of affordable housing. This program was created out of the 1986 Tax Reform Act, and until 2016 was responsible for building about 115,000 affordable units per year. However, since 2016, for a variety of reasons, the program has only helped finance about 75,000 units per year. As a result of this, in most of the country, we have fewer than 45 affordable and available units for every 100 low-income families, and in the hardest hit states, such as California, Florida, Virginia, and my home state of Washington, the number is under 30 units.

The other major source is the Section 8 voucher system. Funded by the Federal Government through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), but administered by local governments, this program provides full or partial rental vouchers for needy families earning less than 50% of local median income. However, the wait times for a voucher are awful (averaging 28 months nationwide) and only about one in four eligible households ever receive anything.

David Holt, the Republican Mayor of Oklahoma City, speaking on TV talk shows this weekend in his role with the national mayor’s association, noted widespread agreement among the country’s mayors that housing availability and affordability was their number one concern right now. So, what can we do to fix the problem.

Three ‘fixes’ come to mind immediately. First, a bipartisan group of both Senators and Congressional representatives have co-sponsored the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act (Senate bill 1557 and House Resolution 3238). This bill would fix some of the long-standing problems in the program and increase credits overall by 50%. However, the bill is currently stagnating in committee, and even though it has some powerful sponsors, it is simply not at the top of anyone’s agenda right now.

Second, some expansion of the Section 8 program is long overdue. However, the incoming administration is all in favor of massive belt-tightening. In the case of Section 8, this is woefully shortsighted, as the economic problems caused by unaffordable housing far outweigh the cost of this program. However, the attitudes on Capitol Hill are decidedly negative.

Finally, I would propose some significant overhaul in the HUD loan program (known back in my boyhood as ‘FHA Loans’). These loans provide Federal insurance – at no cost to the taxpayers – for homebuyers who meet stringent credit requirements. The loans carry extremely low down-payments – very close to zero. In the early 1980’s, when mortgage interest rates were soaring, many states were allowed to use tax exempt bonds to fund state housing finance programs which routed funds into HUD loans. This was a win-win for all concerned, and the economic stimulus of expanded housing construction far outweighed any lost revenue to the Federal coffers. However, the spread between tax-exempt and taxable bonds was somewhat greater back then, and so there was some meaningful leverage to be applied in lowering the mortgage interest rates, particularly for first-time buyers. That said, some kind of program like this, most likely using HUD leadership, would go a long way to breaking the logjam.

There are, unfortunately, some dumb ideas out there. First, a recent RAND study indicates that local governments, despite meaning well, have actually gotten in the way of affordable housing construction. The local restrictions are myriad, but as a result, the cost of building a new, affordable apartment in California, as an example, has risen to about $1 million per unit. This is utterly unsustainable.

Second, the incoming administration has posed the idea of building new homes on Federal land. Time and space will not permit me to list and discuss all of the reasons why this is a bad idea. As examples, however, it constitutes an intolerable wealth-transfer from existing homeowners to new homeowners, it runs afoul of the Federal mandate that any transfer of Federally owned land be at market value, and let’s face it, there is little available Federal land in any of the places where people actually want to live.

Finally, the incoming Administration has made it a priority to re-privatize Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These private sector groups, with the implicit guarantee of the full faith and credit of the US Treasury, are the primary secondary market makers for mortgage loans. During the housing meltdown, they were in effect ‘taken over’ by the U.S. Treasury, under the auspices of the Federal Housing Finance Authority, and now all of their considerable profits flow into the U.S. coffers. Both political parties have agreed that reprivatization is a goal, albeit for different reasons. However, the devil is in the details here, and a slap-dash reprivatization of organizations with combined balance sheets exceeding $4 TRILLION, would, in some estimation, add considerable burden to the current mortgage interest rates.

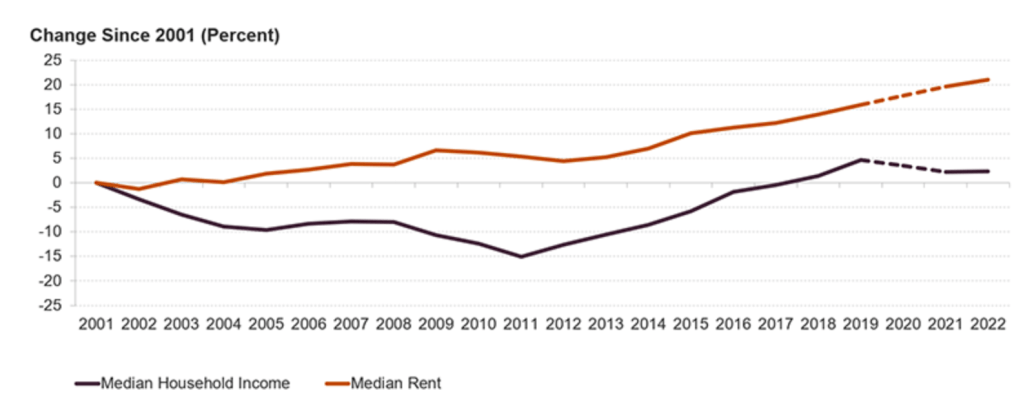

In the end, though, the real crisis is less about housing and more about affordability. In the owner-occupied sector, for example, house prices have been going up, on average about 2% above inflation year-after-year since WW-2. That’s really not a bad thing. It means that home ownership is a really good investment and a nearly perfect hedge against inflation. Even during the housing crisis following 2006-ish, while house prices dipped, they soon reverted to the mean, and today house prices are about where they would have been had the housing crisis never occurred. Over the same post-world war period, household incomes generally also trended upward, more or less, until the 1970’s. However, since then household income has simply failed to keep up with the cost of housing. In short, this current crisis has less to do with the cost of housing and more to do with the stagnating fortunes of middle-class Americans.

As always, if you have any comments or questions on this or any other real estate related topic, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

RAND Study on the Housing Crisis

The RAND Institute, headquartered in Santa Monica, is (in my humble opinion) one of the top-tier sources for research on public policy issues. Founded in 1948 as a partnership between Douglas Aircraft and the Air Force, its founding members included Curtis LeMay and Hap Arnold. The affiliated Pardee Rand graduate school offers a well-regarded Ph.D. in public policy.

Two of the faculty members, economist Jason Ward and Sarah Hunter, a behavioral scientist, recently shared some of their research on the subject. First, they note that interest rates alone have driven up the monthly payment on typical home by as much as 40% over the past 3 years. I would note that this doesn’t factor in the increased cost of the home itself, increasing property taxes and insurance, and increasing costs such as utilities. The Harris campaign has proposed a $25,000 tax credit for first time buyers to assist with down payments. However, a similar pilot-project in California did not fare well and has been linked to driving up the cost of housing in some areas.

Conversely, rent costs have actually moderated a bit very recently, but only because rent growth was so high during and immediately after the pandemic. That said, the RAND researchers noted that a record number of renters are experiencing housing cost burden, that is, a total housing cost above 30% of gross income. Government incentives for renters are a mixed bag. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program provides about $13.5 Billion per year for developers of income restricted, subsidized housing. This program produces about 100,000 housing units per year. However, land use and zoning regulations — a local function — have actually been counterproductive in recent years, with restrictions on multi-family locations, density, energy efficiency, and parking requirements all driving up the cost of solving the housing problem. In much of California, for example, local regulations have driven up the cost of producing an efficiency apartment to nearly $1 million.

The current administration has provided $3.16 Billion to address homelessness, providing funding for over 7,000 local projects to provide housing assistance or support services. Some local governments are also stepping up to the plate. For example, Los Angeles passed a one-quarter cent sales tax in 2017 to fund about $355 million per year for homeless prevention services. This year, they have another measure on the ballot which would provide a $1.2 Billion bond measure to build supportive housing. Houston, Texas, is held up as a model for addressing homelessness with a housing-first approach. As a result, the Houston region has reduced homelessness by 63% over the past 10 years, with an emphasis on coordination across agencies.

Their research continues, and I’m reaching out to Professors Ward and Hunter in the coming weeks as I prepare for a talk I’m giving on this subject in late December. I’ll continue reviewing some of the issues and current research on the complex housing crisis we face in America, with an eye toward finding some consensus on steps forward to solve these issues and share my findings with you as I go along. As always, if you have any comments or questions on this or any other real estate related topic, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

Where will YOU sleep tonight?

Over the past few years, I’ve focused this blog on Real Estate Investment Trusts. While I’m NOT backing away from investments in that arena (I still own ACCRE, which is a small REIT fund-of-funds), I am presently focusing more of my attention on housing. Where most of us sleep at night comes in several different varieties – single family detached homes, owner-occupied condominiums and other attached housing, rental homes and condos, and of course rental apartments.

According to the most recent statistics I have, there were about 145.3 million ‘housing units’ in America as of July 1, 2023, or about 1 for every 2.3 people. Of the occupied units, about 65.8% are ‘owner occupied’ (both single-family and attached), while the remainder are some sort of rental units, such as single family rental houses or apartments. Over the past couple of years, we’ve seen an increase in housing units of about 1% per year, more or less. That’s about two to three times the rate of growth in the population, so… sounds like everything’s OK, right?

Yet, there is enormous angst about housing availability and affordability in all corners. At the low end of the economic spectrum, about 1.25 million people experienced homelessness a some point in 2020, the last year for which HUD has published data (according to the US Government’s Interagency Council on Homelessness). As we move up the economic ladder, the working poor, when they can find housing, are forced to pay increasingly large portions of their budget for shelter, thus crowding out food, health care, and other necessities of life. Even the so-called ‘middle class’, if you can still call it that, find homeownership prohibitive.

Most pundits (and I’m citing CNBC here) tell us that as a general rule, the total cost of housing (rent or mortgage payment plus utilities) should be no more than 30% of the household’s budget. Ironically, renters, who are often the ones who cannot afford home ownership, seem to have it worse. As of the 2021 American Housing Survey, over 50% of renters report paying over that 30% threshold. When broken down by income level, about 64% of households earning less than $50,000 per year report paying over the 30% benchmark. According to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, rent has increased over 20% since 2001 even after accounting for inflation, while median household income is virtually unchanged.

For those trying to join the ranks of homeownership, the story is even worse. Taking the longer view, in 1985, the median household income in America was $22,400, and the median home price was $78,200, for a ratio of 3.5. Even back then, steep interest rates consumed nearly half of a typical household income in mortgage payments. Today, in America, with lower interest rates fueling a housing demand, the median sales price of a dwelling is $433,100, and the median household income is $74,600, resulting in a ratio of 5.8.

Wells Fargo and the National Association of Homebuilders conduct an annual survey of homebuilder sentiment, which is a weighted average of current housing starts, anticipated starts over the next 6 months, and ‘buyer traffic’, which is essentially a measure of buyer interest in new homes. As of October, 2024, the index stood at 43, which for the sake of comparison, is about where it stood in the middle of the 2008-10 housing crash. Not surprisingly, housing starts right now are only 992,000 per year, about where it stood 40 years ago.

Many buyers and apartment developers blame interest rates, but that’s only part of the story. Costs have skyrocketed all across the nation, not just ‘hard costs’ (sticks, bricks, and labor) but also ‘soft costs’ such as regulatory burdens, permitting fees, and marketing costs. In the ‘hottest’ areas – the places where people want to live – the cost of land has also become burdensome. Forty years ago, merchant builders considered land should cost between 30% and 40% of the selling price of a single family dwelling. Today, in the top markets, that number can exceed 50% or more.

Over the course of the next few weeks and months, I’m going to explore some of these issues in more detail. As always, if you have any specific questions or comments, please let me know.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

Are you rich yet?

What a terrible thing to ask, and yet Kiplinger’s tells us that the top 1% of Americans (about 1.3 million households) have a minimum household net worth of about $6 million. Those households control about 23% of all wealth in America. Another block of about 1.3 million households — those between the top 2% and the top 1% — have a minimum household wealth of about $2.5 million, more or less. Of course, these numbers are highly inexact, because… well… I’ll get to that.

By some estimates, real estate makes up as much as 50% of the total net worth for the top 2% of Americans. Again, this is hard to estimate, since typical households don’t have their real estate re-appraised on a daily basis. However, some real estate sectors have done very well, particularly residences, real estate supporting private businesses, and some industrial properties. Before the pandemic, I generally used the VERY heuristic rule of thumb that the super-wealthy (lets say, half a billion net worth and above) had about 25% of their net worth in real estate of some kind or another.

If you’re Jeff Bezos or Warren Buffett or such, you have people who look at this stuff regularly. However, of you’re in one of those 1.3 million households who have a net worth between, say, $2.5 million and $6 million, you probably don’t give it much thought. But maybe you should. I wrote about this in my most recent book, Valuation and Strategy. Here are just a few points, in no particular order:

- Have you considered intergenerational transfers? How exactly will your estate be divided? Is there a way to structure it in an advantageous fashion, considering the often onerous costs of selling property out of an estate?

- Do you own real estate supporting a family business? Is it coupled with the business itself, or is it a separate entity? Do your children or other family members want to continue the business, and do all of them want to participate? Perhaps there are ways to separate the business from the real estate in order to equitably prepare your family members for the inevitable.

- Is any of your real estate financed? What does that look like now? As I write this, interest rates are trending downward after a couple of years at uncomfortable levels. Does this change anything?

- How has your investment real estate changed in value relative to your non-realty investments? Are your asset allocations where you want them to be? Are you comfortable with the risks moving forward?

I would note that the average registered investment advisor is pretty good at not losing you money in the stock market, but ill-prepared to advise on the nuances of real estate investing. That said, most real estate brokers are ill-equipped to advise on wealth management issues. There are people out there who can help you, and with the economy in some flux, now would be a good time to take a long hard look at your real estate holdings.

As always, if you have any questions about this, please don’t hesitate to reach out!

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

12th Fed District issues 3q report

Greenfield is a global firm (albeit mostly in the U.S.), and even though we’re headquartered in Seattle, we try to focus our attention broadly rather than locally. That said, the 12th Federal Reserve District just released First Glance 12L (3Q15) which takes an early cut at the data from the nine western states. It’s very telling data — the “left coast” as I like to call it tends to suffer worse when times are bad and boom better when times are good. Thus, there are some interesting facts and figures to be gleaned from this well-written report.

Naturally, the report is focused on the health of the member banks in the region, but the macro-econ factors driving that health are of much broader importance. Nationally, unemployment stood at 5.1% at the end of the 3rd quarter. Western states tended to be a bit worse off, with 3 states (Idaho, Utah, and Hawaii) recording lower unemployment rates and the rest showing higher numbers, ranging from Washington’s 5.2% up to Nevada’s 6.7%. California, always the thousand pound gorilla in the room, came in at 5.9%.

However, job growth in the western states is well above the national average — 3% annually for the region versus 2% for the U.S. as a whole. However, the west is digging out of a deeper hole — while job growth nationally hit a trough of -4.9% at the peak of the recession, it bottomed out at -6.7% in the west. Generally, job growth in the west over the past 20 years had held steady at about one percentage point above the national trend during “boom” years.

Housing starts in the west are well below the pre-recession peaks. As of September, 2015, the seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of housing starts stood at 161,000, with 107,000 of that in 2+ family units. This compares with a peak of 449,000 SAAR in the 2005-2006 period, at a time when 2+ unit housing only made up 85,000 of the starts. Arguably, the market in the west is still absorbing the huge shadow inventory built up during the boom days.

Commercial vacancy rates in the west have been drifting down for the past few years in the office, industrial, and retail sectors. Apartments, however, seem to have plateaued around 4.3% at the end of the 3rd quarter, and are forecast to rise a bit to 4.7% a year from now. I might posit that historically, profit-maximizing apartment vacancy rates have been found to be somewhat higher than these numbers, so apartment managers and owners may have some lee-way to continue building.

The 5 western maritime states are very export-driven, and the strength of the U.S. dollar (up about 18% against major currencies since 2014) has been rough news for those markets. While western state exports rebounded nicely from the trough of the recession (up about 17% from 2009 to 2010), export growth has flat-lined since 2012. Regionally, exports declined about 2.5% since last year, with positive growth reported in only four states (Arizona, Hawaii, Nevada, and Utah). Bellweather California saw exports decline 3.6%. Note that in Washington, my semi-home state, exports make up 21.2% of the gross state product. (We export things like big trucks, big airplanes, software, and agricultural products.) Hence, this is critically important stuff.

The remainder of the report focuses on the health of the regions banks. I’ll leave that up to the reader if you care to download your own copy. Short answer, though, is that the region has seen loan growth accelerate even while the nation as a whole has flattened. Further, the regions banks tend to be a bit more efficient in terms of expenses and staff, both compared to the nation as a whole and compared to the “boom days” pre-recession. Both small and large commercial borrowers generally reported tightening credit standards at the end of the 3rd quarter, which is a change from previous reports. However, consumer borrowers (residential mortgage, credit cards, and auto loans) generally reported easier standards. The bulk of loan growth for small banks (under $10B) came from non-farm non-residential, while for large banks the biggest growth sector was in consumer lending. The percentage non-performing assets (the “Texas Ratio”) in the region, which peaked at 38.9% in 2009, is now down to 5.4%, although still higher than in the 2004-2007 period. By comparison, the national peak hit in 2010 at 19%, and is now standing at 7%, also higher than pre-recession levels.

Now for a little good news….

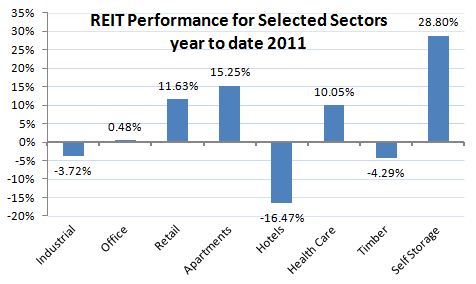

Globe Street has a great piece about the self storage market, which is doing very nicely lately. Top firms in the fiele had revenue growth of 4% to 5.8% in the 3rd quarter, with net operating income growing 7.3% to 8.6%. ranged as high as 91.7% at Public Storage. The article properly notes that this sector is now joining apartments in strong, positive territory. Overall REIT share performance, as noted in the chart below, certainly underscores this (YTD as of October 2011, data courtesy NAREIT).

While the article correctly notes the strength in this market segment, it doesn’t connect the dots vis-a-vis why. Some of this is obvious, but it bears noting due to the very signficant long-range implications. The more-or-less simultaneous strength of the apartment sector and the self storage sector isn’t coincidental — the popularity of apartments for households which WOULD HAVE been in the owner-occupied housing market is driving the need for self storage. Anecdotal evidence of late suggests that the trend is toward smaller apartments — studios, efficiencies, and one-bedrooms seem to be in higher demand lately, although I haven’t seen this formally quantified as of yet. Given that, not only is there a need for self-storage, there will also be an increased need for SMALLER self-storage units as opposed to larger ones, urban infill units (or at least units near apartment communities) and even self-storage as an adjunct to apartment communities themselves.

Long term? This market risks getting over-build whenever the housing market stabilizes. However, that seems to be several years out. In the intermediate term, one would suspect a strong demand for more units paralleling the demand for apartments.

weekend update…

Do I need to pay royalties to SNL for using that title?

Anyway, I’m headed for D.C. (among other places) this week, speaking at the meetings of the Collateral Risk Network (Hamilton Crowne Plaza, 14th @ K Street) on Wednesday. CRN is principally made up of bank lending regulators, appraisal reviewers, and others in the real estate collateral business. The primary focus of this meeting is on new appraisal regulations coming out of the recent housing finance melt-down. As a secondary issue, I’ve been asked to speak on the Gulf Oil Spill and its impact on lending, property values, and appraisals in that region.

and…. yet more on the Gulf Oil Spill

I gave a 30-minute talk yesterday in a conference-call setting to over 100 bankers and other folks in the lending industry (public policy types, regulators, etc.) sponsored by the Collateral Risk Network (CRN), a group which focuses on real estate in the bank lending setting. Thanks to our good friend, Joan Trice, the head of CRN, for getting us involved in this.

One of the CRN affiliates, FNC, is in the appraisal management business. Needless to say, the impact of the Gulf Oil Spill has an immediate and significant impact on they way they do business in the affected areas. They have established a web site with information about the crisis. Click here to access their site and blog directly,.

More on BP Oil Spill

Just confirmed — I’ll be one of the speakers at the upcoming BP Oil Spill Conference in Atlanta (June 24/25). The conference is put together by HB Litigation Conferences, the successor group to Lexis/Nexis Mealey’s Conferences. I’ve spoken at their conferences before, and they do a great job (and without sounding too self-serving, they put together a great set of speakers). Other speakers will include both the plaintiff and defense bar in this case, and I’m scheduled to go on right before the luncheon key-note address by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

For more information about the conference, please visit HB Litigation Conference’s web site.