Archive for the ‘Inflation’ Category

The Livingston Survey — Semi-Good News

Regular readers of this blog will note that I’m enamored with the Philadelphia FED’s surveys of professional economists. They actually do two surveys — one quarterly series, which has a slightly larger survey base, but doesn’t go into as much depth; and the semi-annual Livingston Survey, which has a smaller audience but a lot of detail. For direct access to the current Livingston Survey, click here.

Bottom line? The first half of 2011 isn’t as rosy as economists previously predicted, but they’re still modestly bullish on the second half of the year. Currently, the annualized GDP estimate is an anemic 2.2%, down from an almost-equally boring 2.5% in the December survey. However, GDP growth in the second half of the year is expected to be even stronger than previously thought, with second-half growth forecasted at an annual rate of 3.2%. More significantly, previous estimates of unemployment are being cut. In the last survey, economists collectively projected that year-end 2011 unemployment would stand at 9.2%; today, that projection has been lowered to 8.6%. Of course, these projections were surveyed before the most recent nasty jobs-growth reports, so everyone who uses this data is taking a bit of a “wait and see” prospective.

The nasty news is on the inflation front — prior estimates put the consumer price index rise from 2010 to 2011 at 1.6%; current consensus thinking is 3.1%. While that doesn’t sound like much, the producer price index is even worse — a prior estimate of 1.9% is now being revised to 6.3%. Both indices are expected to settle down in 2012, but we can only hope.

With that in mind, projections of T-Bill and T-Note rates are, not unexpectedly, higher than previously thought. The current 3-month T-Bill rate (as of this morning) is 0.04%. Current thinking is that we will end June in the range of 0.08%, but that by the end of 2012, 3-month bill rates will be up to 1.58%. Ten-year Note rates will follow a similar, but slightly flatter pattern (representing a slight expected flattening in the yield curve). The 10-year composit Note rate as of this morning (according to the Treasury Department) was 3.77%. Economists actually project it will decline a bit by month-end (to 3.25%), then rise slightly by the end of 2012 to 4.5%.

Phily Fed — Econ Forecast

One of my favorite economic touchstones is the quarterly survey of professional economists by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank. Forty-four economists are surveyed, including such notables as Mark Zandi from Moodys, John Silvia from Wells Fargo, and Neal Soss from Credit Suisse. The focus is on “practicing” economists rather than “academics”, and as such gives a great snapshot of what decision makers at major corporations are thinking.

The Phily Fed then takes a synopsis — both a mean and a distribution — of their collective thinking in several key areas, such as Real GDP growth, unemployment, monthly payroll growth, and inflation. The interesting factors include both the current thinking, the CHANGE in current thinking (from the previous projections) and the probability distribution.

Current thinking about GDP growth is a bit less optimistic than it was before. As noted in the graph below (reproduced from the Phily Fed’s report), prior consensus thinking put GDP growth in the 3.0% to 3.9% range, while the current consensus mid-point is between 2.0% and 2.9%. Good news — hardly anyone projects negative GDP growth for this year. As we get into out-years (the graphics are on the Phily Fed’s report), which you can download by clicking here ), the consensus is a bit blurry, but in general most economists still see GDP growth postiive and between 2% and 4%. Unfortuantely, this isn’t the best of news — for the U.S. economy to really get back on track, much stronger GDP growth is needed (solidly high 3% range and even above 4%).

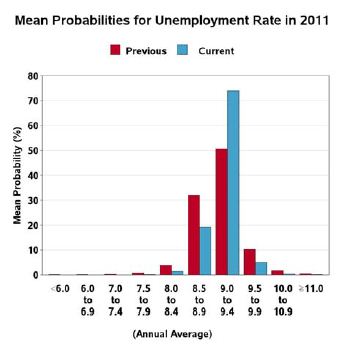

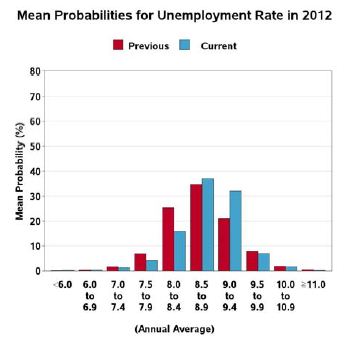

Unemployment projections for 2011 are somewhat rosier. In the prior survey, the mean projection was in the range of 9.0% to 9.4%, with a significant number of economists projecting from 9.5% to 9.9%. Currently, the mean is 8.5% to 8.9%, and a signficant number project in the 8.0% to 8.4% range — a very real shift in the outlook for the nation’s economy as we head into the second half of the year. On the downside — projections for out-years (2012, 2013, and 2014) show a very slow restoration of “normality”, with mean unemployment projections above 7% in all years.

One piece of good news — and this may be the FED patting itself on the back a bit — is that its inflation projections have been quite accurate over the years, and they continue to forecast exceptionally low CPI changes over the next ten years. While the median forecast is up slightly from last quarter (2.4% up from 2.3%), this continues to be great news for consumers and bond-holders. Notably, as you can see from the graphic, there is a fair degree of agreement among economists surveyed — the interquartile range is less than a percentage-point.

Two quickies from the WSJ

Page C1 today has two important articles that caught our eyes. I’ll write about the first right now, and follow up with the other one later today. First, Kelly Evans contributes “Overlooked Inflation Cue: Follow the Money.” It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone that money supply growth in the western economies was rampant during the run-up to the current recession. In the U.S. and the U.K., M-2 growth peaked in late ’07 to early ’08 (you don’t have to be a monetarist to figure that out). The Eurozone kept pumping money at faster rates right up to mid ’09

Where money supply growth went from there, though, was a bit of a mixed bag. In the U.S., the annual growth in M-2 fell from a peak of about 12% right before the recession to a low of about 1.5% in early ’10, and has stayed below 3% since. (This basically supports my contention that the sturm-and-drang over QE-2 was all politics.) The U.K.’s growth rate peaked at about 9%, fell earlier than ours, and hit its bottom (about 2%) in mid ’09. Intriguingly, the U.K. money supply growth rate bounced back immediately, with the virtual money presses running full-speed to get the money supply growth rate back up to about 6% in early ’10, but then falling off to about 4% today.

In the Eurozone, the money supply growth tracked very closely with the U.S., bottoming with ours in mid ’10, but since then, the European bankers have started pumping money back into the system, with their M-2 growth rate headed continuously back upwards (at about 4% today).

There are two important implications for all of this (plus my afore-mentioned observation about QE-2). First, the three big western currencies are on decidedly different tacks. The idea of opposing viewpoints among the big western central bankers is not well explored in today’s decidedly multi-polar world economy. (Back when western banking was a closed system, everyone else in the world could only sit back and watch. Now that the Chinese — and even the Japanese with all their other troubles — are more than sidelines spectators, one can only wonder how disagreements among the western bankers will play out.)

Second, though, the really significant point is that despite all of the different paths of M-2 since 2009, all of the growth rates are decidedly down from the earlier peaks. From a real estate perspective, this has major implications. As investors diversify away from stocks, real estate and bonds have a certain equivalency. In a no- or low-inflation scenario, bonds are viewed as the more secure investment. In a higher-inflation world, real estate is viewed as a bond with a built-in inflation hedge. Hence, lower inflation portends well for bonds but poorly for real estate.

One might argue that healthy bonds means low interest rates for real estate, but this ignores the fact that interest rates are already at historic lows. Hence, what real estate needs today is a nice raison d’être, which a tiny bit of inflation would give it. I’m NOT pro-hyper-inflation, mind you, and inflation flat-lines are overall healthy for the economy. However, if real estate investors are hoping for an inflation kick, it doesn’t look like they’re going to get it.

A last minute edit — Later in the day, I noticed that yesterday’s USA Today had a “snapshot” (a little graphic in the lower left corner of the front page) titled “Which Investment Will Perform the Best”, taken from a survey recently conducted by Edward Jones. Topping the list was Technology (33%), follwed by Gold (31%), Blue-chip stocks (10%), Real Estate (9%) and International stocks (9%). Given that gold and real estate are both thought to be inflation hedges, it appears that the market still worries in that direction.

Conerly Consulting

Dr. Bill Conerly of Portland, Oregon, produces a wonderful little economic report called the Businenomics Newsletter. You can check it out here. While it is heavily Pacific Northwest focused, he has some great insights into the “big picture” of the U.S. economy as a whole. I highly recommend his research, and (as long as I’m in the promotion game), he’s a great public speaker.

He discusses two key elements of the “end of the recession” right up front — the current consensus forecasts of strong GDP growth for the next two years and the current “bounce-back” in consumer spending (which fell off significantly from mid-08 to mid-09). Unfortunately, capital goods orders are only sluggishly recovering, and state-and-local budget gaps continue to be a drag on the economy.

As for construction, the decline is over, but the bounce-back is sluggish. Residential construction fell from an annual rate of about $550 Billion in the 2007 range to about $250B in 2009, and continues to flat-line there. Private non-residential peaked at about $400B in 2008/09, and has since declined to about $250B (where it’s been hovering for since early 2010). Public non-residential has been on a bit of an up-swing all through the recession, but is still barely above 2007 levels (about $300B). In short, these three sectors taken together have more-or-less flat-lined for the past year and a half or so, and appear to be staying there for the time being.

Anyone who reads the paper or watches the news on TV knows we’re in the midst of a raw materials crisis, with aggregate materials prices (the “crude materials index) up about 25% from its recent mid-2009 low. However, the price index is still well-below early 2008. Conerly suggests that the rise is “hard on some, but will not trigger general inflation.”

The money supply (M-2) continues to grow, and QE2 has apparently not had an inflationary impact, at least from reading the charts. Indeed, prior to QE2, the money supply chart looked like it was ready to flat-line. In total, as Conerly notes, the stock market appears to be happy that the economy is growing again.

Paul Krugman’s Column

Frequently I disagree with Prof. Krugman, but I nonetheless enjoy reading what he has to say. His writing is clear and lucid, and he backs up what he has to say with facts rather than simplistic conjecture. Nobel Prize Winners tend to write like that.

Today’s column in the New York Times is no exception, and this happens to be one of those times that I agree with him. Indeed, I think he doesn’t go far enough. I’ll leave the bulk of what he’s said for you to read on your own, but basically he ties global warming (even if you disagree with the theory, you can’t argue with the empirical observations) to floods, famine, and food inflation. Many critics (the Chinese, right-wing-ers, etc.) blame Ben Bernake and QE2 for the crisis. That theory has a real cart-before-the-horse problem. As it happens, global food price inflation became a reality before QE2, not after. Some theorists would also blame China and other developing nations — as their economies grow, their people want and indeed need better calorie counts. City dwellers have less time to prepare complex meals from simple ingredients, thus adding to the food logistics chain.

Krugman draws, I think, a difficult but correct conclusion that global unrest (Egypt, Tunisia) has to be placed in the context of food prices. In developing countries, food makes up a much larger portion of consumption expenditures than it does in the U.S., Japan, or Europe.

Where Krugman stops short, unfortunately, is the more direct implications for the U.S. Authoritarian governments who draw this lesson properly will find themselves caught between a rock and a hard place. On one hand, they will want to pay workers more, either directly (through higher wages) or indirectly (through food subsidies). China, with enormous cash reserves, has the easiest time of this. Indonesia, for example, will face problems. On the other hand, rising wages means either directly raising the costs to the consumers (that’s us and our European friends) or indirectly raising it via currency manipulation (which few countries have the ability to do). Of course, consumers faced with rising prices have the option of decreasing consumption, something which is fairly easy to do when we’re talking about non-essentials. Declining consumption leads to unemployment abroad, which frightens the daylights out of authoritarian regimes.

U.S. consumers have enjoyed rapid increases in consumption with relatively flat-lined prices for the last three decades, due to the juxtaposition of relatively flat commodity prices (food, energy, raw materials), rapid increases in productivity, and global application of the law of comparative advantage. Spikes in commodity prices could change all of this, as we saw in the 1970’s, and THAT may be the most important thing to look at in the economy right now.