Archive for the ‘Finance’ Category

GDP, Housing, and post-Thanksgiving musings

First, the good news. My good friend, Dr. Bill Conerly, in his Businomics blog of 11/17, brought to my attention Dr. Mark Perry’s Carpe Diem post of that same date. Dr. Perry brings up two great points, both good news for the U.S. First, the global GDP is poised to hit $50 Trillion for the first time this year, up 2.7% from last year. Second, and a bit unfortunately, this good news isn’t evenly distributed. Somewhat surprisingly, the U.S. share of Real GDP has held fairly constant for the past four decades, hovering between 25% and 30% of the world’s total. While the U.S. share is down slightly from its peak a decade ago, it’s actually higher today than it was in the early 1980’s.

The most interesting — and obvious — observation is that growth in the Asian share has come at the expense of the Europeans. For more, I’d refer you to Dr. Perry’s exellent commentary on this.

In addition, this week’s Economist magazine just hit my mailbox. I cannot speak to highly of this weekly — anyone who really wants to be informed on the complexity of the world needs to read it cover-to-cover the moment it’s printed. It comes with a decidedly British feel and a slightly right-of-center focus, but with those caveats aside, it’s simply the best news magazine in the world. And no, I have to pay for my subscription just like everyone else.

This week’s issue has an intriguing piece on the softness of global housing market. I’ve long held that corrections in the U.S. bubble were triggered by the inablity of the secondary financing market to accomodate slight changes in underlying default rates. In short, the secondary market is basically made up of derivatives of derivatives of derivatives. Each layer of “securities” (a more ironic name for these instruments could not be found) assumes away a certain level of risk, applying a totally falatious reading of Markowitz. However, the pain in the U.S. market may be close to ending, as the bubble in home ownership rates nears a nadir.

The more global problem, however, is that other markets have not fallen in the same way as the American market. In the U.S., house-price-to-income ratio now stands below 80 (1977 to 2011 average = 100). On the other hand, Britain and France — two economies with some pent-up troubles ahead of them — both stand at between 120 and 140, and indeed France is near its peak for the past three decades. (Britain is slightly down, but not by much). By their measure, most of Europe (except Germany and Switzerland) is in trouble, as well as Canada and Australia. Japan has now declined even more than the U.S., but Japan’s market was widely considered to be terrifically overvalued before (maybe even worse than America’s).

While this is new territory for most countries, Britain’s housing market got out-of-whack back in the late 1980s, and fell about as far, relatively, as the U.S. market has fallen in the past few years (and over about the same time frame). If Britain’s experience provides any indication for the U.S., it’s market stayed relatively low for several years before rebounding.

Not all economists agree with this perspective, and many feel that systemic low interest rates make this particular measure of housing prices invalid. The problem with this perspective is that European interest rates are rising, and may continue to do so in the wake of the various debt problems in the Eurozone.

Predicting recessions

The onset of a recession is much like the onset of a bad cold, or perhaps the flu. You THINK you know you have it, and then the next morning you wake up feeling like you’ve been hit by a truck.

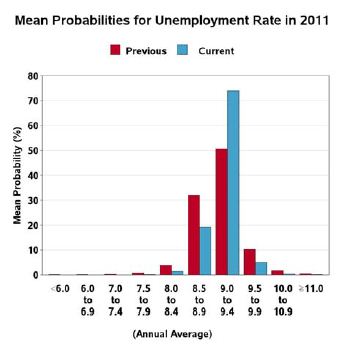

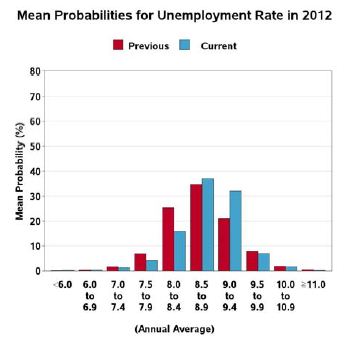

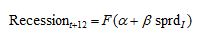

What if we had a tool that could actually PREDICT a recession a year or so in the future? Wouldn’t that be handy? In fact, two researchers at the New York Federal Reserve Bank actually developed something a few years ago (early 2006, to be precise) that seems to have some promise. They noted that the spread between 10-year Treasuries and 3-month Treasuries was a leading indicators of economic activity (which makes intuitive sense). Using historical data, they craft a formula which calculates the probability of a recession occurring in the coming 12 months:

…where “spread” is the difference, in percentage points, between the 10-year yield and the 3-month yield and F is the standard normal distribution (mean of 0, standard deviation of 1). Plotting their data over time, and comparing to the onset of a recession, they get Chart 2. While no model is 100% predictive, this one clearly indicates that a recession is highly probable whenever the spread-indicated probability gets much above 30%.

…where “spread” is the difference, in percentage points, between the 10-year yield and the 3-month yield and F is the standard normal distribution (mean of 0, standard deviation of 1). Plotting their data over time, and comparing to the onset of a recession, they get Chart 2. While no model is 100% predictive, this one clearly indicates that a recession is highly probable whenever the spread-indicated probability gets much above 30%.

Of course, the statistical math can get a bit hairy, but there is a handy rule-of-thumb. As you can see from Chart 1, whenever the spread turns negative, a recession is fairly likely in the coming months. Why? Because a negative spread suggests two things: first, that borrowers have little demand for long-term money, and second that investors are looking for a safe place to tuck money away that they don’t think they’ll need for a while, and aren’t afraid of inflation. In short, the yield spread constitutes a fairly accurate survey of investor expectations about the economy.

Unfortunately, Estrella and Trubin end their research with July, 2006, which at the time was giving off a 27% recession signal for July, 2007. A great test of their model would be to see if it would have predicted the onset of the December, 2007, through March, 2009, recession. We used the same H.15 data from the Federal Reserve Board, and came up with the following:

Unfortunately, Estrella and Trubin end their research with July, 2006, which at the time was giving off a 27% recession signal for July, 2007. A great test of their model would be to see if it would have predicted the onset of the December, 2007, through March, 2009, recession. We used the same H.15 data from the Federal Reserve Board, and came up with the following:

Ironically, our analysis shows that the probability of a recession crossed the 30% barrier on July 31, 2006 — a month after the cut-off of their study, and 16 months before the official “onset” of the recession.

By the way, if you’re worried, the current probability is at 1.8%. We’ll keep you posted.

Mueller’s Market Cycle Monitor

Dr. Glenn Muller of Dividend Capital Research has one of the more intuitive “takes” on the commercial real estate market. His Market Cycle Monitor is based on a piece he wrote for the journal Real Estate Finance back in 1995. It notes that a given type of real estate (office, industrial, etc.) in a particular geographic market (New York, Seattle, etc.) moves through a cycle which can be broken down into four phases: expansion, hypersupply, recession, and recovery. The driving force through these cycles is property occupancy — when occupancy levels rise, developers are encouraged to build new product, which leads into a hypersupply situation where occupancies fall and properties go into recession. For a more detailed look at his model, click on the link above, which will take you to the Dividend Capital website where you can view the 3rd Quarter report.

In short, he finds that as of the 3rd quarter, 2011, most property types in most markets are in the early stages of recovery. The office market nationally, as well as in about a third of the cities he follows, is still in the late stages of recession (except Sacramento, which is in the early recession stage). Austin and Salt Lake seem poised to break out into expansion.

In the industrial market, every region is in recovery, with Pittsburgh, Riverside, and San Jose the furthest along. However, none of these markets evidence being close to expansion at this time. As for apartments, every market is in some stage of recovery, with Austin close to breaking out into expansion. Lagging the recovery are New Orleans, Norfolk, and Richmond. Nationally, the apartment market is right in the middle of recovery, with expansion still a few steps in the future. The retail market is in about the same position as apartments, but with Long Island, San Diego, and San Francisco furthest along. Nationally, we’re still close to the beginning of a retail recovery and not very far along. Hotels seem to be slightly further along than regail, with Honolulu, New York, and San Francisco leading the pack (and poised to break out into expansion).

Bottom, bottom, who can find the bottom?

In the owner-occupied housing sector, a “bottom” seems to be like the weather — everyone talks about it, but no one seems to be able to do anything. I’ve been positing that a “bottom” (or at least “stabilization”) won’t be a reality until we get some sort of stability in the home ownershps rate, which has been creeping downward for about 5 years. If that stabilizes (and my own projection is somewhere between where it is — about 66% — and 64%), then prices will have the necessary demand stabilization to perk up.

Money Magazine, on the other hand, says “lo, the bottom is nigh”. Specifically, they say that in the coming year, 95% of home-ownership markets that they track will begin to rise. Caveats about, of course — “The median expectation among more than 100 economists and real estate pros surveyed by MacroMarkets is that home values will inch ahead by a mere 0.25%, compared to their 2011 median forecast decline of 2.8%. They also foresee annualized gains through 2015 of just 1.1%, as the real estate market slowly works its way through a mountain of foreclosures.”

Why the continued sluggishness? The folks at CoreLogic tell us that the “shadow market” is 5.4 million homes, including bank-owned properties, homes in the foreclosure pipeline that haven’t hit the market yet, or properties where owners are seriously behind on payments. Now, compare that forecasts from FreddieMac that the entire market for homes in this coming year will be 4.8 million, and that a 6-month inventory of available properties is generally thought to be healthy, and you can see the supply-demand imbalance.

Mark Fleming, chief economist over at CoreLogic, uses the analogy of a flood. “The water is very deep in the living room, but it’s no longer getting deeper and is starting to recede.”

Hard to feel sorry for Bank of America…

….but let’s try, just this once. As pretty much everyone knows, over the past few years, they’ve repeatedly shot themselves in the foot, then reloaded, then opened fire again. Public displays of embarassment like the $5 debit card fee are just the tip of the iceberg (and, indeed, helped them shed a lot of low-return or even negative-return depositors who could and should be better handled by credit unions).

More interesting has been their acquisition of Countrywide a few years ago, which everyone agrees was a debacle, and their subsequent messy handling of CW’s meltdown. However, now that they’re in such a fiscal and regulatory mess, BofA is having to shed itself of assets — at firesale prices — that in good years they’d want to keep. The latest example is BofA’s interest in Archstone Residential, one of the biggest apartment owners in the U.S. with 78,000 units. Recall that apartments are doing VERY well today, and are the one sector of the real estate industry which weathered the recession storm nicely. Indeed, given the trend in apartment valuation, BofA would be well advised to hang onto this asset for dear life.

BofA and Barclays acquired a 53% interest in Archstone Residential via a Lehman Brothers-led acquisition. The original purchase price in 2007 was $22 Billion. That works out to about $282,000 per apartment, which is pretty darned high, admittedly. Let’s suggest that a reasonable value would be in the range of $200,000 per apartment, or about $15 Billion. Of course, REITs often sell for a premium over net asset value, so the $22 Billion acquisition price probably wasn’t terribly off the mark at the time. Thus, the total net asset value $15 to $16 Billion, which indeed is close to Dow Jones’ current estimate of $18 Billion.

However, who has $15 to $16 Billion laying around? (Or, to be specific, 53% of $15 to $16 Billion, or about $8 Billion?) Up to the plate steps Sam Zell — yes the same guy who gave us Equity Office Properties. He now owns Equity Residential, which is making a bid for the 53% at….. (drum roll, please)….. $2.5 Billion in cash and stock. In general, this works out to about $64,000 per apartment, which is painfully low. Note also, that Zell is the winning bidder, having out-bid AvalonBay, Blackstone, and Brookfield.

Why is BofA letting this go so cheap? For one thing, they don’t have much choice. The regulators are making them dump whatver they can at Craigslist prices to generate cash and cash-equivilents. For another, the nasty market we’re in makes cash king — no one is financing this sort of deal, not even at these firesale prices.

In some ways, Sam Zell is a lot like Warren Buffett. Often it’s said — mistakenly — that you could do worse than simply buying stock in whatever Buffett buys. That’s true, but only if you pay the prices (usually deeply discounted) that Buffett pays. Now, the same appears to be true with Zell.

Philadelphia FED Business Conditions Index

While its focused on their region, the Philadelphia FED’s announcement this morning wasn’t good news, despite the spin they put on it. In short, the index declined significantly from October to November, albeit remaining in positive territory. To quote:

Responses to the Business Outlook Survey this month suggest that regional manufacturing is expanding, but at a slow pace. The survey’s broad indicators for activity, shipments, and new orders recorded positive readings this month, but all declined slightly from their October readings. Employment conditions improved, as indicated by increases in the indexes for employment and average workweek. The broadest indicator of future activity showed marked improvement, and firms were notably more optimistic about future employment.

In addition, inventories went up in the most recent survey, which is generally not very good news.

On the bright side, their survey of current and future activity is now at its highest level in quite some time, and future activity is also forecasted to continue strong. Hopefully, the October-to-November decline is simply a seasonal abberation, and not a long-term trend.

Greenfield’s Manufacturing Research Partnership

A really big “shout out” to Dr. Cliff Lipscomb and all of our economic research team, who have inked a partnership with the U.S. Department of Commerce, the National Institute for Science and Technology (NIST) and Georgia Tech to investigate NIST programs in manufacturing. Following is the text of the press release, which is also featured on a number of web sites, including RICS-Americas (http://tinyurl.com/7h2summ):

Greenfield Advisors and Georgia Institute of Technology to Evaluate the NIST MEP

November 15, 2011

ATLANTA, GA –The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), a program of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), is a nationwide network of manufacturing extension centers that provide services to small and mid-sized manufacturers to increase their competitiveness and productivity. Since 1989, the MEP has worked with manufacturers to provide cost-effective expertise and assistance to improve their manufacturing processes, to provide workforce training, and to implement new technologies. The MEP also focuses on supply chains, providing growth and innovation services to firms. Approximately 7500 client firms are served annually.

Many stakeholders view the primary mission of the MEP as materially improving the long-term viability of US manufacturing. To meet this mission, MEP must demonstrate persistent, long-term improvement in client performance. In addition, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has asked federal programs to make decisions regarding assessments of program performance based on evidence. Recently, the U.S. Department of Commerce awarded Greenfield Advisors and the Georgia Institute of Technology $249,000 to evaluate the effects of the MEP program. In this work, we will be evaluating the economic performance and survival of U.S. manufacturing firms, comparing the outcomes of MEP clients to nonclients, controlling for other factors. Our focus will be on establishments that received MEP services between 1997 and 2007. We will estimate the effect of different levels and types of MEP services on output and productivity growth over this period. The novelty of our approach is the econometric methods we will use to find the determinants of economic performance and survival of MEP clients while adequately controlling for selection bias.

Greenfield Advisors’ partner in this research is the Georgia Institute of Technology. Dr. Jan Youtie, Manager of Policy Services and Principal Research Associate at Georgia Tech’s Enterprise Innovation Institute, commented “the MEP is an important program targeted specifically for manufacturing. We are excited to work with Greenfield Advisors on this important evaluation of the effect of program services on manufacturing performance and survival.”

The MEP evaluation will take approximately 1 year to complete. Greenfield has assembled a blue-ribbon Technical Advisory Group (TAG) to consult on the development of the research and provide guidance as necessary. Members of the TAG include former and current chief economists within the U.S. Department of Commerce as well as other well-known economists at the U.S. Census Bureau and the University of Texas at Austin. You can learn more about the MEP at http://www.nist/gov/mep.

Google’s real estate index

Yeah, me neither….

I was doing a search for some real estate stats today, and happened upon the neatest little toy — it’s Google’s index of real estate searches, which you can access via: GOOGLEINDEX_US:RLEST. According to the gurus at Google, it tracks queries to “real estate, mortgages, rent, apartments, and so forth.” Also, according to them, you can use it to compare to real estate investment indices.

Having SOOOOOOO much spare time on my hands (my colleagues here at Greenfield are shuddering at that), I decided to give it a test. I downloaded the index’s raw data for the last 7 years (believe it or not, you can do that), and then downloaded the iShares Dow Jones Real Estate pricing data for the same dates. A little manipulation was in order, because Google gives data for 7 days a week, but of course the stock market is only open 5, and then not on holidays and such. The difference (about a 1000 days) I made up by simply taking the closing prices on Friday and spanning that over the weekend. You get the picture.

The graphic looks like this:

Not being one to settle on graphics, I then ran a correlation examination on the two indices. Guess what? Yeah, nothing. To be specific, I get a correlation coefficient of 29.6%, which is fairly close to meaningless. This dog don’t hunt, as they say.

Oh well, sometimes it’s fun to find out what DOESN’T work. In short, the volume of Google searches on real estate may have some interesting insights buried deep within it, but I don’t see it yet.

Now for a little good news….

Globe Street has a great piece about the self storage market, which is doing very nicely lately. Top firms in the fiele had revenue growth of 4% to 5.8% in the 3rd quarter, with net operating income growing 7.3% to 8.6%. ranged as high as 91.7% at Public Storage. The article properly notes that this sector is now joining apartments in strong, positive territory. Overall REIT share performance, as noted in the chart below, certainly underscores this (YTD as of October 2011, data courtesy NAREIT).

While the article correctly notes the strength in this market segment, it doesn’t connect the dots vis-a-vis why. Some of this is obvious, but it bears noting due to the very signficant long-range implications. The more-or-less simultaneous strength of the apartment sector and the self storage sector isn’t coincidental — the popularity of apartments for households which WOULD HAVE been in the owner-occupied housing market is driving the need for self storage. Anecdotal evidence of late suggests that the trend is toward smaller apartments — studios, efficiencies, and one-bedrooms seem to be in higher demand lately, although I haven’t seen this formally quantified as of yet. Given that, not only is there a need for self-storage, there will also be an increased need for SMALLER self-storage units as opposed to larger ones, urban infill units (or at least units near apartment communities) and even self-storage as an adjunct to apartment communities themselves.

Long term? This market risks getting over-build whenever the housing market stabilizes. However, that seems to be several years out. In the intermediate term, one would suspect a strong demand for more units paralleling the demand for apartments.