Posts Tagged ‘Economy’

The K-Shaped Economy

“I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore!” (Howard Beale, played by the actor Peter Finch, in the movie “Network”, 1976)

In the coming days you’re going to hear the phrase ‘K-Shaped Recovery’ bantered about by economists. It’s a little misleading, because it suggests we’re in the midst of some kind of economic recovery. In fact, we’re not, but it harkens back to basically everything that’s happened since the Pandemic, and it also explains the National and World politics, the state of the nation, and the state of everyone’s pocketbooks.

In a ‘K-Shaped’ economy, there are winners and losers. Now, you might say, “Hey, John, haven’t there always been winners and losers in the economy?” and I would say, “Yeah, but generally not so predictably systematic.

If you went into the pandemic with money/assets, or a job in high-demand sectors, or both, then you’ve done quite well over the past five years. If you didn’t have money/assets, and had a job in low-demand sectors, then you’ve done quite poorly.

The 2024 election turned on this issue. Most (but not all) economic winners were likely to vote to stay the course. Economic losers were likely to vote to change. Change won. Today, though, the economic losers are getting worse off, and the economic winners (amazingly enough) are getting better off.

So, what can be done to fix this? Pretty much the opposite of what’s being done right now. First, America benefits from wide-open free trade. We send dollars (which we can print by the bucketload) in return for cheap goods. We also sell lots and lots of stuff that provides lots and lots of employment, like soybeans and airplanes and Hollywood movies and the upper echelons of technology.

Second, the social safety net is crumbling. It’s crumbling because very short sighted billionaires wanted tax cuts, which in the long-run are counterproductive to their best interests. These billionaires generally sell stuff to consumers. If consumers at the bottom half of the economic ladder cannot afford to buy their stuff, then in the long run, Amazon and Walmart and Apple have unsustainable business plans. For example, people make bad economic decisions in the absence of a good health care system, a healthy housing market, or stable food prices.

Third, controlled and regulated immigration is and always has been extraordinarily healthy for the economy. It brings in hard workers who are anxious to take the lowest jobs on the ladder, and pushes higher-paying jobs up the economic ladder.

Fourth, education is key. Instead of eviscerating our schools, we should double-down on public education and add to that skilled trade education. Teachers should be among the best paid professionals in our society. (Right now, nursing schools cannot find professors because the private sector pays so much better than the nursing schools can manage.)

Fifth, we should develop trade alliances with the other democracies in the world, rather than force them into the arms of our economic enemies. China’s belt-and-road strategy was brilliant. We can duplicate that with agencies like USAID. The free nations of the world would much rather ally with us, but we’ve shut the door on them.

Sixth, our infrastructure – and particularly our energy grid – is in serious need of attention. This is a powerful investment, and would have the same multiplier effect as the development of the interstate highways in the 1950’s and 60’s.

Are you mad as hell? Yes, you ought to be. Particularly if you’re a soybean farmer, or a recent graduate looking for a job, or a contractor who can’t afford to buy lumber, an immigrant who just wants to put in an honest day’s labor, or a young person who wants to buy a house but can’t make the down payment.

A bit about tariffs.

We know, as a matter of empirical evidence, that chaotic tariff wars are horrendous for the economy. The research on that sailed a long time ago. So why do some countries still use them?

First, it’s helpful to understand an economic truism of the Law of Comparative Advantage. We teach a simplified version of this to undergraduates (at least the ones who pay attention) and Nobel Prizes have been won in its wake. Indeed, if you ever saw the movie “A Beautiful Mind” about the life of the great John Nash, you may be interested to know that while his Nobel was about game theory, it in fact was based on his observations about world trade.

It goes a bit like this. Let’s say there are two countries (in the classic example, we use Britain and Belgium). Let’s say Britain is wealthier than Belgium (which at the time, it was) and let’s also say that these two countries both make two things — Wine and Wool, in the classical example. Now Britain, being the wealthier and more advanced nation, is better and more efficient at both products than Belgium. This would suggest that Britain should make both products and simply ignore any trade with Belgium. Britain could do that by establishing huge trade barriers — tariffs — against Belgium, much like the U.S. is doing today against, well, everyone.

However, and here’s the rub — internally, Britain is better at wine than at wool. Make no mistake, it’s better at both than Belgium, but it make wine more efficiently and more cost effectively than it does wool. Belgium, on the other hand, is better at wool than at wine. Again, it’s less efficient than Britain at both, but internally, it’s better at wool than at wine.

The Law of Comparative Advantage has proven, time and time again, that Britain would be better off making nothing but wine, and Belgium at making nothing but wool, and the two countries trading freely with one another. Tariffs, in such cases, are not only bad for the poorer country (Belgium) but also for the richer one (Britain)!

Late last year, the conservative journal The Economist proclaimed that the U.S. economy was the ‘envy of the world.’ We had amazingly low unemployment, our inflation was coming down, our GDP had been growing constantly since the pandemic, and our stock market was on a tear. Yes, we had some internal inefficiencies, but these tended to be granular and needed to be addressed with a surgeon’s scalpel, not a sledgehammer. Yes, middle class incomes had not kept up with the cost of living over the past half century, but this was a matter of income inequality and not trade imbalance, and needed to be dealt with accordingly.

Over the years, America has made LOTS of things that other countries wanted. We export vast quantities of oil and natural gas. We export significant quantities of computers, vehicles, electrical machinery and equipment, aircraft, optical and medical apparatus, and pharmaceuticals. Vast swaths of America are devoted to growing exported agricultural products, such as soy beans and corn.

Further, and this may come as a shock to some, but one of the things other countries wanted was our dollar. They hoarded it. The rest of the world used it as a default currency, the one stable currency (along with, arguably, the Euro) which could be considered strong during chaotic times. It served the purpose that gold had served a hundred years ago. And yes, we produced it by the boat load (metaphorically speaking), and foreign countries had an insatiable appetite for it.

Poor nations use tariffs in order to protect and stabilize emerging businesses. In the previous example, if Belgium wanted to build up its own domestic wine industry, it would enact a tariff on imported British wine. In the short run, and in small doses, this may work. However, in the long run, it reduces British exports to Belgium, and thus the quantity of Belgian money they have to spend on Belgian wool. (The ‘what goes around comes around’ model of the economy.) Canada has an interesting tariff on imported milk products, which was agreed to during the current president’s prior administration. Indeed, he signed off on it as part of the replacement for NAFTA. Canada admits American milk products, but only up to a certain limit, and then above that taxes American milk heavily. Make no mistake, though, this Canadian tariff is a tax on Canadian consumers. Indeed, some emerging or mid-level economic countries prefer a mix of tariffs (which are like a sales tax on their own consumers) and income taxes to finance their governments. However, tariffs, being a sales tax, are highly regressive and depress the well-being of the middle class.

Rich nations, like the U.S., prefer to use income taxes (since there is so much income to tax, and it’s more efficient and less regressive) and let the middle class prosper without burdensome tariffs. Indeed, free trade benefits rich nations, like ours, more than it benefits poor nations. Nonetheless, the Law of Comparative Advantage tells us that both rich nations and poor ones are better off without burdensome and chaotic tariffs.

But, as the country song said, “not no mo’…” It takes a long time to craft a stable relationship with our trade allies. Like dropping a valuable vase on the floor, it only takes a moment to shatter it.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D.

Some Thoughts on Housing Crisis

Last month, I had the very real pleasure of delivering a major, hour-long address at a conference in Charleston, South Carolina, on the nation’s housing crisis. In it, I discussed the overarching problem and some potential solutions, as well as some problematic ideas which are being bandied about. I’ll synopsize here today.

Right now, we have about 131.5 million households in America, a number which has been growing steadily almost without a break since WW-2. Right now, we ad about one and a quarter million households to that total each year. About two-thirds of us live in owner-occupied dwellings, a number which has remained constant for most of my lifetime.

Just focusing for a moment on the owner-occupied sector, median house prices have gone up about 317% since 1991. However, median household income has increased only about 167%. Over the past three decades, owner-occupied housing has only appeared to be affordable most of the time because (1) we had a sub-prime bubble with artificially easy money in the 1990’s, and then (2) we had very easy money – in fact, a liquidity flood — following the meltdown, and then (3) we have had extremely low interest rates until just a couple of years ago. Owner-occupied demand spiked during the recession, and as everyone knows, cheap money disappeared. Those of us with long memories recognized that today’s supposedly high interest rates were actually the norm a few decades ago. If the FED target of 2% inflation is achieved, it is still very hard to imagine mortgage interest rates coming down much below 5%.

In a reasonably efficient economy, home prices rising would stimulate homebuilders to flood the market with new product. However, a new home is the nexus of several different inputs – materials, skilled labor, land, and ‘soft costs’ (insurance, permits, mitigation fees, taxes, fees, etc.). Unfortunately, these inputs have all been problematic. Material, land, and soft costs have all risen rapidly, and skilled labor is in short supply. In many ways, builders are in worse shape than their customers.

In 2020, the Goldman Sachs housing affordability index stood at 135%, which meant that a median household had 135% of the income necessary to ‘afford’ payments on a typical 30-year conventional mortgage (with 20% down) on a median priced dwelling. Today that index stands at 70%. It is widely agreed that getting that index back up above 100% will be a herculean task.

By the way, what do we mean by ‘affordable’? In general, the total housing burden shouldn’t exceed 30% of a household’s take-home income. What do we mean by ‘housing burden’? For a homeowner, that includes payments on the mortgage (principal and interest), plus homeowner’s insurance and property taxes. Not only have mortgage interest rates soared in recent years, but also, we’ve seen insurance and property tax rates climb at above-inflation rates. While mortgage interest rates may come down in the near future, higher insurance and tax rates may be with us permanently. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that those will actually continue to significantly increase, particularly in hard-hit areas like California and Florida.

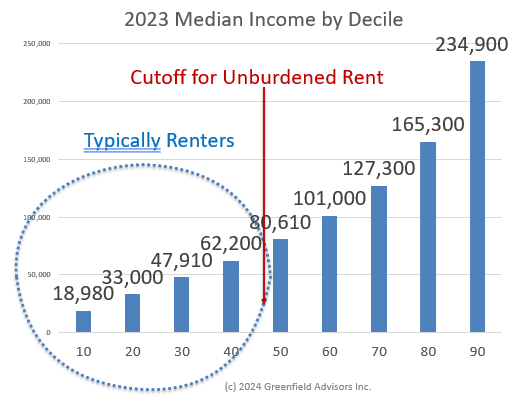

Amazingly, the rental community – about two-thirds of American households – have actually been hit worse. Note that as a general rule of thumb, renters come from the lower deciles of the income strata. Right now, the median household income in America sits at about $80,000 per year. However, the median income for the 40th percentile of Americans is only about $62,600. In other words – and this is a very rough approximation – about 40% of American households make less than about $62,200 per year. And remember, these households are more likely to be renters.

Right now, the median apartment rent in America is $1,595 per month. (The median rent on a single family detached dwelling is $2,000). Add to that about $300 per month for utilities and such, multiply by 12, divide by 30% (the threshold for ‘unburdened’ rent) and you get a household income of $75,800 per year to be considered ‘unburdened’ renting a median apartment in America. And remember, that’s a median, so fully half of the apartments in America are unaffordable for households making $75,800 per year.

Nobody in the bottom 40% of households makes that much money.

Indeed, an estimated 20 million households in America spend over 50% of their income on housing.

So how do we address these problems? We have two major sources of aid for low-income housing. First, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program provides indirect Federal support in the form of tax credits for developers of affordable housing. This program was created out of the 1986 Tax Reform Act, and until 2016 was responsible for building about 115,000 affordable units per year. However, since 2016, for a variety of reasons, the program has only helped finance about 75,000 units per year. As a result of this, in most of the country, we have fewer than 45 affordable and available units for every 100 low-income families, and in the hardest hit states, such as California, Florida, Virginia, and my home state of Washington, the number is under 30 units.

The other major source is the Section 8 voucher system. Funded by the Federal Government through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), but administered by local governments, this program provides full or partial rental vouchers for needy families earning less than 50% of local median income. However, the wait times for a voucher are awful (averaging 28 months nationwide) and only about one in four eligible households ever receive anything.

David Holt, the Republican Mayor of Oklahoma City, speaking on TV talk shows this weekend in his role with the national mayor’s association, noted widespread agreement among the country’s mayors that housing availability and affordability was their number one concern right now. So, what can we do to fix the problem.

Three ‘fixes’ come to mind immediately. First, a bipartisan group of both Senators and Congressional representatives have co-sponsored the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act (Senate bill 1557 and House Resolution 3238). This bill would fix some of the long-standing problems in the program and increase credits overall by 50%. However, the bill is currently stagnating in committee, and even though it has some powerful sponsors, it is simply not at the top of anyone’s agenda right now.

Second, some expansion of the Section 8 program is long overdue. However, the incoming administration is all in favor of massive belt-tightening. In the case of Section 8, this is woefully shortsighted, as the economic problems caused by unaffordable housing far outweigh the cost of this program. However, the attitudes on Capitol Hill are decidedly negative.

Finally, I would propose some significant overhaul in the HUD loan program (known back in my boyhood as ‘FHA Loans’). These loans provide Federal insurance – at no cost to the taxpayers – for homebuyers who meet stringent credit requirements. The loans carry extremely low down-payments – very close to zero. In the early 1980’s, when mortgage interest rates were soaring, many states were allowed to use tax exempt bonds to fund state housing finance programs which routed funds into HUD loans. This was a win-win for all concerned, and the economic stimulus of expanded housing construction far outweighed any lost revenue to the Federal coffers. However, the spread between tax-exempt and taxable bonds was somewhat greater back then, and so there was some meaningful leverage to be applied in lowering the mortgage interest rates, particularly for first-time buyers. That said, some kind of program like this, most likely using HUD leadership, would go a long way to breaking the logjam.

There are, unfortunately, some dumb ideas out there. First, a recent RAND study indicates that local governments, despite meaning well, have actually gotten in the way of affordable housing construction. The local restrictions are myriad, but as a result, the cost of building a new, affordable apartment in California, as an example, has risen to about $1 million per unit. This is utterly unsustainable.

Second, the incoming administration has posed the idea of building new homes on Federal land. Time and space will not permit me to list and discuss all of the reasons why this is a bad idea. As examples, however, it constitutes an intolerable wealth-transfer from existing homeowners to new homeowners, it runs afoul of the Federal mandate that any transfer of Federally owned land be at market value, and let’s face it, there is little available Federal land in any of the places where people actually want to live.

Finally, the incoming Administration has made it a priority to re-privatize Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These private sector groups, with the implicit guarantee of the full faith and credit of the US Treasury, are the primary secondary market makers for mortgage loans. During the housing meltdown, they were in effect ‘taken over’ by the U.S. Treasury, under the auspices of the Federal Housing Finance Authority, and now all of their considerable profits flow into the U.S. coffers. Both political parties have agreed that reprivatization is a goal, albeit for different reasons. However, the devil is in the details here, and a slap-dash reprivatization of organizations with combined balance sheets exceeding $4 TRILLION, would, in some estimation, add considerable burden to the current mortgage interest rates.

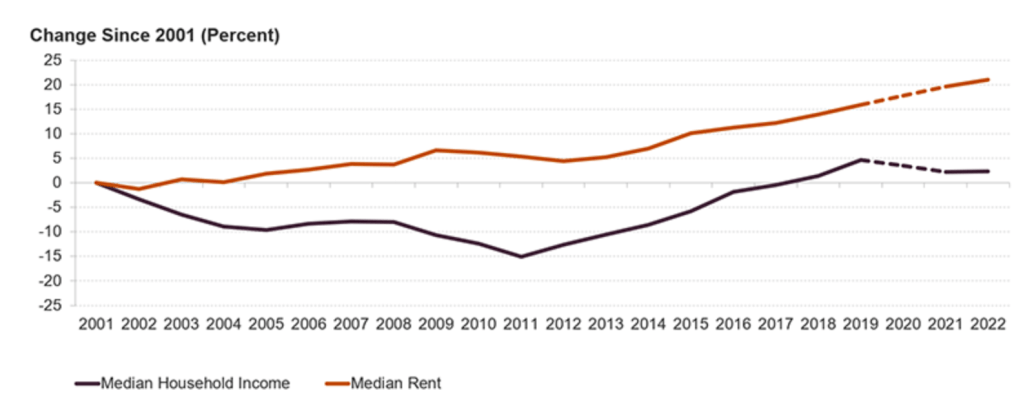

In the end, though, the real crisis is less about housing and more about affordability. In the owner-occupied sector, for example, house prices have been going up, on average about 2% above inflation year-after-year since WW-2. That’s really not a bad thing. It means that home ownership is a really good investment and a nearly perfect hedge against inflation. Even during the housing crisis following 2006-ish, while house prices dipped, they soon reverted to the mean, and today house prices are about where they would have been had the housing crisis never occurred. Over the same post-world war period, household incomes generally also trended upward, more or less, until the 1970’s. However, since then household income has simply failed to keep up with the cost of housing. In short, this current crisis has less to do with the cost of housing and more to do with the stagnating fortunes of middle-class Americans.

As always, if you have any comments or questions on this or any other real estate related topic, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

Where will YOU sleep tonight?

Over the past few years, I’ve focused this blog on Real Estate Investment Trusts. While I’m NOT backing away from investments in that arena (I still own ACCRE, which is a small REIT fund-of-funds), I am presently focusing more of my attention on housing. Where most of us sleep at night comes in several different varieties – single family detached homes, owner-occupied condominiums and other attached housing, rental homes and condos, and of course rental apartments.

According to the most recent statistics I have, there were about 145.3 million ‘housing units’ in America as of July 1, 2023, or about 1 for every 2.3 people. Of the occupied units, about 65.8% are ‘owner occupied’ (both single-family and attached), while the remainder are some sort of rental units, such as single family rental houses or apartments. Over the past couple of years, we’ve seen an increase in housing units of about 1% per year, more or less. That’s about two to three times the rate of growth in the population, so… sounds like everything’s OK, right?

Yet, there is enormous angst about housing availability and affordability in all corners. At the low end of the economic spectrum, about 1.25 million people experienced homelessness a some point in 2020, the last year for which HUD has published data (according to the US Government’s Interagency Council on Homelessness). As we move up the economic ladder, the working poor, when they can find housing, are forced to pay increasingly large portions of their budget for shelter, thus crowding out food, health care, and other necessities of life. Even the so-called ‘middle class’, if you can still call it that, find homeownership prohibitive.

Most pundits (and I’m citing CNBC here) tell us that as a general rule, the total cost of housing (rent or mortgage payment plus utilities) should be no more than 30% of the household’s budget. Ironically, renters, who are often the ones who cannot afford home ownership, seem to have it worse. As of the 2021 American Housing Survey, over 50% of renters report paying over that 30% threshold. When broken down by income level, about 64% of households earning less than $50,000 per year report paying over the 30% benchmark. According to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, rent has increased over 20% since 2001 even after accounting for inflation, while median household income is virtually unchanged.

For those trying to join the ranks of homeownership, the story is even worse. Taking the longer view, in 1985, the median household income in America was $22,400, and the median home price was $78,200, for a ratio of 3.5. Even back then, steep interest rates consumed nearly half of a typical household income in mortgage payments. Today, in America, with lower interest rates fueling a housing demand, the median sales price of a dwelling is $433,100, and the median household income is $74,600, resulting in a ratio of 5.8.

Wells Fargo and the National Association of Homebuilders conduct an annual survey of homebuilder sentiment, which is a weighted average of current housing starts, anticipated starts over the next 6 months, and ‘buyer traffic’, which is essentially a measure of buyer interest in new homes. As of October, 2024, the index stood at 43, which for the sake of comparison, is about where it stood in the middle of the 2008-10 housing crash. Not surprisingly, housing starts right now are only 992,000 per year, about where it stood 40 years ago.

Many buyers and apartment developers blame interest rates, but that’s only part of the story. Costs have skyrocketed all across the nation, not just ‘hard costs’ (sticks, bricks, and labor) but also ‘soft costs’ such as regulatory burdens, permitting fees, and marketing costs. In the ‘hottest’ areas – the places where people want to live – the cost of land has also become burdensome. Forty years ago, merchant builders considered land should cost between 30% and 40% of the selling price of a single family dwelling. Today, in the top markets, that number can exceed 50% or more.

Over the course of the next few weeks and months, I’m going to explore some of these issues in more detail. As always, if you have any specific questions or comments, please let me know.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI

4/27/09 — The Death of Efficiency?

I was trying to explain to a lawyer why AIG was “too big to fail”.

While I let that sink in, I’ll tell you a little story. Back when I was an academic, every summer our Finance department would have a little private, in-house, self-edification symposium we jokingly called “Finance Camp”. Usually running 4 to 6 weeks, it would consist mainly of a weekly, afternoon session of 1 – 2 hours, in which each of us would take turns making a presentation on some aspect of that summer’s theme. One summer it was bond portfolio duration. Etc. You get the picture?

Anyway, one summer, we decided that the theme would be “bankruptcy”. While planning for the sessions, we realized that the Law School also taught “bankruptcy”, so we should invite the 3 or 4 law professors who taught that subject. We planned for a big “round robin” intro meeting, followed by alternating weeks of presentations from finance and law. Good idea, right?

Sigh… as it happened, not only were we talking about two different SUBJECTS, we were frankly talking about two different LANGUAGES. Case in point — from a finance perspective, if bankruptcy is properly priced ex ante, then the event of bankruptcy is irrelevant. From a legal perspective, the very concept of such irrelevance is inconceivable.

So, back to AIG. Everyone, I guess, seems to bemoan the fact that we have (or had) companies in America that were “too big to fail”. Because what they do is so clouded in mystery, it’s hard for the person on the street to grasp how badly the economic machinery would suffer if AIG failed. Imagine, instead, if Boeing and Airbus were one company, and they suddently went out of business, taking with them all the expertise not only to build new planes but also all the expertise to repair, maintain, and service all the existing airplanes. In short, air-transport in the world would grind to a halt by 8am t. Yeah… THAT big.

So, why are Boeing and Airbus so big? After all, these companies are fairly new to the game — Boeing didn’t even get into commercial aviation until the jetliner days, and Airbus is a fairly recent amalgamation. What ever happened to venerable names, like Douglas, de Havilland, and Lockheed?

In short, they were victims of efficiency. Monopoly theory suggests that as firms become more-and-more efficient, the “also-rans” drop out. One big mistake and a firm ceases to exist. Think about automobiles — the U.S. alone used to have dozens of auto manufacturers. Today, we’re down to three domestic producers (not counting off-shore headquartered labels which are actually made here). Indeed, world-wide, the number of profitable auto makers may be just a hand-full after this recession is over.

It might surprise the lay person to read that financial services is actually a fairly low-profit business, compared to making automobiles or airplanes. Car makers can easily knock a few thousand dollars off the list price and still make money. Boeing is currently making millions of dollars in concessions on airplanes. On the other hand, margins on financial instruments are extraordinarly thin. If so, then how are the AIGs and Merrill Lynchs of the world able to pay seven- and eight-figure salaries? Simple — a one percent margin on a billion dollars worth of business is still $10 million.

In a world like that, where financial houses constantly trade with other financial houses, we end up with razor-thin margins, which leads inexorably to monopolies. Add to it the fact that these financial houses are massively intertwined, and we end up with houses of cards that could completely collapse if a major, key-stone player falls down.

How do we fix it? The first question is should we fix it? Is the cost of having to pick up all of Humpty-Dumpty’s pieces every few years greater than the cost of inefficiency? Of course, this question probably doesn’t matter, since the regulators in the U.S. and most everywhere else seem inexorably headed toward new rules which will add significant inefficiency to the process. Is that a bad thing? Probably not — it would be nice to go back to the day when there were 10,000 mortgage lenders in the U.S. rather than just a hand full, when there were dozens of major stock brokerage firms rather than just a few, and when AIG didn’t completely own the insurance business (and a few other businesses that may surprise you, like airplane leasing). The price of this — and let’s call it an insurance premium — will be significant inefficiencies in the financial marketplace.

4/21/09 — From a Seattle Perspective

Ironically, I’m writing this sitting in a hotel room in Baltimore.

As many of you know, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper is one of this year’s recession casualties. However, many of their staff, with much help from their loyal followers, have created a very good on-line news source for Seattle-ites. We wish it well, along with many more like it around the world.

My good friend, Chuck Wolfe, contributed an editorial today. Whether you’re from Seattle or not, I encourage you to read it here. His comments can be generalized to any community facing a changing development dynamic.

4/19/09 — Anyone Reading Krugman?

Some Nobel Prize winners do great things, then it gets misused. Options theory comes to mind — Fisher Black (who died before the Nobel was awarded) and Myron Scholes gave us some wonderful tools for understanding how complex instruments should be priced, but I doubt they ever predicted the wild-and-crazy derivatives market that would result from their elegant math.

Others do great things, then misuse their fame themselves. Case in point — Paul Krugman. Now, I personally agree with most of the rest of the economic world that Krugman’s work in international trade was brilliant. On the other hand, I disagree with a lot of his politics. Don’t get me wrong — I read him all the time, and encourage others to do so as well. Note the link to his New York Times blog over on the right hand side of this page.

None-the-less, his April 17, 2009 column, titled Green Shoots and Glimmers, is Krugman wearing his “glass is half empty” hat, which he loves so very much. His column stands on its own, and I encourage you to read it. I don’t disagree with his facts. What I disagree with are his interpretations.

I would concur that unemployment probably hasn’t hit bottom. My own touchstone, based on the Philadelphia FED’s latest survey, is that we’ll see unemployment bottom out sometime in early 2010 and somewhere shy of 10%. I think we’ve seen the stock market bottom, and I think we’re close to seeing the bottom on housing prices.

Krugman would say this is all bad news — signs that the economy isn’t recovering and the Obama administration isn’t spending enough money. I would counter that the best ANY administration can do is to arrest the downward spiral (which the administration has apparently done), clean up the mess (which they are doing), and get out of the economy’s way so the free markets can go back to work (which is precisely the opposite of what Krugman would have them to do).

Do I agree with everything Obama is doing? No, but he’s doing SOMETHING, and it appears, at least in the long telescope, to be working. I don’t think we should all be cheerleaders, and a good, loyal opposition is a healthy thing for a democracy. However, the biggest danger for Obama’s administration doesn’t come from the right, but from the left, as evidenced by Krugman’s column.

4/17/09 — GGP Files for Bankruptcy

Argus, on their blog, have a well-written report on the General Growth Properties Chapter 11 filing. I have more than a passing bit of interest in GGP — my Ph.D. dissertation was on REITs, and GGP was one of the companies I analyzed. More importantly, what implications does GGP’s filing have for retail real estate in general?

Is this a passing phenomenon, emblematic of the trough of a recession, or are we facing a structural shift in the American economy away from retail consumption? The former has some implications for GGP’s management (why did you leverage-up so much when you know that consumer recessions are cyclical realities?) as well as for their lenders and bondholders (why did you loan them so much?). The latter potentiality has much deeper, longer-term implications for both GGP as well as their competitors.

Only time will tell, but there is a lot of sentiment among both economists and other public policy types that a return to pre-2008 consumption patterns isn’t necessarily the best thing for America. Naturally, our global trading partners are apoplectic over such an idea — for example, if we quit “consuming” all of China’s stuff, many of their workers are either going to have to go back to farming or their economy is going to have to be more internally self sufficient. In either of those scenarios, China starts looking a lot like the next Japan, only much bigger.

4/16/09 –This USED to be weekly

A surprisingly large number of entrepreneurs are sitting on the sidelines waiting to see what the Fed’s toxic asset solution will look like. In the spirit of “deja vu all over again”, this look a heck of a lot like 1989/91, when the RTC was coming into existence and a significant number of private firms helped with the workout of bad assets from the Savings and Loan crisis. It was terrifically clear back then — and it’s clear to me now — that this was/is not the sort of thing that can be done internally at a Federal agency (then, the FDIC, now the Treasury). An agency simply doesn’t have the people-power or the entrepreneural expertise to put these assets back to work.

Fortunately, it appears that Geitner “gets it” and the early indications are that they will want to bring some serious players (the Blackstones, Blackrocks, and Goldman Sachs of the world) to the table. From there, it’s anyone’s guess, but my bet is a thousand small private equity firms will get involved to buy, repackage, and redeploy the bad assets.