Archive for January 20th, 2025

Some Thoughts on Housing Crisis

Last month, I had the very real pleasure of delivering a major, hour-long address at a conference in Charleston, South Carolina, on the nation’s housing crisis. In it, I discussed the overarching problem and some potential solutions, as well as some problematic ideas which are being bandied about. I’ll synopsize here today.

Right now, we have about 131.5 million households in America, a number which has been growing steadily almost without a break since WW-2. Right now, we ad about one and a quarter million households to that total each year. About two-thirds of us live in owner-occupied dwellings, a number which has remained constant for most of my lifetime.

Just focusing for a moment on the owner-occupied sector, median house prices have gone up about 317% since 1991. However, median household income has increased only about 167%. Over the past three decades, owner-occupied housing has only appeared to be affordable most of the time because (1) we had a sub-prime bubble with artificially easy money in the 1990’s, and then (2) we had very easy money – in fact, a liquidity flood — following the meltdown, and then (3) we have had extremely low interest rates until just a couple of years ago. Owner-occupied demand spiked during the recession, and as everyone knows, cheap money disappeared. Those of us with long memories recognized that today’s supposedly high interest rates were actually the norm a few decades ago. If the FED target of 2% inflation is achieved, it is still very hard to imagine mortgage interest rates coming down much below 5%.

In a reasonably efficient economy, home prices rising would stimulate homebuilders to flood the market with new product. However, a new home is the nexus of several different inputs – materials, skilled labor, land, and ‘soft costs’ (insurance, permits, mitigation fees, taxes, fees, etc.). Unfortunately, these inputs have all been problematic. Material, land, and soft costs have all risen rapidly, and skilled labor is in short supply. In many ways, builders are in worse shape than their customers.

In 2020, the Goldman Sachs housing affordability index stood at 135%, which meant that a median household had 135% of the income necessary to ‘afford’ payments on a typical 30-year conventional mortgage (with 20% down) on a median priced dwelling. Today that index stands at 70%. It is widely agreed that getting that index back up above 100% will be a herculean task.

By the way, what do we mean by ‘affordable’? In general, the total housing burden shouldn’t exceed 30% of a household’s take-home income. What do we mean by ‘housing burden’? For a homeowner, that includes payments on the mortgage (principal and interest), plus homeowner’s insurance and property taxes. Not only have mortgage interest rates soared in recent years, but also, we’ve seen insurance and property tax rates climb at above-inflation rates. While mortgage interest rates may come down in the near future, higher insurance and tax rates may be with us permanently. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that those will actually continue to significantly increase, particularly in hard-hit areas like California and Florida.

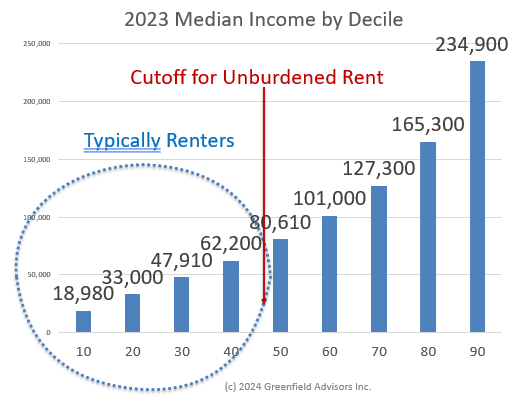

Amazingly, the rental community – about two-thirds of American households – have actually been hit worse. Note that as a general rule of thumb, renters come from the lower deciles of the income strata. Right now, the median household income in America sits at about $80,000 per year. However, the median income for the 40th percentile of Americans is only about $62,600. In other words – and this is a very rough approximation – about 40% of American households make less than about $62,200 per year. And remember, these households are more likely to be renters.

Right now, the median apartment rent in America is $1,595 per month. (The median rent on a single family detached dwelling is $2,000). Add to that about $300 per month for utilities and such, multiply by 12, divide by 30% (the threshold for ‘unburdened’ rent) and you get a household income of $75,800 per year to be considered ‘unburdened’ renting a median apartment in America. And remember, that’s a median, so fully half of the apartments in America are unaffordable for households making $75,800 per year.

Nobody in the bottom 40% of households makes that much money.

Indeed, an estimated 20 million households in America spend over 50% of their income on housing.

So how do we address these problems? We have two major sources of aid for low-income housing. First, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program provides indirect Federal support in the form of tax credits for developers of affordable housing. This program was created out of the 1986 Tax Reform Act, and until 2016 was responsible for building about 115,000 affordable units per year. However, since 2016, for a variety of reasons, the program has only helped finance about 75,000 units per year. As a result of this, in most of the country, we have fewer than 45 affordable and available units for every 100 low-income families, and in the hardest hit states, such as California, Florida, Virginia, and my home state of Washington, the number is under 30 units.

The other major source is the Section 8 voucher system. Funded by the Federal Government through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), but administered by local governments, this program provides full or partial rental vouchers for needy families earning less than 50% of local median income. However, the wait times for a voucher are awful (averaging 28 months nationwide) and only about one in four eligible households ever receive anything.

David Holt, the Republican Mayor of Oklahoma City, speaking on TV talk shows this weekend in his role with the national mayor’s association, noted widespread agreement among the country’s mayors that housing availability and affordability was their number one concern right now. So, what can we do to fix the problem.

Three ‘fixes’ come to mind immediately. First, a bipartisan group of both Senators and Congressional representatives have co-sponsored the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act (Senate bill 1557 and House Resolution 3238). This bill would fix some of the long-standing problems in the program and increase credits overall by 50%. However, the bill is currently stagnating in committee, and even though it has some powerful sponsors, it is simply not at the top of anyone’s agenda right now.

Second, some expansion of the Section 8 program is long overdue. However, the incoming administration is all in favor of massive belt-tightening. In the case of Section 8, this is woefully shortsighted, as the economic problems caused by unaffordable housing far outweigh the cost of this program. However, the attitudes on Capitol Hill are decidedly negative.

Finally, I would propose some significant overhaul in the HUD loan program (known back in my boyhood as ‘FHA Loans’). These loans provide Federal insurance – at no cost to the taxpayers – for homebuyers who meet stringent credit requirements. The loans carry extremely low down-payments – very close to zero. In the early 1980’s, when mortgage interest rates were soaring, many states were allowed to use tax exempt bonds to fund state housing finance programs which routed funds into HUD loans. This was a win-win for all concerned, and the economic stimulus of expanded housing construction far outweighed any lost revenue to the Federal coffers. However, the spread between tax-exempt and taxable bonds was somewhat greater back then, and so there was some meaningful leverage to be applied in lowering the mortgage interest rates, particularly for first-time buyers. That said, some kind of program like this, most likely using HUD leadership, would go a long way to breaking the logjam.

There are, unfortunately, some dumb ideas out there. First, a recent RAND study indicates that local governments, despite meaning well, have actually gotten in the way of affordable housing construction. The local restrictions are myriad, but as a result, the cost of building a new, affordable apartment in California, as an example, has risen to about $1 million per unit. This is utterly unsustainable.

Second, the incoming administration has posed the idea of building new homes on Federal land. Time and space will not permit me to list and discuss all of the reasons why this is a bad idea. As examples, however, it constitutes an intolerable wealth-transfer from existing homeowners to new homeowners, it runs afoul of the Federal mandate that any transfer of Federally owned land be at market value, and let’s face it, there is little available Federal land in any of the places where people actually want to live.

Finally, the incoming Administration has made it a priority to re-privatize Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These private sector groups, with the implicit guarantee of the full faith and credit of the US Treasury, are the primary secondary market makers for mortgage loans. During the housing meltdown, they were in effect ‘taken over’ by the U.S. Treasury, under the auspices of the Federal Housing Finance Authority, and now all of their considerable profits flow into the U.S. coffers. Both political parties have agreed that reprivatization is a goal, albeit for different reasons. However, the devil is in the details here, and a slap-dash reprivatization of organizations with combined balance sheets exceeding $4 TRILLION, would, in some estimation, add considerable burden to the current mortgage interest rates.

In the end, though, the real crisis is less about housing and more about affordability. In the owner-occupied sector, for example, house prices have been going up, on average about 2% above inflation year-after-year since WW-2. That’s really not a bad thing. It means that home ownership is a really good investment and a nearly perfect hedge against inflation. Even during the housing crisis following 2006-ish, while house prices dipped, they soon reverted to the mean, and today house prices are about where they would have been had the housing crisis never occurred. Over the same post-world war period, household incomes generally also trended upward, more or less, until the 1970’s. However, since then household income has simply failed to keep up with the cost of housing. In short, this current crisis has less to do with the cost of housing and more to do with the stagnating fortunes of middle-class Americans.

As always, if you have any comments or questions on this or any other real estate related topic, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., MAI